Duane Linklater. What Then Remainz, 2016/2021. Disassembled wall(s), powder-coated steel, steel screws. Dimensions variable. Courtesy of the artist. Installation view from Duane Linklater: mymothersside, Frye Art Museum, Seattle, 2021. Photo: Jueqian Fang

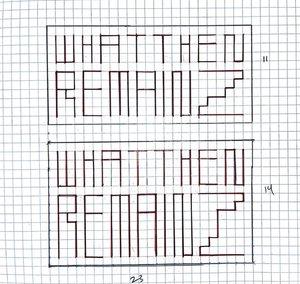

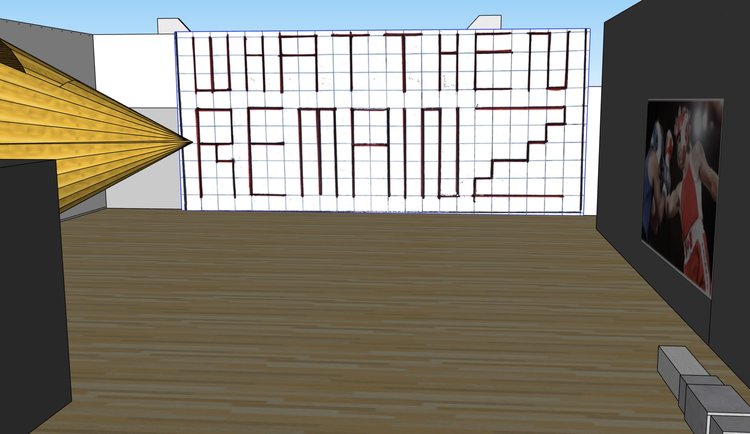

What does it take to tear down a wall? The question is an apt metaphor to consider in the context of the Museum’s exhibition Duane Linklater: mymothersside. Working across a range of mediums, Linklater’s artistic gestures serve to open the museum—a historically exclusionary construct—to Indigenous content. However, the question of how to tear down a wall also became a literal one I had upon walking into one of the Frye’s galleries and experiencing Linklater’s massive, site-specific What Then Remainz (2016/2021). Following the artist’s directives and design for this work, museum staff had stripped an entire gallery wall down to the metal framework and added studs that had been powder coated in red to spell out the towering set of words that comprise the installation’s title.

Taking down a wall in a museum is far from a straightforward task; the integrity of the building, as well as the safety of the people and objects inside of it meant that there were many factors to consider. Although Linklater had created What Then Remainz in other locations beginning in 2016, the specifics of each site mean that the work of art must be configured differently every time it is installed. Before any physical labor even began, the artist and museum staff had to determine the best wall of the Frye to take apart. “Locating the piece was difficult because we really wanted to give it a wall where it would have nice, wide-open sightlines and the presence would be really big,” says Shane Montgomery, the museum’s Manager of Exhibition Design and Production.

Initially considering a gallery wall that ran along the museum’s perimeter, the staff had to explore the consequences of eliminating some of the building’s insulation. “We found that removing that particular wall could really mess with the climate conditions of the building—it could throw off HVAC and we could have condensation developing on the wall’s interior,” Montgomery said. Climate control is a particularly important consideration in relation to the conservation and care of other objects in the museum.

CAD rendering of What Then Remainz used by the Exhibition Design and Production team

The installation team also didn’t know what they would find once the wall’s sheathing was removed; this meant they were not able to create architectural drawings of the elevations of the interior spaces within the walls that are central to the artwork. So, the team punched strategic holes into the drywall, to see what was inside. As they began testing a second, interior wall for What Then Remainz, they were met with many surprises. “We found our building system's structures and conduit and supporting systems were all anchored to the wall frame system that would be used to create the artwork,” Montgomery says. “We also found an old Diet Coke can that had probably been in there since the 1990s.” After discovering those systems, the Museum worked with Linklater to configure the design in ways that kept them intact without compromising the impact of What Then Remainz.

In order to create the red lettering that spells the work’s title—a reference to a 2016 US Supreme Court ruling on the jurisdiction of tribal nations—the metal wall frame also had to be specially powder coated. This involved preparing the frame to match Linklater’s design, with museum staff meticulously taping it off with aluminum foil before sending it to an outside vendor, who would complete the powder coating. “That was, by far to me, the hardest part—getting that tape into every little nook and cranny and then sealing it, so you don't have bleeding,” explains Ken Kelly, Lead Exhibition Preparator. “And all while staying coordinated, because we had five or six people working simultaneously in teams, and we were working on short, horizontal sections that connect to form the letters.” After the powder coating was completed, the studs were returned to the museum to be installed to striking affect—one that is both radically deconstructed and yet maintains a sheen of grace and ease as the wall stands positioned in the gallery, among Linklater’s other works.

Preparing the wall frame for powder coating. Photo: Dan Gurney

Every exhibition involves significant labor that occurs mostly unseen by visitors. As Kelly says, “In our jobs, there are tons of first encounters. In this case, I had never really had experience with powder coating, much less, this particular kind of project… It was pretty fascinating.” While the intangible resonance of What Then Remainz will continue on in the minds of visitors who experience it, the piece will also physically remain in place. At the end of the exhibition, drywall will be applied over the powder-coated studs, leaving them to live on inside the gallery indefinitely—an action that raises poignant questions about how works become part of a museum’s collection, or in this case, part of the museum itself. “An unusual part of this process was we built something permanent for the museum that no one is going to see after the show is over, which is a very different situation for us, as preparators and installers” says Montgomery. “In some ways, it feels strange and disappointing, and in other ways it feels beautiful and significant.”

Erin Langner

Exhibitions & Publications Coordinator