Kalup Linzy’s work is featured in the exhibition Black Refractions: Highlights from The Studio Museum in Harlem (on view May 22–August 15, 2021). He spoke to Frye staffer Erin Langner about his artistic and personal trajectory and current projects.

Kalup Linzy. OK (still), 2021. Digital video (color, sound); 10:55 minutes. Courtesy of the artist and David Castillo

Kalup Linzy is a video and performance artist who grew up in Stuckey, Florida and is currently based in Tulsa, Oklahoma. His best-known works include videos that satirize the conventions of the television soap opera and question ideas of race, gender, class, sexuality, and identity. Linzy works on all aspects of his productions, including writing, directing, acting, and filming.

His video work Melody Set Me Free (2007) is on view at the Frye in Black Refractions: Highlights from The Studio Museum in Harlem. Melody Set Me Free revolves around the earnest protagonist Patience O’Brien (played by Linzy), who leaves her hometown to pursue her dream of becoming a star in an American Idol-style singing contest. I interviewed Kalup to find out more about this piece and his current work.

Erin Langner: As someone who grew up in Florida and then later moved to New York, what was your relationship to the Studio Museum leading up to If it Don’t Fit (2009), your first museum solo exhibition. Were you familiar with the Museum before you moved to New York?

Kalup Linzy: During graduate school at the University of South Florida in 2000, I remember being in my mentor’s office, and an article came out in the New York Times, talking about [then curator] Thelma Golden and [then director] Lowery Stokes Sims and the direction the museum was going. I also remember the Museum being on my radar when I was at the Skowhegan School of Painting and Sculpture. I don't know if it was that article, or that I ended up discussing the Museum’s Freestyle (2001) exhibition with some of the other artists—because that was a year when the school let in a lot of artists of color—but we also talked about the Studio Museum.

When I graduated in 2003, I applied to the Studio Museum’s Artist-in-Residence program. I did not get into the residency, but I moved to New York that year and ended up applying a couple more times. Around that time, artist Derrick Adams curated a group show at Rush Arts Gallery that included my work. I remember Christine Y. Kim [then curator] from the Studio Museum coming to that opening. I had already met Thelma Golden through Kehinde Wiley by then, since we were all hanging out together.

Christine and Thelma ended up including my work in a show at the Studio Museum called African Queen (2005). Around that same time, my solo show opened at Taxter & Spengemann Gallery. One morning, my phone rang—it was a friend of mine, who said, "You're never going to believe this. You have a review in the New York Times." And I was like, "What?" I literally sat up in my bed because I don't even think I was awake yet. So, she read it to me, and it opened up with, “A star is born.” After that, the Studio Museum included me in Frequency (2005–06). And then in 2009, they gave me a solo exhibition: If it Don’t Fit.

After the New York Times review, I wasn't expecting any of the other attention that happened. I thought those videos would lead to someone hiring me—you know what I mean? I thought, I'll go work for somebody else. And, lo and behold, my videos took on the life of their own in the art world, so I just kept doing them.

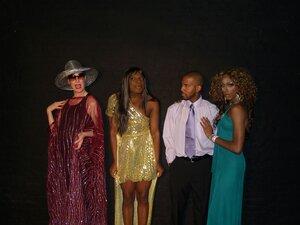

Kalup Linzy. Melody Set Me Free (still), 2007. Digital video, color, sound. TRT: 00:15:10. The Studio Museum in Harlem. Museum purchase with funds provided by the Acquisition Committee 2009.1. Courtesy the artist and David Castillo Gallery

EL: The style of your videos is so distinct, it is something I think about every time I see Melody Set Me Free.

KL: I always worked with what I had. And so sometimes that wasn't a lot. I think All My Churen (2003) was shot with a camera from my school, because that was my thesis project. And other videos, like Da Young And da Mess (2005) and As da Art World Might Turn (2006)—those were shot on a camera my aunt brought me from the Home Shopping Network. KK Queens Survey (2005) was shot on a camera that I borrowed from my former professor, who was teaching at Rutgers University and borrowed it from their art department. And so I was just getting those videos done with whatever I had, you know? And it's still kind of that way.

Melody Set Me Free was shot on my own camera— a MiniDV I got in 2005. I started getting grants and fellowships around that time, so I had upgraded by then. And I'm sure I had production assistants, because I had purchased lights.

EL: I am curious about the Patience O’Brien character that you play in Melody Set Me Free, given the way her biography seems to have some overlap with yours. Do you see her that way?

KL: Well, I think back then, I superficially saw it that way, but I wasn't comparing it to my own experience. Sometimes when I look back, I can see the parallels. But I can also say that it was more about me looking at old Hollywood films and thinking about them in relation to video and performance art. And also, my obsession with Whitney Houston. It wasn't so much about my desire to be in New York— I was already in New York.

For whatever reason, I haven't been able to completely eliminate my Southern accent. So, I had Patience coming from—in fact, most of these characters were coming from down south to New York to be in an American Idol-type contest. That way, I didn't have to alter my accent. I was actually thinking of the movie A Star is Born. But, Holland Cotter opened up his review of my work with, “A star is born.” So I can see why people would say the character is self-referential.

But, I was also thinking of The Wizard of Oz. Patience is going to be in a talent contest, and then she meets this guy. Her journey is like Dorothy’s—a tornado doesn't happen, but the talent show gets her from her small town to New York. And, when she arrives, she has on this gold dress, which represents the yellow brick road. Then, she starts meeting all these characters, who are wearing colors that represent the Emerald City, but also their personalities sometimes reflect the movie. Sahara Davenport is, of course, wearing a green dress, and that's sort of referencing the Wicked Witch.

