Seattle artist Rafael Soldi uses photographic media to examine the intersection of individual identity with larger political and social themes such as immigration, memory, and loss. The artist’s current work builds on his experience as a queer youth in Peru to focus on the construction of masculinity in Latin American society. Soldi's image for the Boren Banner Series Mientras el cielo gire (As long as the sky whirls) is from a new project based on his research into the Peruvian Havana Embassy Crisis of 1980 and the ensuing Mariel Boatlift. In the following post, Solidi discusses the project and the history at its center. A Spanish version of Soldi's essay is available half-way down the page.

Mientras el cielo gire (As long as the sky whirls)

By Rafael Soldi

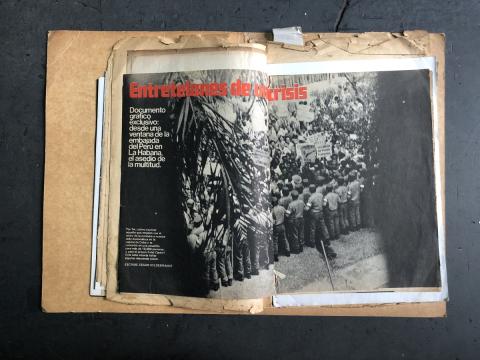

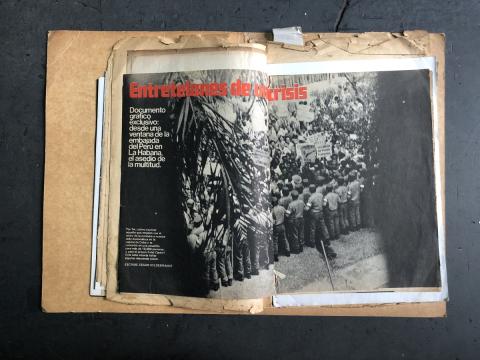

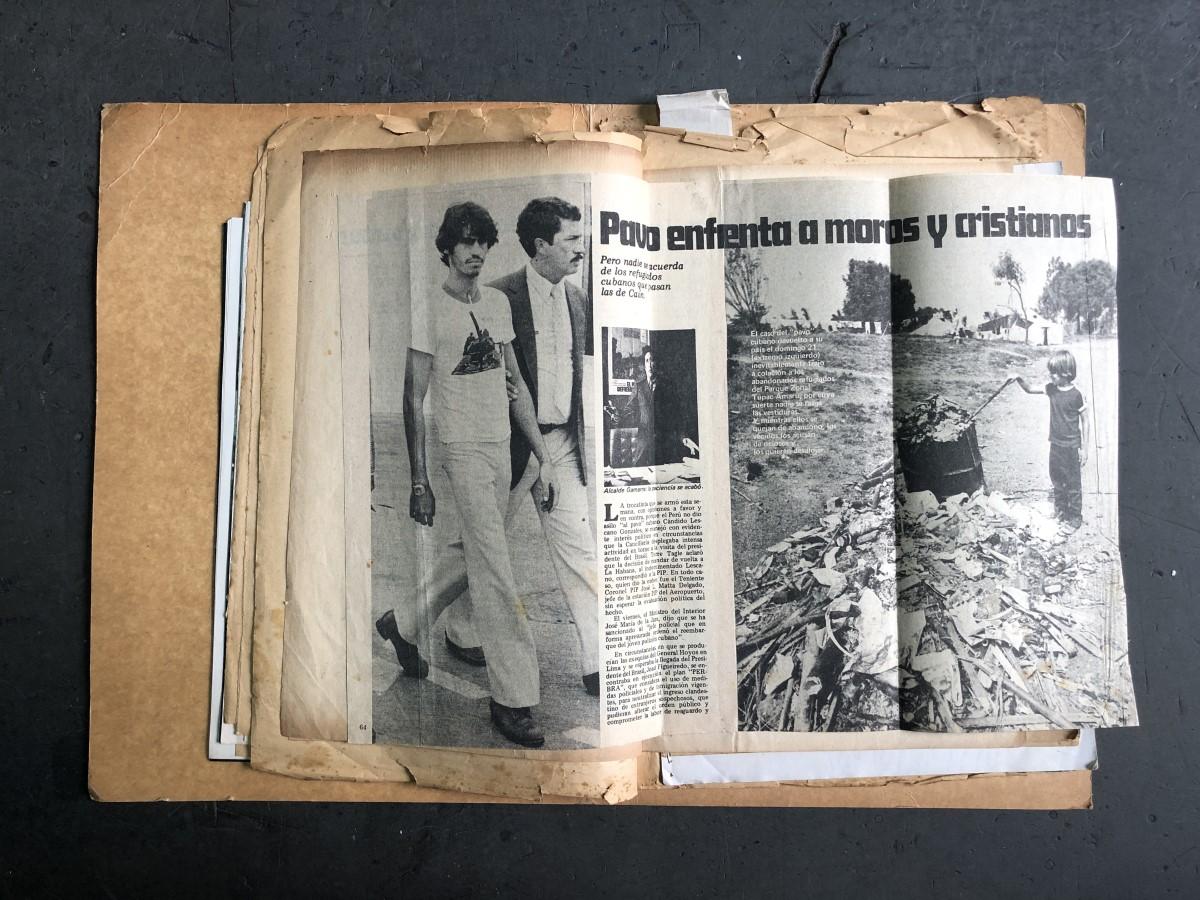

In April of 1980, six Cubans crashed a bus through the gates of the Peruvian embassy in Havana. By the end of that week 10,000 Cubans seeking asylum had taken refuge inside the embassy grounds after Cuba removed its security forces that protected the buildings. After nearly a month of a humanitarian crisis, and due to global pressure, dictator Fidel Castro was forced to authorize those in the Peruvian Embassy to exit the island through the port of Mariel, 25 miles north of Havana. Pressure continued, and Castro announced that anyone else wishing to leave Cuba could do so, but had to register as a homosexual, deviant, criminal, or otherwise useless to the revolution. A massive flotilla of private boats arrived from Florida and by October 1980, 125,000 Cubans arrived in the United States. Peru welcomed 1,000 refugees. In all, it is estimated that up to 20,000 gay Cubans may have left the country.

Being a homosexual was the most heinous crime in Cuba at the time—queer people were forced into labor camps or prisons. Reinaldo Arenas—a queer writer who was persecuted and eventually imprisoned for his “deviant” writing and his homosexuality—details his difficult and beautiful life in Cuba—and his eventual narrow escape in the chaos of the Mariel boatlift—in his memoir Before Night falls. He writes, “I have always considered it despicable to grovel for your life as if life were a favor. If you cannot live the way you want, there is no point in living.”

The Cuban government characterized those who fled as undesirables, antisocials, lumpenproletariat, and escoria (scum), and added that the United States was “performing a tremendous sanitary service” by accepting them. Ironically, for gay Cubans who had been persecuted and incarcerated for decades, public admittance to their homosexuality became the surest way to freedom.

