This series highlights working artists currently on staff at the Frye Art Museum. The Frye has a wealth of talented Seattle-based artists working under its roof in many different capacities, each with their own dedicated arts practice outside of their work at the museum. Normally facilitated and written by Alexis L. Silva, Curatorial Assistant, this series is meant to highlight and celebrate these individuals, showcasing their amazing work and arts practices.

By Rachel Townsend

Working Artists has crossed its one-year milestone! To celebrate all the hard work Alexis L. Silva, the Frye’s beloved Curatorial Assistant, has put into this series over the last year plus, our editorial committee decided to turn the tables and offer an interview with Alexis about their artistic practice.

When Alexis and I started talking about this interview, they bemoaned the fact that they’re so busy with their work at the Frye that they feel like they barely have an artistic practice these days. But don’t we all feel that way about things we love doing sometimes? Whether you created something last night or it’s been a year or two, or ten, since you made a work of art, your identity as an artist doesn’t leave you.

Plus, we’ve all experienced a taste of Alexis’s work through Working Artists! Photography is one of their primary mediums and they have shot the photographs for half of the series posts to date. So sit back and enjoy learning more about Alexis and their art!

Tell us a little about your background (although you’ve shared a fair amount about yourself over the course of the series—give us a refresher).

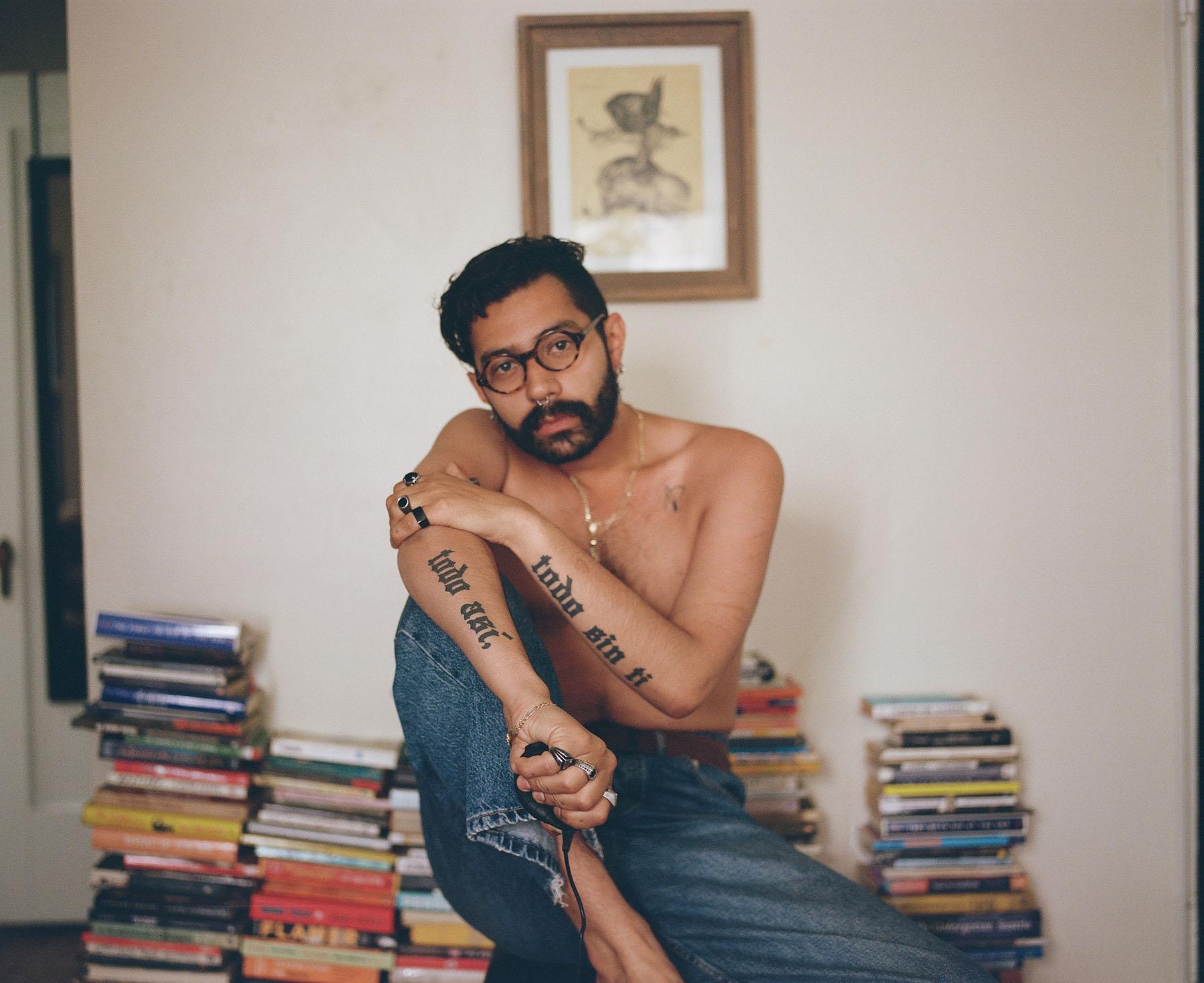