So, yeah, it represents me coming from a small town to the city of New York. But, that also relates to those movies—just being on that journey as an artist or even as a human. Of course, I've always had the desire to meet someone and fall in love and have this great career and all of that sort of thing. But, I think most humans want to have that connection with another person, right? So, it plays on those emotions as well.

I also studied Joseph Campbell—The Hero with a Thousand Faces and the twelve steps of the hero’s journey that he theorizes are part of most movies. The twelve steps are definitely in A Star Is Born and The Wizard of Oz. And, as humans, that journey is the sort of thing that we identify with. So, some of that comes in play, too, in terms of the craftsmanship of Patience’s story.

EL: How did you decide to leave New York and ultimately land in Tulsa, Oklahoma, where you’re in residence at the Tulsa Artist Fellowship?

KL: Basically, in 2015, I was like, Okay, I need a break. I was applying for grants and they weren't quite coming through. I didn't really want to leave New York, but I put my stuff in storage, went down to Florida, and then about a month after I got there, things starting happening. I found out I won the New York Foundation for the Arts fellowship. And then, I was receiving commissions and being invited to do lectures in different places, so I ended up half-living in New York, staying in hotels. For the next few years, I was traveling to shoot videos and teach and give lectures—just flying all over.

And so it was sort of bananas, but in all of that craziness, my mother was diagnosed with cancer. By the end of 2017, I was getting ready for Art Basel Miami Beach, and my mother wasn't looking well. And so it was real bad, but I just got through the performances I did at Art Basel, which were all over the press. So, you wouldn't have known what I was going through.

My mother passed away that January. I decided to do the Recess studio residency in New York because I was like, Okay, I just need to keep busy. And around that time, I applied to the Tulsa Artist Fellowship. I had heard about the fellowship before, but I didn't apply, because I was like, Tulsa? I couldn't wrap my brain around it. Fast-forward to 2018, my mother passed, and I decided I just needed a breather and some stability.

EL: And now you’ve been in Tulsa for three years. I recently read about your moving project in BOMB magazine, “On the 1921 Tulsa Race Massacre.” What else have you been working on?

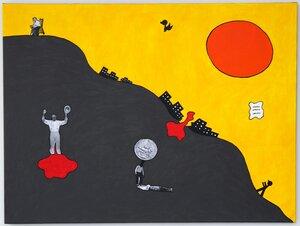

Kalup Linzy. I'm Coming Up—1921 Tulsa Race Massacre, 2021. Mixed-Media. 48 x 36 inches. Courtesy of the artist

KL: So, three months after I got here, I went to the dentist to get one of my wisdom teeth taken out. And the dentist was like, "I can't do it. Your blood pressure is too high— if we try to pull it, you're at risk of having a heart attack or a stroke." All along, I’d been thinking these headaches I’d been getting and the shifts in my energy were just from stress. And then the doctors confirmed I had hypertension. They were like, "Oh, you probably have some kidney damage. You have to change your diet and do this, that and the other." But then, last March, I got a letter in the mail right as the pandemic kicked in. It said, "Thank you for choosing St. John's for your stage three chronic kidney disease.” And I was like, What?

I literally went through this weird period of kind of accepting death and making peace, because I just didn't know what was going on and how long I had. The stage I was at, I was supposed to die at age 66, which was my mother's age when she passed away. So I kind of freaked out. I was like, Oh gosh, this is too bizarre. And so, I started getting my blood tested regularly. I changed my diet, I changed everything. I lost 30 pounds. And now everything is stable. My nephrologist says I have enough kidney functioning to last something like 40 years.

Taking all that into consideration, I feel like I have to go at a slower pace. So I decided to start an art house here, with an artist residency. I did not plan to stay in Tulsa longer than three years. But the fellowship program was recently restructured in a way that I could keep applying to renew funding for up to seven years.

I don't believe in cutting myself off from my past places. I believe in building on them. So, I'm still connected to my family in Stuckey. I'm still connected to my friends in Florida, to the school I attended there. And I'm still connected to friends in New York, as well as institutions. But, I have also met a lot of musicians here in Tulsa that I'm able to work with. You know, there are already artists here, and I'm just wanting to build on that and add to it. So, my project is going to be an artist residency within a social space. It's going to be called the Queen Rose Art House, named after my Queen Rose Family (da Stories) installation (2015). And, I'm going to invite artists from out of town to come out for about a month, and they'll get a stipend and a roundtrip ticket.

When the Tulsa fellowship is over, I hope to continue the project. I've already been thinking I possibly want to do an outpost in New York or Florida. But I also want to see how the art world is going to respond to it. That'll inform what direction I should go, once the fellowship starts to wind down.

I know other artists have been starting residencies, and it is something that I always dreamed about quietly but didn't think I could do. When I received the funding, I thought about just shooting a film. But, a film may or may not have a lasting impression. I know that an artist’s residency for emerging artists, or artists who haven't quite gotten a break yet, would really mean a lot to them. This is more of a way to leave a legacy. And so that's basically what I want to do, and sort of shift the energy around me.

Sometimes as artists, we can be all about me, me, me, self, self, self. And sometimes the energy can turn negative. I think sometimes you have to just get out of your own head, you know what I mean? And just connect with other humans.

Kalup Linzy. Walk on By (still), 2021. Digital Video (color, sound); 3:19 min. Courtesy of the artist and David Castillo

Erin Langner

Exhibitions & Publications Coordinator