Seattle-based interdisciplinary artist Laura Hart Newlon’s A prop, grip or hold (2023) is on view at the Frye as part of the Boren Banner Series through October 1, 2023. In this interview with Frye Associate Curator Georgia Erger, she reflects on found images, the labor and construction of photography, and her recent film work.

You work with an ongoing, wonderfully idiosyncratic archive of found images. Where do you source these images from and what are you generally looking for?

I’ve always been drawn to what you could think of as ‘how-to’ or instructional photography. These are photographs that are made generally without much regard to aesthetics and composition, and for a very specific purpose and context: instructing the viewer on something in a straightforward way. But when you strip this context away, I think they become magical and fascinating. All of a sudden, it’s like they’re this unanchored floating signifier, not quite attached to any particular idea or place or person. At that point, they’re so malleable and that possibility is exciting to me – all the ways you can build associations between different constellations of seemingly unrelated photographs. This isn’t a new way of working (thanks to some of my favs, Larry Sultan and Carmen Winant), but there’s endless discovery in it, given the number of images we’re exposed to daily. I have an ever-growing digital archive of images I pull from the web, anything from advertisements to stills from instructional videos. I’m also amassing a collection of used books in my studio, a kind of chaos garden repository of found stuff. My latest find is a trampolining manual from one of those sidewalk neighborhood libraries—it’s fantastic! Over the past two years, I’ve been interested in photographs that somehow show a force playing out on or through a body, generally working with femme-reading bodies—turns out there’s some pretty weird stuff out there! I tend to favor half-tone photographs scanned from physical books, both because of their mass media history and their ability to be reproduced and scaled so beautifully, which can be a challenge with digital photos.

As a follow up, can you offer insight into the found images included in your Boren Banner artwork A prop, grip or hold and the choices you made around their composition and cropping?

All of the photographs I used in the banner come from different sources but in some way show the interaction of two or more bodies. I was most interested in the point of contact, the gesture where we can attempt to read little clues about the ambiguous nature of the interaction —is it tender, is it aggressive or violent, are the bodies supporting or repelling each other? Isolating that moment was important to me, while cropping out any superfluous information about the individuals or context or original intent of the photograph. Given that, however, I cut them out without a lot of interest in precision or anything surgical—I let the gesture itself determine the overall shape of the cutout, and the irregular curves remind me of how my kindergartner cuts out things for projects. They also remind me of the shape of bodies.

