Seattle-born, Portland-based photographer Sadie Wechsler’s Between the Tideflats and the Lake (2021) is currently on view on the Frye’s façade as part of the Boren Banner Series. This new, billboard-size work is inspired by the ecological history of the First Hill neighborhood. The image is based on the artist’s research into plant communities that were present on First Hill around 1850—the period preceding the arrival of white settlers and the ensuing transformation of the land through logging, leveling, infilling, and urban development.

In the conversation that follows, the artist speaks with Frye staffer Erin Langner about her work and her process for creating Between the Tideflats and the Lake.

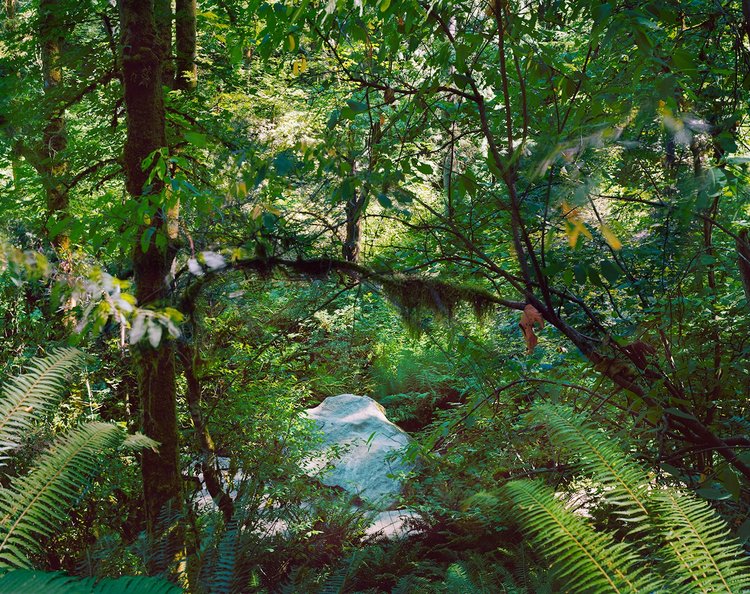

Sadie Wechsler. Between the Tideflats and the Lake, 2021. Digital photograph on vinyl. 16 x 20 ft. Courtesy of the artist. Installation view from Boren Banner Series: Sadie Wechsler, Frye Art Museum. Photo: Jueqian Fang

Erin Langner: As someone who grew up in Seattle and then moved to the east coast to pursue your undergraduate degree and MFA, what was it like to return to this area to photograph its landscape for the banner project?

Sadie Wechsler: That's a good question. I was raised between Seattle’s Capitol Hill and Montlake neighborhoods. During my time on the east coast and now living in Portland, I think I've come back and forth quite a lot. In that process, I have found myself watching Seattle shift so much—I always feel like I’m relearning a place through the exponential transformation of the built environment that's taking place during my lifetime.

When the Frye’s former Associate Curator David Strand approached me about the project last winter, I was immediately drawn to the museum’s location, in terms of both its past and its future. So, on top of the learning I was already doing around plant identification at that time, I started doing research remotely about the city of Seattle and its transformation beginning around 1850—a date not that long ago, when settlers arrived. I really immersed myself in learning about the shift of the landscape, often through becoming more informed about the original hills and waterways.

Then, when I was finally able to come back to Seattle in-person for the first time last spring...it was really wild. I felt like I was re-experiencing the place where I grew up—even my parents' house, which is surrounded by trees and parks. It was like, all of a sudden I knew about each tree’s heritage, and I could identify the native and horticultural plants. My knowledge about the area had grown so drastically, allowing a very altered perspective.

It was also exciting to differentiate this newer knowledge from my previous knowledge, which had really been rooted in my lived experience. I had found myself clinging to the Seattle of the 1990s as my conception of my “true” city. Instead, I’m now reorienting my thinking to move away from “city” to the broader concept of “habitat”; this location is much older and wiser than the new, shifting city that sits on top of it.

EL: What is the role of the archive in your process as an artist? I noticed some of your earlier projects like The American War draw upon archival research and documents.

