Collection Connection is a series of personal responses by Museum staff to works in the Frye Art Museum’s collection.

As an American child of the 1980s, I grew up without much real interest in the British monarchy but a vague awareness of the principal characters and plot points, omnipresent as they were in the tabloids and on TV. For all her sophistication and courage, Princess Diana seemed the guileless victim of her husband Charles—who himself seemed a living caricature in my mind’s eye, somehow conflated with Alfred E. Neuman. I wondered what the lives of my contemporaries Princes William and Harry must be like and remember feeling sorry for them when their mother was killed, a shocking tragedy equally befitting Greek myth and Hollywood melodrama.

Watching Season 4 of The Crown on Netflix—which has caused an “uproar” over its historical inaccuracies—has simultaneously brought greater nuance to my understanding of these characters and underscored how little I truly understand: my knowledge of the events behind The Crown is now based primarily on childhood recollections of hyperbolic reportage and a fictionalized television drama. Plus, recognizing the uncanniness of Emma Corrin’s depiction of Diana while failing to perceive the virtuosity of Gillian Anderson’s impersonation of Margaret Thatcher is not only a letdown for this X Files fan but, I think, an indication of how comparatively little I’ve seen the latter represented. I realize I only really became cognizant of Thatcher as an adult, and then only as an abstraction, with “Thatcherism” as the British equivalent of “Reaganomics” in the emergence of neoliberalism.

So, while the royals are essentially just residual figureheads—“tribal leaders in eccentric costume” to quote The Crown— the pomp and circumstance and gossip that surrounds them has generally been more visible to the rest of the world than has the actual business of parliamentary government. In this sense, they are at the nexus of hypermediated celebrity culture and nostalgic imperial symbolism, a spectacle that at once conceals and abets the true machinations of state power. Insofar as The Crown is television entertainment, its heady mix of fact and fiction reveals the extent to which the royals and the stories we know about them are products of journalistic sensationalism and patriotic propaganda, close cousins of so-called “fake news.”

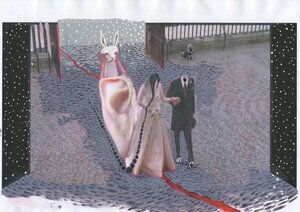

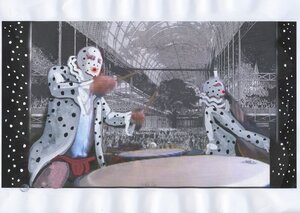

Rokni Haerizadeh. Reign of Winter (still), 2012–13. Single-channel video (color, silent); 8:42 min. Courtesy of Gallery Isabelle van den Eynde and the artist.

Rokni Haerizadeh. Reign of Winter (still), 2012–13. Single-channel video (color, silent); 8:42 min. Courtesy of Gallery Isabelle van den Eynde and the artist.

The royals’ curiously ceremonial role in modern politics has long fascinated Iranian artists Rokni Haerizadeh, Ramin Haerizadeh, and Hesam Rahmanian, who were the subjects of a survey exhibition at the Frye in 2019. The trio has worked extensively on the theme of social hierarchies and power structures embedded within public demonstrations and pageantry, drawing, at first, from their local history— the Persian/Iranian monarchy deposed through Western intervention—and broadening to the arcane, densely coded “soft power” displays of the British monarchy, among other global institutions. The Frye presentation included, for example, the 2012-2013 video Reign of Winter, a hand-painted (rotoscoped) reworking of the television coverage of Prince William and Kate Middleton’s wedding that transforms the familiar media story into a procession of grotesque beasts and monsters. Significantly, an image of the Crystal Palace—an iron and glass structure built in London for the 1851 Great Exhibition (the first “World’s Fair”)—is superimposed over Westminster Abbey in the video, pointing up the imperial undertones of such public rituals.

