Mary Ann Peters’s work is featured in the exhibition Recent Acquisitions in Contemporary Art (on view September 11, 2021–January 23, 2022). She spoke to Frye staffer Erin Langner about this trembling turf (the shallows) (2018), which became part of the Museum’s collection in 2019.

Mary Ann Peters is a Seattle-based artist whose combined studio work, installations, public art projects, and arts activism have made noted contributions to the Northwest and nationally for over 35 years. Most recently her work has focused on the overlap of contemporary events with splintered histories in the Near East. Her art has previously been on view at the Frye in exhibitions Genius / 21 Century / Seattle (2015-16) and Chamber Music (2013).

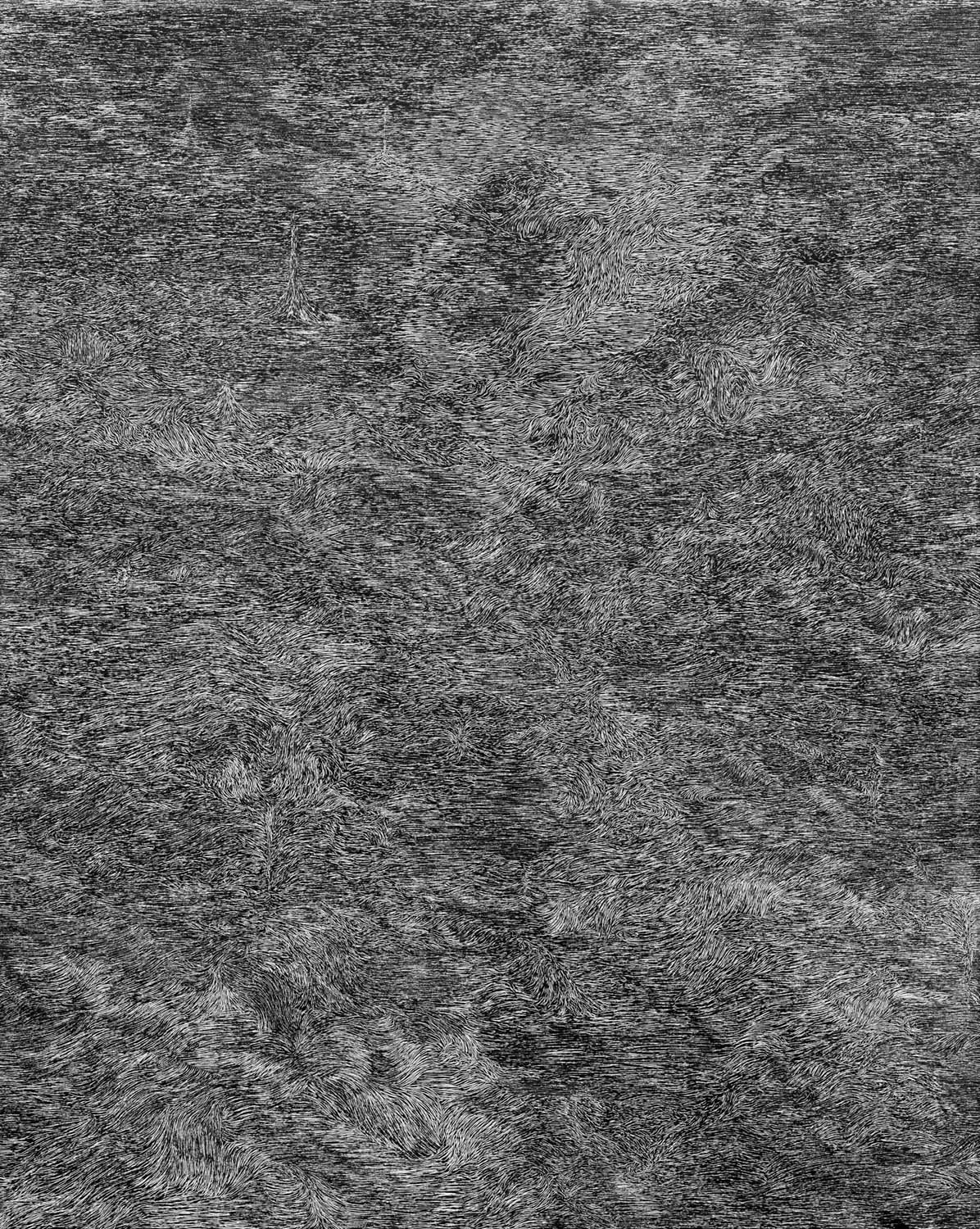

Mary Ann Peters. this trembling turf (the shallows), 2018. White ink on clayboard. 60 x 48 in. Purchased with funds provided by Seattle Art Fair, 2019.005

Erin Langner: Perhaps we can begin at the materials level. Given how many mediums you’ve worked with throughout your practice, how did you decide to work with black clayboard and white ink for the this trembling turf series?

