For Omaskêko Cree artist Duane Linklater, music is integral to his sense of memory and identity. The artist’s relationship with particular songs and performers forms a backdrop not only to his work in the studio but to everyday personal experiences, like exercising, driving, and hanging out at home with his family. In addition, music plays an important role in Linklater’s participation in Omaskêko Cree cultural and spiritual life. Not surprisingly, visitors walking through the exhibition Duane Linklater: mymothersside might even recognize a song title or two.

Central to Linklater’s work is the question of individual and collective identity. Music is just one way in which he’s played with the ideas of loss, forms of expression, and meaning-making. In 2017, Linklater’s exhibition apparatus for the circulation of Indigenous voices and ideas into the air opened at Western Front, non-profit artist-run center in Vancouver, BC. Inspired by Wawatay Radio’s focus on providing listeners with access to the Indigenous languages of the Treaty 9 area over the years, Linklater sought to create a way to disseminate ideas, stories, and music. For the exhibition at Western Front, he installed a small AM radio station that he had been broadcasting from his home in North Bay, Ontario. The artist offered this radio apparatus as a space for the Indigenous community of Vancouver to use freely and to broadcast their own songs, ideas, voices, poems, complaints, grievances, ramblings, and more on the radio in the gallery space for the duration of the exhibition. In conjunction with that exhibition, Linklater also launched Ehepick Records, a label that releases work made by Indigenous artists.

Given this musical affinity, the Frye asked Linklater to share a playlist in conjunction with the exhibition. Linklater put together this collection of songs while training for a half marathon. We hope you enjoy it.

When visiting mymothersside, either in-person or virtually, you can learn more about Linklater’s artistic connection to music through these works:

winter in america_no door_âkamenimok (2020)

The artist made the hand-drawn hashmarks on the work’s surface during the early stages of the COVID-19 pandemic lockdown and amid Black Lives Matter protests for racial justice, reflecting on the passing of time, the cyclical nature of social history, and the notion of the whole comprising the many. The title refers to the influential Black American jazz poet Gil Scott-Heron’s 1975 song “Winter in America,” which describes a dystopic American society of “last-ditch racists marching across the floor.”

Each component of this installation is the same size and shape as a functional tepee cover, complete with stake loops and rectangular smoke flaps. In Cree tradition, tepee covers would typically be made of animal skins or sturdy cotton duck canvas, but Linklater uses hand-dyed linen as his support for digitally printed imagery and charcoal markings.

can the circle be unbroken 1-5 (2019)

The title of this set of five tepee-cover paintings is borrowed from a song released by the Carter Family in 1935, which tells of the death and mourning of a beloved mother from the perspective of one of her children. Linklater created the installation following the passing of his mom, Pauline Linklater, but the work also speaks to loss on the broader scale of collective history. The floral designs printed on the joined linen components are sampled from the paintings of Dutch artist Ambrosius Bosschaert the elder (1573–1621), whose work inspired the patterning of fabrics that the English traded with Cree peoples beginning in the seventeenth century. Over time, these kinds of European floral patterns largely supplanted the Cree peoples’ customary geometric designs in beading and other crafts, effectively breaking an aesthetic ancestral lineage. Linklater dyed and smudged the printed linen with plant matter and earth minerals native to the region around his home in northeastern Ontario.

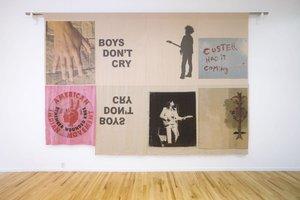

boys don’t cry (2017)

A portrait of the artist’s hand in the upper left is the only original element among the appropriated images, insignia, and text composing this work. Three of the central panels refer to The Cure’s 1980 album, from which Linklater borrowed the work’s title, including the iconic silhouetted image of front man Robert Smith that appeared on related promotional posters, stickers, and T-shirts. The other panels picture Jesse Ed Davis, an Indigenous guitarist who played with the band Taj Mahal, among other acts; the logo of the American Indian Movement (AIM), dyed pink; a photograph of graffiti from Alcatraz Island, where AIM activists famously protested for nineteen months between 1969 and 1971; and, sewn in sideways, George Caleb Bingham’s 1845 painting Fur Traders Descending the Missouri, from the collection of the Metropolitan Museum of Art. Individually, these images all have personal resonance for Linklater and recall significant periods in his life; together, they reflect on processes of identity formation and the construction of Indigenous masculinity.

primaryuse (2020)

Linklater and his son Tobias make music together through their project eagles with eyes closed. You can hear some of their work in the exhibition—they created the soundtrack to the artist’s video triptych primaryuse.