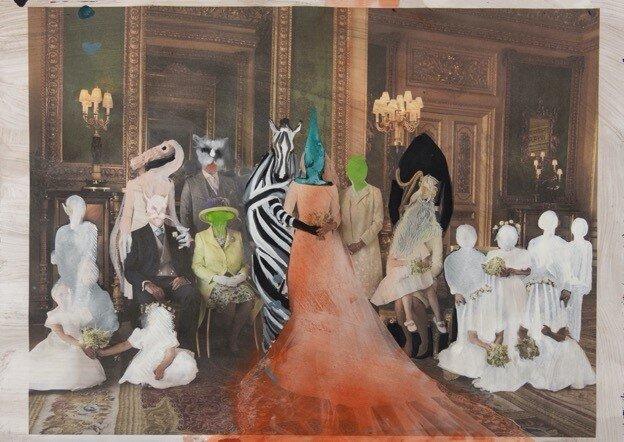

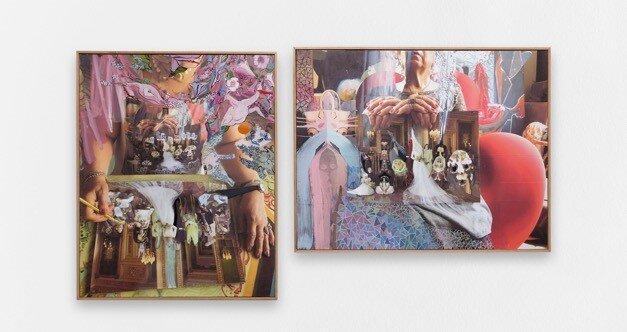

Following the collective’s 2019 exhibition, the Frye acquired the trio’s 2016-17 video From Sea to Dawn as well as a painting on paper attributed to Rokni, If Marco Polo Brought the Pasta Meme to Europe from China, He didn't Need to be a Pasta Chef but all he Had to do was to Disperse the Meme in the Environment and Other Humans Infected by it, Would Express it in their Behavior (2017-18), pictured at the top of the post. An alteration of Prince Harry and Meghan Markle’s official wedding portrait, the latter is one of a series of works—including modified images of protests, military actions, political summits, and so on—created under this title, which is based on a quote from American philosopher Daniel Dennett’s writings on cultural evolution.

Dennett’s theories draw on Richard Hawkins’s concept of “memes” as ideas that replicate from brain to brain like genetic messages encoded in DNA or—perhaps more topically—like viruses transmitted through, but not necessarily always expressed by, their carriers. So, returning to where I began, I might not have any direct knowledge of the royals and may not usually have occasion to think, talk, or post about them but I nonetheless act as a carrier of (mutated?) cultural information about them. My notions reflect a kind of natural selection process in which the most replicated images and narratives become the defining traits of popular belief. Like memes in microcosm, images also circulate among and mutate across the trio’s paintings, collages, and videos.

Rokni, Ramin, and Hesam’s work might generally be said to reflect on and complicate the transmission process by calling viewers’ attention to their own role in the replication of dominant cultural forms. Through their outlandish and obscene manipulations, they aim—as they noted in our interview—to produce "a sense of alienation or estrangement from reality…[and] as Brecht said, to ‘exorcise the sentimentalism,’ create an emotional distance, and elicit ‘astonishment rather than empathy’ from the viewer.” In discussing the origins of their approach, they cite the influence of Iranian playwright Bijan Mofid’s musical Shahr-e Qesseh, or City of Tales (1968), an Animal Farm-esque meditation on the strictures of pre-Revolutionary Iran that satirized political events through a cast of animal characters. Their work has been found effective by those in power, too: they have lived together in self-imposed exile in Dubai since Rokni and Ramin’s artworks were confiscated from Tehran collections in 2009.

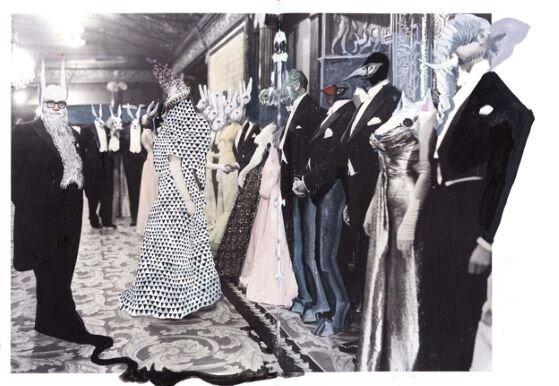

For all that, it must be said that the artists are also having fun. Their 2016 book project Her Majesty?—a complete modification of the 370-page coffee table tome produced by Taschen Verlag to celebrate the 60th anniversary of Queen Elizabeth II’s coronation—serves up plenty of humor alongside pointed critical references to terrorism, racism, and gross inequality. And really, what could be a more obvious target for campy parody than the British royal family? The absurdity of divine right aside, there are already funny hats, petty squabbles, and ridiculous customs. Ibble Dibble, anyone?

Her Majesty?, 2016. Courtesy of the artists.

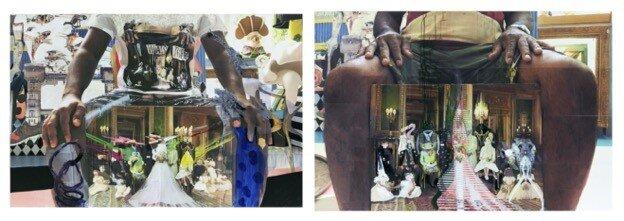

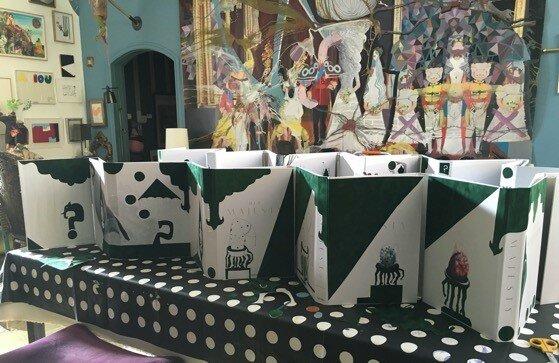

in process. One of the collective’s paintings featuring altered imagery of the British

royal family is visible in the background. Photo courtesy of the artists.

Amanda Donnan

Chief Curator