Mary Ann Peters: The clayboard actually, as a choice of a surface and a material, came many years ago. In 1997, I was invited to Istanbul for a residency. And I had been creating work on plastered surfaces that I was making myself— I was just trying to find a way to be more mobile with the character that I was creating on those surfaces, and I found clayboard. The manufacturers have been working with me, thankfully, doing custom panels and supporting the way I'm using their product because it's not typical. The black clayboard is normally like a scratch board, so people would scratch the image. I think sometimes when people look at my drawings, they think that's what I've done. But in fact, I use a pigment ink with a pen.

I think it was partially because I wanted to make an image on a black surface. The title always drives the image in some ways—and I consider them heavily before I put them out in the world. As I honed in on the notion of “trembling turfs,” I wanted to see if I could translate what I was learning, which was about how this agitated earth aligned with hidden narratives. And I just kind of... truthfully, I just started. I just started making it. I made the very first one trying to imagine what you would see if you could stand beneath the earth with a horizontal view.

EL: How did you come to this trembling turf as a title?

MAP: I had been invited in 2016 to a residency in Beirut. I had already done residencies in Mexico City and in Paris, looking for the overlap of migration patterns and histories that started at the turn of the twentieth century, with my family's immigration from Greater Syria to this country. I wanted to look at the parallels, if they existed, and to look at the trajectory. My family left with the collapse of the Ottoman Empire. And there were a lot of reasons why they left. Everything from... just to have more opportunity, to young men being conscripted by the Ottoman Army and not wanting their sons to experience that.

And so, I just would go into archives—all of those cities had remarkable archives. When I was invited to Beirut, I went to the Arab Image Foundation, which was founded by artists and photographers from the region. They wanted to have a kind of citadel— a site where their imagery and perspectives on the places they lived could be collected.

While I was looking through a book in their archives, I found unexpectedly a very, very short paragraph. This has been my experience in some of the sources that I've used to make my images and my installations: there was a rumor. In this case, let's say there's rumor of a mass grave under a golf course. The only golf course in Beirut. And it happens to be adjacent to a Palestinian neighborhood. It aligned with a quite horrible event that happened in the Shatila and Sabra camps in Beirut. The reason I say it was disputed is because nobody wants to lay claim on what was a truly horrendous event, but it did indeed happen. And whether or not there is a mass grave under the golf course, it seemed possible. But nobody would say. So it was this little tiny, tiny, sliver of information in a book that triggered my thinking for the series.

This falls under something that I think is important for artists. I think an ethical dilemma arises when artists decide to use real events as sources in their work—unless they are absolutely sure about the layout of their sources and of their trajectory—do you use these sources or not. And in some cases, I think artists should not use them.

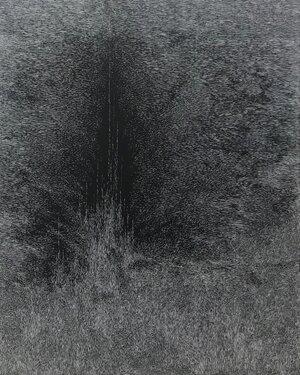

Mary Ann Peters. this trembling turf (burst), 2019. White pigment ink on black clayboard. 60 x 48 in. Seattle University Permanent Art Collection. Courtesy of the artist

Knowing this, thinking this way, I started to consider questions like, how do you find hidden histories? How do you find things that are not necessarily discussed within the mainstream narrative of a place? And, I became interested in forensic archeology and anthropology. I learned that there is a device which is like a sonogram that skims the earth. When it detects something solid, the device pulses, just like a heartbeat. And I just ran with that.

this trembling turf is more of a global concept, because every culture has hidden histories that they don't want to cope with. It's never that nobody knew what happened. For the title, I just was playing with words and trying to see if I could evoke terra firma, the land, and suggest that it's always in a state of flux and agitated, and that it's dense and holds history.

When I add a parenthetical to titles in the series, like the piece at the Frye, called this trembling turf (the shallows), that happens as I am making the image; I don't have a preconceived trajectory, I just start drawing. There are some habits I return to, maybe the way I'm creating the marks, or if I determine I want a really horizontal perspective, I'll do that. But this trembling turf (the shallows) started to become really dense, and it looked to me like things bubbling up to the surface.