I am originally from the East Side of Las Vegas, NV; my parents are immigrants from El Salvador. I grew up in a low-income household where art wasn’t really seen as important. I was a pretty troubled kid, dealt with a lot of deep depression and anxiety at a very early age and got involved in some not so great stuff. I was bullied a lot for being queer and was not kind to myself because of it. I started to play around with photography and posting it on MySpace as an outlet for my anxiety and depression. Weirdly enough, my bullies and friends started recognizing my work on MySpace and I gained a bit of popularity. Nothing crazy! But it kept the bullies away, which I was thankful for.

I attended an arts high school in Las Vegas where I focused on photography. I started experimenting with performance and mixed media, and instantly fell in love. When it was time for deciding on colleges, I chose Cornish due to their “choose your own adventure” type of curriculum. During my time at Cornish, I was....an interesting student to say the least. Quite all over the place and, as some of my professors would say, “unreliable.” Some even went on to say, “you make things that look like art but aren’t really art.” There were probably two or three professors I felt I could actually trust and who believed in my practice.

One of those professors, Sharon Arnold, changed my life. She opened my eyes to so many opportunities and ways of thinking. I even have a quote that she said in one of our classes tattooed on my ribs. She is one of the main reasons I got into curatorial work. I really wanted to find ways to give back to the Seattle arts community by creating opportunities for folks who may be overlooked. I worked with Sharon for about two years and then went on to work at the amazing Wing Luke Museum for about three years. After that, I worked at Cornish for a very short time before I got hired here at the Frye!

How did you get started with photography? You have mentioned in interviews that you were enchanted by photography’s ability to capture time and the implications of that, rather than the technical aspects of photography at first; could you tell us more about that?