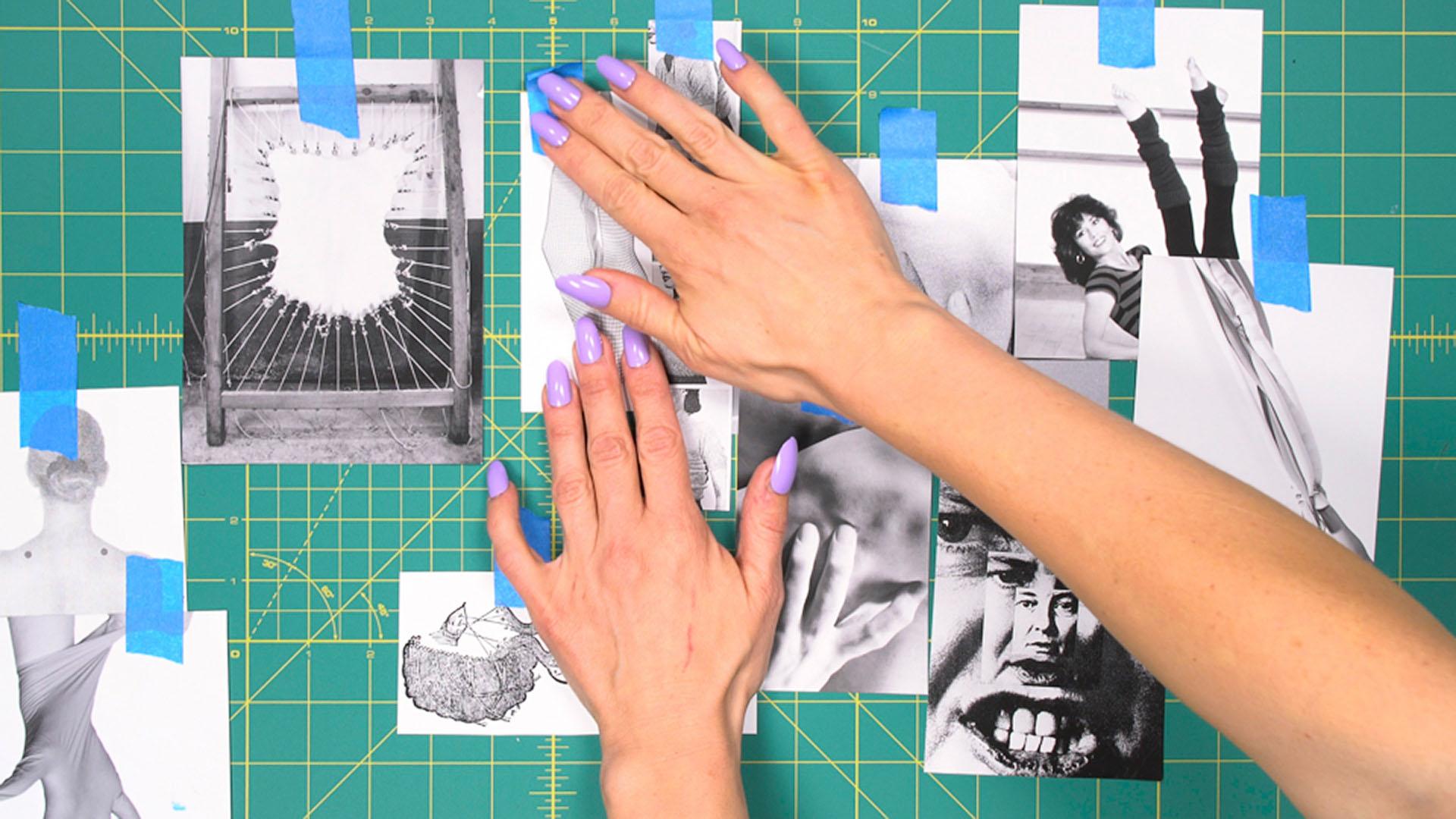

The labor of image-making is explored across your work; we see this in A prop, grip or hold, for example, in the way the hands gently tend to the collaged images. Why is it important to make complex photography processes and the care of the artist visible?

I draw a lot of parallels between labor and caregiving or caretaking, and nowhere is this dynamic more apparent to me than in my life as a parent and my life as an artist. Similar to the types of gestures I’m interested in, these forms of labor are not "neutral," though they can often be invisible– there is both tenderness/anger, joy/frustration, gentleness/aggression that are embedded within them. I think I’ve personally grown a little tired of the slick façade we’re often presented with in a photograph (though that idea itself is interesting!), and I want to be more transparent with the messiness of it. Revealing the making itself, making it visible, is maybe a way of giving the photographs I make some kind of history, a provenance—but it’s also a way of acknowledging that hands, a body, and care/labor created this thing in the world. Historically, we don’t often recognize the ‘artist’s hand’ in photography, and I think I like the idea of revealing this deliberately (and sometimes literally). Photographs are constructed things, with the ability to be de- and reconstructed again and again!

Photography is often understood (or perhaps misunderstood) to offer a transparent or “truthful” view of the world, but the artist makes so many interventions in what and how we see. Can you describe the ways in which you work fluidly between analogue and digital photographic processes to “construct” images?

Sure—I think this speaks to some of my thoughts from previous questions. So, take a photograph of a young girl in mid-flight from a trampolining manual, for example. In its original form, in the book, the image is intended to teach you about how to maintain proper form in a tuck (okay, truthfully I know nothing about competitive trampolining!). When I use it, however, that isolated gesture becomes more about the precarity or awkwardness of a body pulled in tight when it’s in freefall, or the careful, guiding hand of the coach who is helping the body, though it’s unclear exactly how. All of a sudden, what we know about the photograph completely changes, though the image is the same. Sure, photographs certainly can communicate transparently—but they can also be shifty and unstable, and I’m more interested in that, which is also "true."

I think using both analog and digital tools together helps me to lean more into the instability of photography. For instance, the trampoline image is an analog photograph reproduced as a halftone image in a book, then scanned (itself a photographic process) by me to create a digital image, which is later printed and becomes another physical object in the world. These are all tools photographers use practically in a contemporary practice, but they also offer us opportunities to intervene and experiment and get a little messy. I suppose this goes back to my interest in having some of my work make visible the labor behind it.

The act of looking is especially complex when the subject is femininity. Many scholars have addressed the historically enacted assumption that men actively look and women are objects to be looked at. For example, film theorist Laura Mulvey states that “the determining male gaze projects its fantasy onto the female figure, which is styled accordingly.” How do you address the conflicting intimacy, pleasure, and violence of picturing the female body across your work?

One of the interesting aspects of working with found images is how absolutely obvious it becomes that the female or femme body has historically operated as this seemingly blank canvas onto which mass culture can project its hopes, fears, desires, and fantasies. It’s not an accident that most instructional photography I find features women, or even body parts—a hand, often—that reads as stereotypically feminine. And, what’s been culturally considered a blank canvas is anything but – it’s a white, young, cis/het woman (Shirley cards are such a great example of this in Kodak’s history!). I think that by isolating, recombining and recontextualizing these images, both the explicit and implied violence of that gaze becomes more apparent—it shows up in ways that we might not immediately anticipate. But I’m also interested in the way both visibility and invisibility can operate as tools to be deployed. Choosing when and where and how to be seen is powerful in the world, and I think this agency is also at the heart of why I gravitate toward recycling found images and working with collage strategies. Looking can play out forcefully, aggressively, or gently on a body—I think there is a physical, material effect, not just a psychological one. But looking itself is also an embodied practice, and I try to anchor it there in my work.

You’ve recently started working in film. Your incredible work Heavy Focus also features hands, here layering and taping photo prints on a gridded cutting mat. What possibilities does the medium of film offer you in further exploring ideas and techniques you’ve been developing in your photographic practice?

Heavy Focus was something that lived in my head for a long time and gradually came into being through ping-ponging between writing, research, and found photo collecting. It was genuinely fun to see how the writing influenced how I brought different images together and vice versa. I’m in the midst of working on another video piece right now that incorporates sound, and it’s exciting to think about the labor and mechanics of filmmaking as fodder for the piece itself. A lot of my work involves staging for the camera, and the setup for that can be elaborate at times, maybe with video work in particular. Moving images have duration, which becomes this awesome tool to communicate the process of coming together/breaking apart, arranging/re-arranging, or toy with the expectation that ‘something’ is going to happen. Working with sound adds this sculptural dimension to video that I’m having fun exploring, and also is another way to create what I hope is a more embodied looking experience. This way of making work is pretty new, but it’s super fascinating and I’m learning so much.