SW: During undergrad, I studied with the artist An-My Lê, and her work often involves getting inside of institutions—or inside of the military, specifically—and obtaining access. I also worked with some other artists whose processes centered on accessing locations that aren't available to public, or on ways of interacting with locations that aren't “open” on the surface-level, like people’s homes. So, the pursuit of access has been very much part of my practice, and that process has often led to a lot of research. Earlier in my career, I photographed dams, which led to working with the Department of Reclamation and the Army Corps of Engineers in order to take those images. And in the early 2000s I was photographing fires and working with the constraints of access from that angle.

The archive element is newer, though, and I think really what happened was a switch from general research to focusing more specifically on a place. This began when I was doing work in Laos related to The American War. I spent a lot of time going into museums and places that used museums as a container for histories of violence that occurred there. I was really interested in how wars and events of death and destruction were then reframed by history. But, that was in Laos, which prompted me to think about these questions in my home location. So, I went to the U.S. National Archives and spent a good amount of time trying to target the images and videos of what's known as The Secret War in Laos. But I found that the information I was trying to find was scarce or obscured in some way—still secret, I suppose.

Then, in the project for the Frye, I continued this interest in the archive and what can be understood from it. Similar to the Laos project, I really felt like the colonialist archive that we have in places like museums didn't work. It didn't have the information I needed. In doing my research for the banner, and asking the very basic question of what the forest and the land where the Frye currently stands was like prior to the arrival of European settlers, I came to realize there's just not very much information about forest structure in Seattle museums. I found that a better understanding came from talking with people inside of the Duwamish tribal community, as well as books that relied on the expertise of Coast Salish people to reconfigure the area’s history.

Images Wechsler took while exploring Roanoke Park, Saint Edward State Park, and Discovery Park, in King County. Courtesy of the artist

EL: I’ve heard you speak about the way the information you learned from the Duwamish and Coast Salish people led you to particular sites throughout Seattle that you considered as you were deciding what to photograph for the banner. What were you looking for in those sites?

SW: First of all, it was really hard to find a place that had all of the elements I was looking for in terms of the ecological history of First Hill. The steepness of the terrain was really important to me to capture, as was the particular forest structure that I was looking for. Most Seattle parks have a lot of bigleaf maple, but my research did not lead me to understand that as a dominant species for this location.

I also had a really specific criteria for how I wanted the image to fill the space. I wanted it to feel like you, as the viewer, are intersecting the space and that the scale is appropriate. You're not looking up or down, you're looking at the tree straight-on. I wanted it feel like a little window.

As a photographer, I was also struggling a lot with wanting to be cognizant of the fall and winter seasons when the banner would be shown and the reality of the summer in which I was taking the photographs, which had a lot of green-on-green-on-green-on-green. Despite the difficulties of the parameters I’d set up, it was exciting to be out there in the city, finding bits of what I'd been reading about and thinking about. I could feel the research coming together in my brain, even as it felt like this puzzle that I had to work through.

Sadie Wechsler. Between the Tideflats and the Lake, 2021. Digital photograph on vinyl. 16 x 20 ft. Courtesy of the artist. Installation view from Boren Banner Series: Sadie Wechsler, Frye Art Museum. Photo: Jueqian Fang

EL: Did it feel different to think about this work as one that people encounter outside of the museum, most often as a passer-by?

SW: Yes, absolutely. I thought about the construction workers who are there everyday, working on the projects currently going up in First Hill. And the people who are commuting into downtown, or traveling out of town. And people going to the hospitals, where I have heard you can sometimes see the banner from the windows. The circumstances of it being a banner set up such a different type of interaction, so I was thinking a lot about the possibility that viewers who otherwise spend less time with art in general would be interacting with it.

I also thought a lot about the different speeds of these encounters with the work. The person who's driving by will have one experience, but the person who sees it day after day after day, as they're working on the construction site, will have a different kind of interaction with it. As will the person who walks by on the street once and looks up at it. All of those different types of viewership were interesting to me.

I've always been really interested in advertising materials, especially the connection between landscape photography and advertisements. The medium was used to pull settlers west and to sell the concept of Manifest Destiny. I think that we don't consider the early photographs and wet plate images of the railroad as advertisements. But really, that's what they were doing. And so, I was thinking about those histories in relation to the banner’s conception as well.

One of the things I love about a photograph is that it's static. Our brains can look at an image for two seconds and take it in and compartmentalize it and think we understand what's going on. And then, we can also spend much longer with it and have a totally different response. I love making images that break down or get more complicated with close looking.

Interview by Erin Langner

Exhibitions and Publications Coordinator