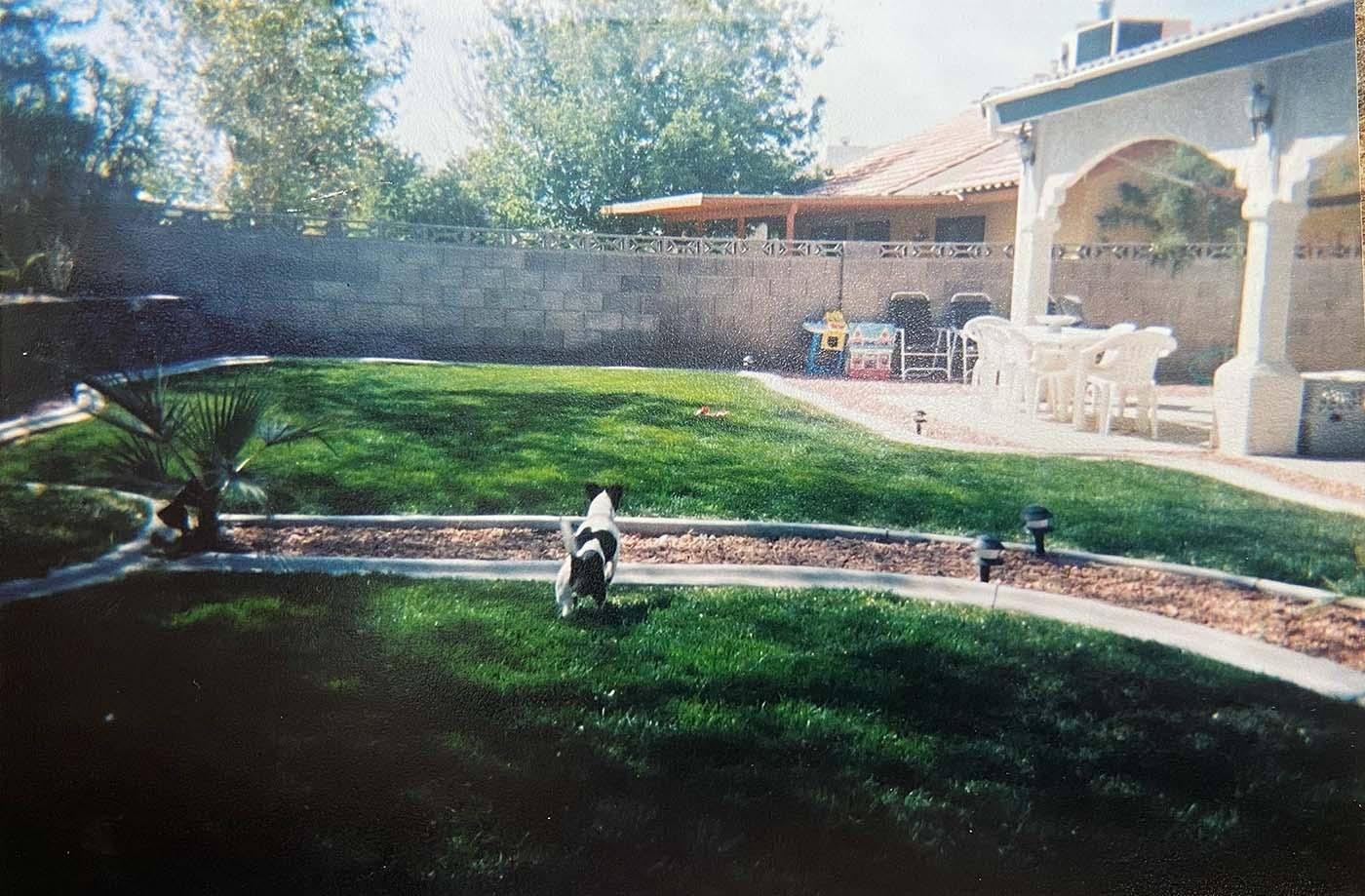

I always like to say that my “art journey” started when I was about nine years old. I was at the 99-cent store with my mom when I found a small plastic reusable camera in a bin of cheap toys. I begged my mom to get it for me and she was so reluctant, due to the cost of film. But finally, she said yes and got me a roll of film and it literally changed my life. I became fascinated with the idea of capturing time in a box: I would spend hours in the backyard trying to get a shot of my childhood dog jumping over this river of rocks. It was all just so fascinating to me.

I didn’t really think of photography as an art form or something with fundamental rules, I was just mesmerized by the action of taking a picture. It wasn’t until my pre-teens that I started to get more artistic with the medium. And by artistic, I mean I learned how to turn my photos grayscale and used way too many Myspace digital stickers. Once I learned the more technical side of photography, I realized I wasn’t interested in following the rules. I was more concerned with capturing moments that meant something to me or made me feel something. I’ve always been prone to using myself as a subject in my work, using my body as a sort of tool or mirror for the viewer to find themselves in. To this day, I am not really concerned with technical photographic rules, and I like it that way.