These pieces are interpretations. For (the shallows), I was thinking of marshlands. I was thinking of settings where you can see lots of activity in the earth and on the earth. But, you don’t know what’s just below the surface unless you really dig into it. “The shallows” is also a poignant term for what I'd call accessible terrain. Because it's not so submerged or buried that you couldn't—if you wanted to—discover things in the land. Some of the other works in the series were about water and what happens in forced water crossings. They raise questions like, what does the water swallow up?

EL: And then I learned that just this past May you finished the series, which now includes ten works.

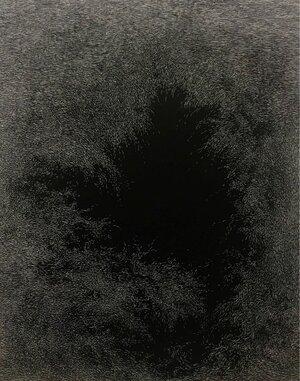

Mary Ann Peters. this trembling turf (the hollow), 2021. White pigment on black clayboard. 60 x 48 in. Courtesy of the artist and James Harris Gallery

MAP: Yes, the very last is the only one that doesn't have a pulse somewhere in the drawing. The others all have a pulse—somewhere that says: there could be something there. This last one is called this trembling turf (the hollow). And I did that intentionally, because it's an image that is a swirl of sorts, and it ends in a black empty space. To my mind, it just lays the groundwork for what could happen in the future or all the things we don't know. And we'll never know. And when I got to that point, I thought, Okay, that's it. I don't need to make any more.

EL: Was it hard to come to an ending of the series, particularly during the pandemic, as I’ve heard from many other artists about how it has been a challenging time to create work?

MAP: No, it was harder to decide that I needed more. I finished the ninth work, and then I thought, This isn't it. I knew that there was something missing. Thankfully, I still had one panel that I had already purchased. So I thought, Okay, you’ve got one black panel left and you’ve got to deal with it. And it just started to happen.

EL: I recall a comment you made on your Instagram feed, about a friend who asked you, "Why would you stop making something you love to make?"

MAP: Yes, that was a really good question. And I do love making them. They're mesmerizing. But again, they, for me, are a bucket of history that I was responding to. I have the physical ability to make more of them. If somebody said, "Make me one that's twenty feet long." Would I say no? No. I would make one. Because I would give it a different purpose. But I really liked the evenness of there being ten. And personally, this body of work, the particular attention that I've brought to this work, is about a decade long. So, the number also had a symbolic closure for me.

And in my perfect world, they would all be seen at once. Before the pandemic, I was scheduled for my first one-woman museum show. We were going to bring it all together and then the exhibition was canceled because of the pandemic. People often presume my works have already been shown together in a museum, but that isn’t the case.

EL: That’s so unfortunate. Especially in thinking about the experience of seeing this series all together, given not only how long you’ve been working on it but also its role within your overall body of work and its biographical elements.

MAP: So, the biographical piece. Now I've spoken enough about that aspect that people understand it to be prescient in the series. But for me, the narratives that I've been lining up with this work are a little bit more universal. And I think they should be. There are so many surface reasons that artists of Arab descent are frequently on the periphery of discussions surrounding diversity and inclusion. I know in my own case, people don’t often guess my background because my name has been anglicized. But it may also be because I’m bringing a different perspective, as someone using a second-generation lens. And I have actively spoken about this, because second-generation perspectives should be as integral as firsthand evidence and responses. This is how history unfolds. This is how cultures are embellished and move and maintain a sense of fluidity.

In all the research I've been doing, one of the constants has been learning that, even if I arrive at a narrative that I know isn't definitive, it's time-based. So, a decade later, fifty years later, one hundred years later, there's only a hint of that perspective. And what do we do with that? Is that dismissible? Or do we fold it over into a new narrative that's more contemporary? Partly why I am not only looking at history, but also at contemporary events is because there are overlaps. And I hope that when people are seeing my work, there is a sentiment that comes through.

But I started doing this work because I wanted to escape just having a sentimental tie to my Lebanese family and histories. A lot of my family wouldn't understand why I'm doing this. They see the connection between past and present as being important, but they don't necessarily see it as a foothold for how their experiences have been affected. And I get that. I get it. But I just wanted to know about it. I felt like I was uninformed and now... I know more than I ever imagined.

Interview by Erin Langner

Exhibitions and Publications Coordinator