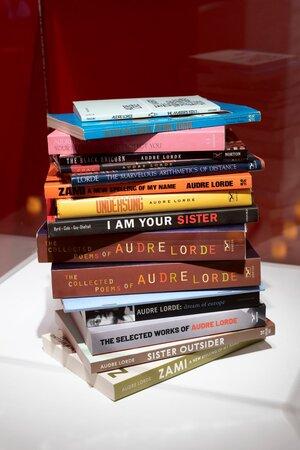

When I asked Anastacia-Reneé to tell me about Alice’s Sanctuary for the Lorde, a devotional space within her exhibition (Don’t Be Absurd) Alice in Parts, the first thing she did was send a reading list of works by Audre Lorde:

The Master’s Tools Will Never Dismantle the Master’s House

Sister Outsider: Essays and Speeches by Audre Lorde

Black Unicorn

The Marvelous Arithmetics of Distance

Zami: A New Spelling of My Name

I Am Your Sister: Collected and Unpublished Writings of Audre Lorde

The Collected Poems of Audre Lorde

Audre Lorde: Dream of Europe

The Selected Works of Audre Lorde, edited by Roxanne Gay

Need: A Chorale for Black Women Voice

I recognized a number of the titles from the stack of books included in the installation and thought I understood—these were some of her favorite selections of Audre Lorde’s writings. Lorde was a prolific writer and activist who described herself as “a Black, lesbian, mother, warrior, poet.” Her work dedicated to social and racial justice was central to many movements, including second-wave feminism, civil rights and Black cultural movements, and struggles for LGBTQI equality. Lorde continued steadfast in her practice following her diagnosis of breast cancer in 1978, an aspect of her life that became integral to her writing through her death in 1992. When Audre Lorde’s birthday came around on February 18, Anastacia-Reneé sent the list again, and I noticed the image of the stack of books from the exhibition was part of her email signature. I realized then I should be thinking of this list as something more than a simple collection of favorites.

That Anastacia-Reneé’s suggestions were carefully made wasn’t surprising. She is a widely published writer, playwright, and interdisciplinary artist. Much aligned with Audre Lorde’s practice, her work is rooted in the Black feminist and womanist traditions and their intersectional approach to addressing racism, sexism, homophobia, ageism, and class.

Anastacia-Reneé. Alice in Parts (video still), 2016. Digital video (black and white, sound); 30:36 min. Courtesy of the artist

So, I asked what the Sanctuary for the Lorde means to Alice Metropolis, the character Anastacia-Reneé created through her writings and performances and whose home we are invited to experience as visitors to the exhibition. (Don’t be Absurd) Alice in Parts centers on Alice’s struggles against various forms of gentrification, some of them literal, as in her displacement from her home and neighborhood, and some figurative, such as the colonization of her mind by the anxiety of navigating white supremacy every day. Alice also had breast cancer and turned to Lorde as an inspirational figure who continued living her life fully through her illness. “Alice needed a dedicated space—a sanctuary for the Lorde, if you will, where she could go and worship,” Anastacia-Reneé explained. “And, by worship for Alice, that just simply means communing [with] Audre Lorde, thinking of Audre Lorde as an ancestor, or as this energy and source that will help her through some of the things she’s going through.”

Installation view of Anastacia-Reneé: (Don’t be Absurd) Alice in Parts, Frye Art Museum, Seattle, January 30–April 25, 2021. Photo: Jueqian Fang

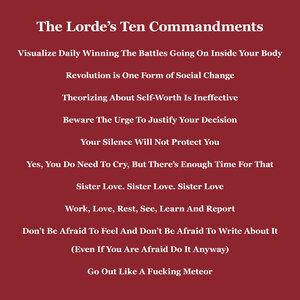

In Alice’s Sanctuary for the Lorde, a large black ankh presides over an altar filled with an array of objects. Orisha candles flicker. Garments dyed in rich yellows and blues are draped over the altar’s surfaces. Alice’s anxiety-ridden monologues that echo through the rest of the galleries—keep it moving, keep it moving— recess. Three video montages show Audre Lorde from throughout her career, including readings in Berlin during the final years of her life. A panel inscribed with The Lorde’s Ten Commandments anchors the display. And, the stack of books gleams as an objet d’art in its own right from an adjacent pedestal.

When I inquired about how the altar came together, she told me, “Audre Lorde traveled a lot, and she was always picking up things that she deemed spiritual. So, a lot of those objects are me, Anastacia, saying, ‘What would Audre like? I think she would like this head wrap. I think she would like his gown...’” It was clear how meticulous Anastacia-Reneé had been in her selections as she considered imagery from the videos in the display, as well as her deep knowledge of Lorde’s life and writings.

That intimate knowledge also informed The Lorde’s Ten Commandments, a document Anastacia-Reneé said she agonized over and could have easily been much longer. “I went through eight or ten of Audre Lorde’s books and created the list of commandments for Alice,” she said. “Alice needed something tangible—something she looked at every day and say to herself, ‘Okay: go out like a fucking meteor. Am I going to die today? No. I’m going to do these things.’”

In her introduction to The Selected Works of Audre Lorde, writer Roxanne Gay discusses an open letter that Lorde wrote to the white feminist Mary Daly: “’Did you ever read my words, or did you merely finger through them for quotations which you thought might valuably support an already conceived idea concerning some old and distorted connection between us? This is not a rhetorical question.’” Gay goes on to explain, “In the thirty years since Lorde wrote that open letter, Black women have continued to implore white women to recognize and engage with their intellectual contributions and the material realities of their lives.”

In this context, I realized that I—myself a white woman—should be asking not only what the Sanctuary for the Lorde means to Alice Metropolis or to Anastacia-Reneé, but also what it can mean to me. That I should consider The Lorde’s Ten Commandments and Alice’s Sanctuary for the Lorde not as ends to be grasped but as evocative starting points. That I should get to work on the reading list, but that it, too, is only the beginning of understanding the breath of Audre Lorde’s work—and of Anastacia-Reneé’s work, too.

Erin Langner

Exhibitions & Publications Coordinator