How did your practice expand and develop to include performance and installation work?

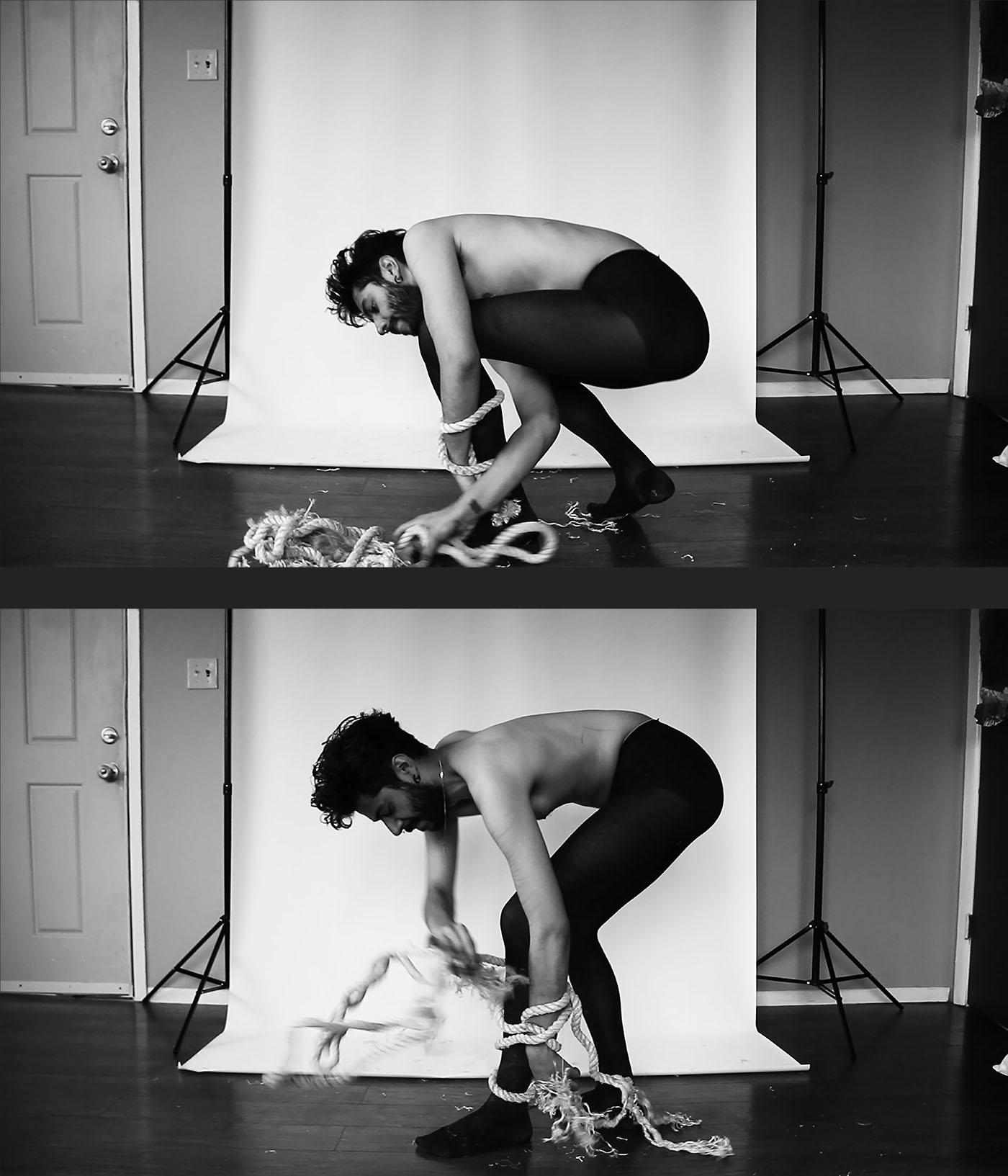

I really dove into installation and performance my first year at Cornish. I became interested in how you can use your body as a medium and how the body interacts with space/architecture. I also started to think about the body as architecture. I became interested in sculptural performance at first and then incorporated endurance performance. I really enjoyed audience participatory performance as well, I think it really makes folks cross a line that they wouldn’t otherwise. I once did a performance where I allowed people to make a mark on my body only using their mouths, it was quite wild.

Performance work is really about framework and building a space where an audience engages with your body in a way that they wouldn’t in a “normal” context. You have to challenge your mental and emotional state in performance, almost becoming blank. It’s extremely exhausting and takes so much out of you. My interest in installation came from this fascination with the poetics of architecture and space. I really enjoyed this act of manipulating space with materials and objects to explore different conceptual narratives, or to create immersive experiences. I loved finding materials I had never worked with and seeing how they acted in space. I always found that part of my practice to be laborious and experimental, trying new things and hoping to pull something out from it.

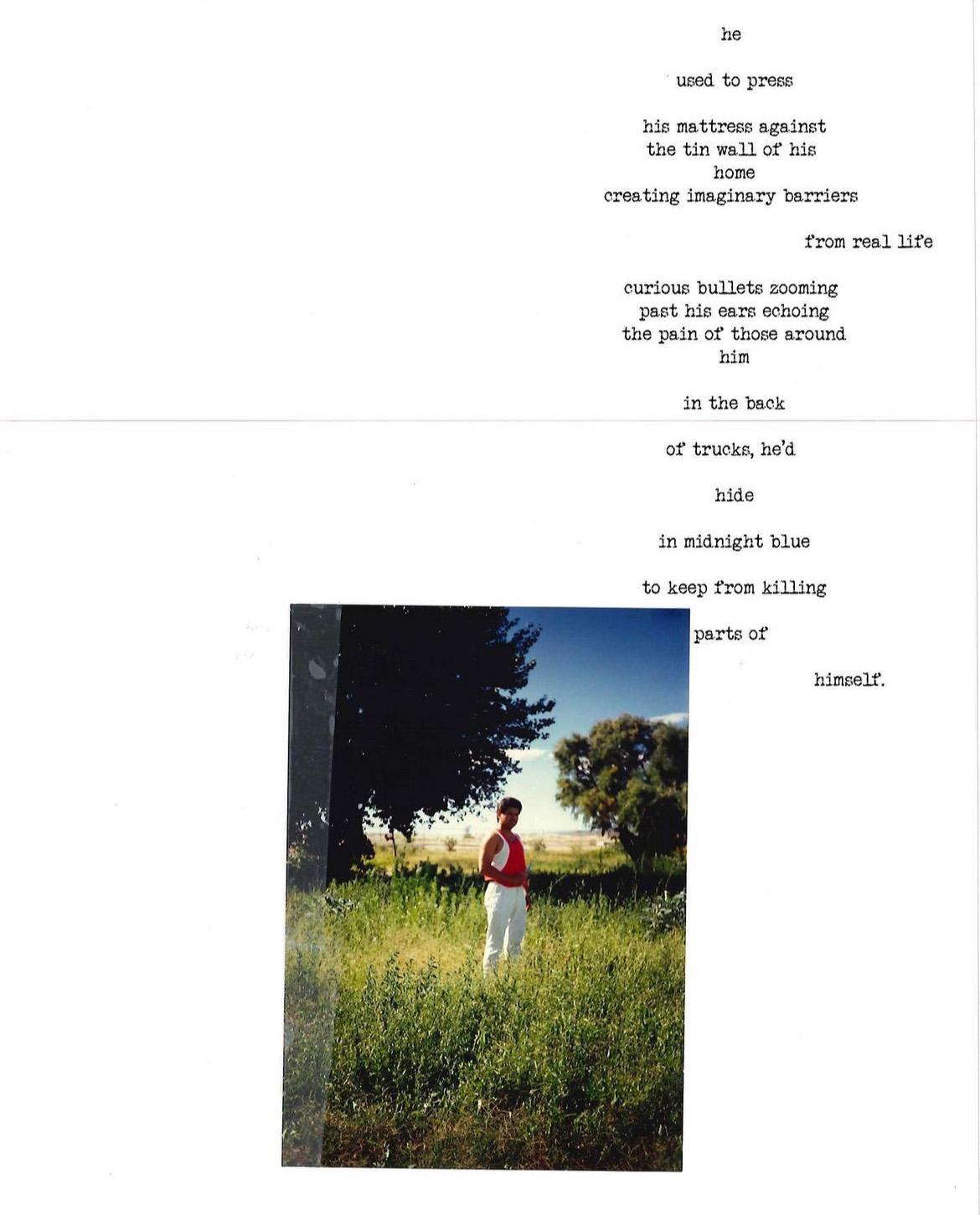

Talk to us about your piece Como Nos Dejaron: what led you to start exploring your family’s stories and history in your work?

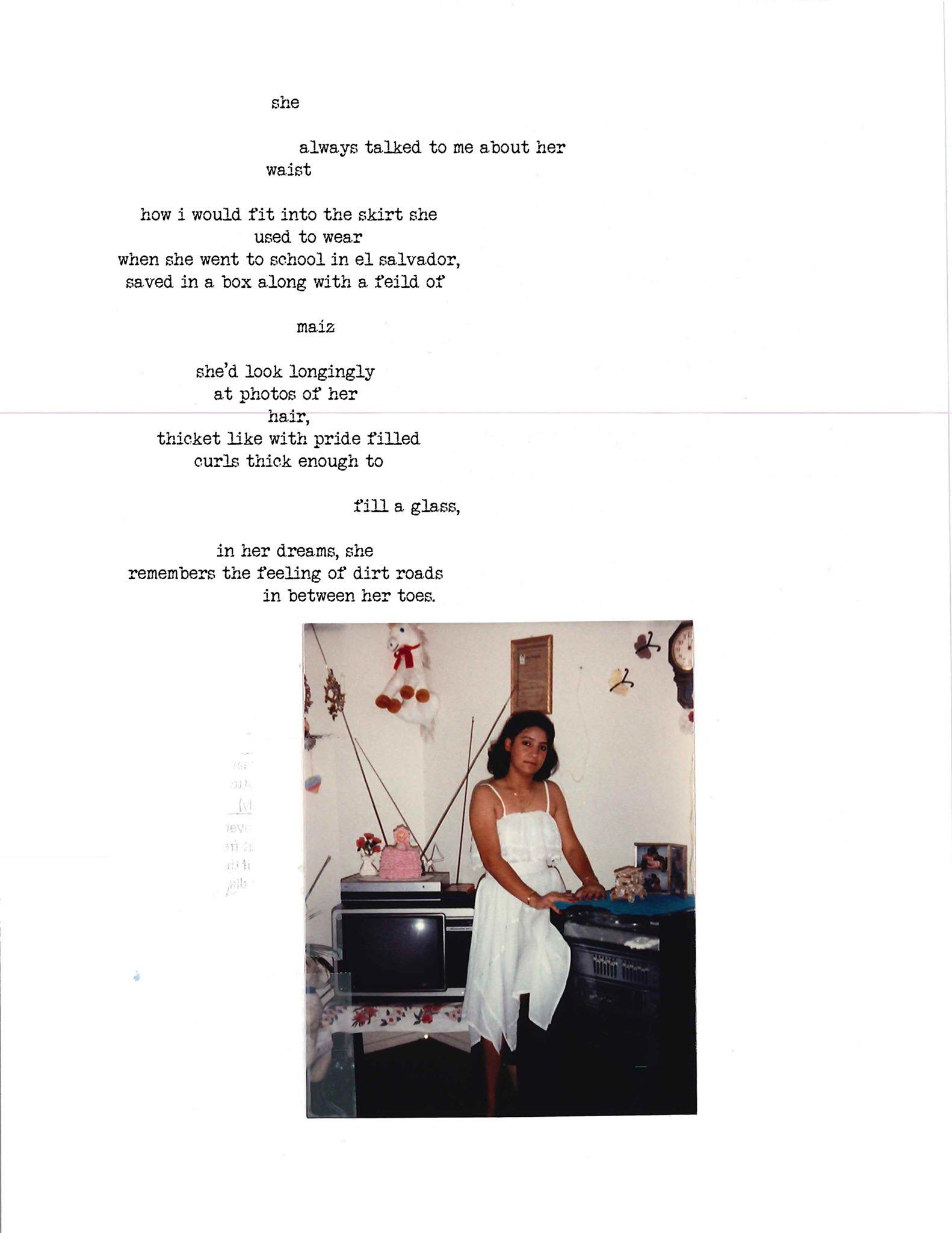

As a child growing up in an immigrant family, I found myself really trying to assimilate and not being interested in family traditions/stories. I almost felt like I lived in this weird bubble where no one understood me, and I wanted out so badly. After I moved to Seattle and got a bit older, I started to appreciate my family’s sacrifice and their resilience, their ability to set goals and to make a new life in a whole new world. I started a series in which I would write a poem for a family member and then incorporate a found image of them. It was born after listening in on conversations my family members had over wine. It was the first time I had felt seen as an adult and felt such a strong appreciation for my family's story.

I wanted to honor them with this series which then grew to Como Nos Dejaron. That piece was really commenting on the aftermath of US involvement during the Salvadorean Civil War. Many of my family members felt the hit of that war—my father was drafted at 12 years old. He fled the country and was deemed a deserter and wasn’t allowed to return for many, many years. It was stories like these that really got me interested in highlighting my family’s stories as Salvadorean immigrants.

Not to mix your art practice and work duties at the Frye, but you’ve talked pretty openly about how you feel that curating is intertwined with artmaking for you. Can you tell us a little more about that?

When you think about it, curating and artmaking are really about storytelling. It’s about creating a narrative inside of a space. Whether that space is architectural or inside a canvas, you are creating a story for an audience to latch onto.

As an artist, my job is to transcribe meaning and ideas into a body of work to create a narrative. As a curator, my job is to interpret this narrative and connect conceptual threads to create a larger narrative in a space. I love being able to work closely with an artist to really understand their vision and practice. It’s kind of a push and pull, and you have to have a balance to it all. But all in all, it’s really about collaboration and working towards creating a happily married conceptual narrative.

Tell us about your vision for the future of the Seattle arts community. Do you feel like a project like Working Artists has a role to play in that vision?

I have sort of been dreading this question even though I ask it to everyone. I echo many of the folks I have spoken to doing this series in that we need more art spaces for BIPOC creatives in our region. We need more BIPOC led art spaces. We also need to see more BIPOC folks on staff at our city's art institutions. Getting to where I am today was not easy; for a while, I did not feel welcomed in this community. I didn’t see myself reflected, and that was extremely hard to navigate.

We need to expand beyond a select group of individuals and show the upcoming emerging creative professionals that it is possible to navigate this community. We need to be more welcoming, I think. We are slowly getting there, but we are not there yet. I really do hope that this project is helping by shining a light on the many talented individuals that we have not only on staff here at the Frye, but in the city. I hope that the series helps get folks opportunities and opens the eyes of readers who are a part of the art ecosystem in Seattle.

Where can people find you?

People can find me on Instagram @brujapapi