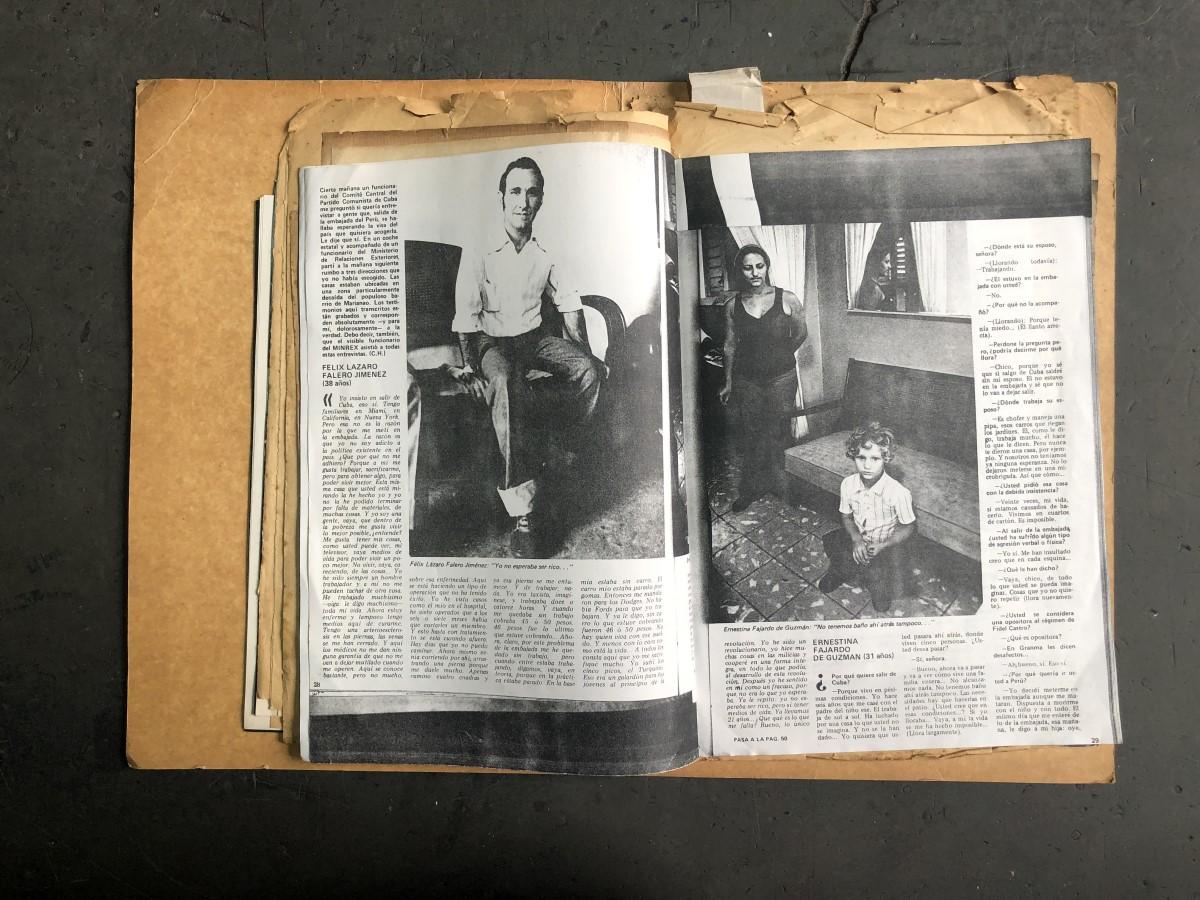

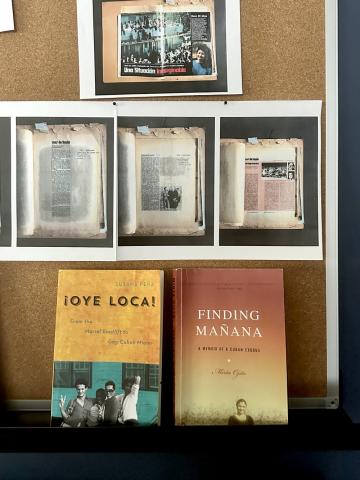

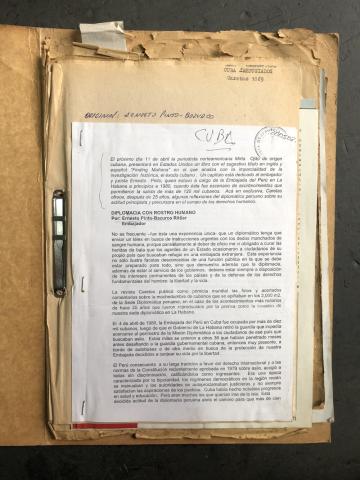

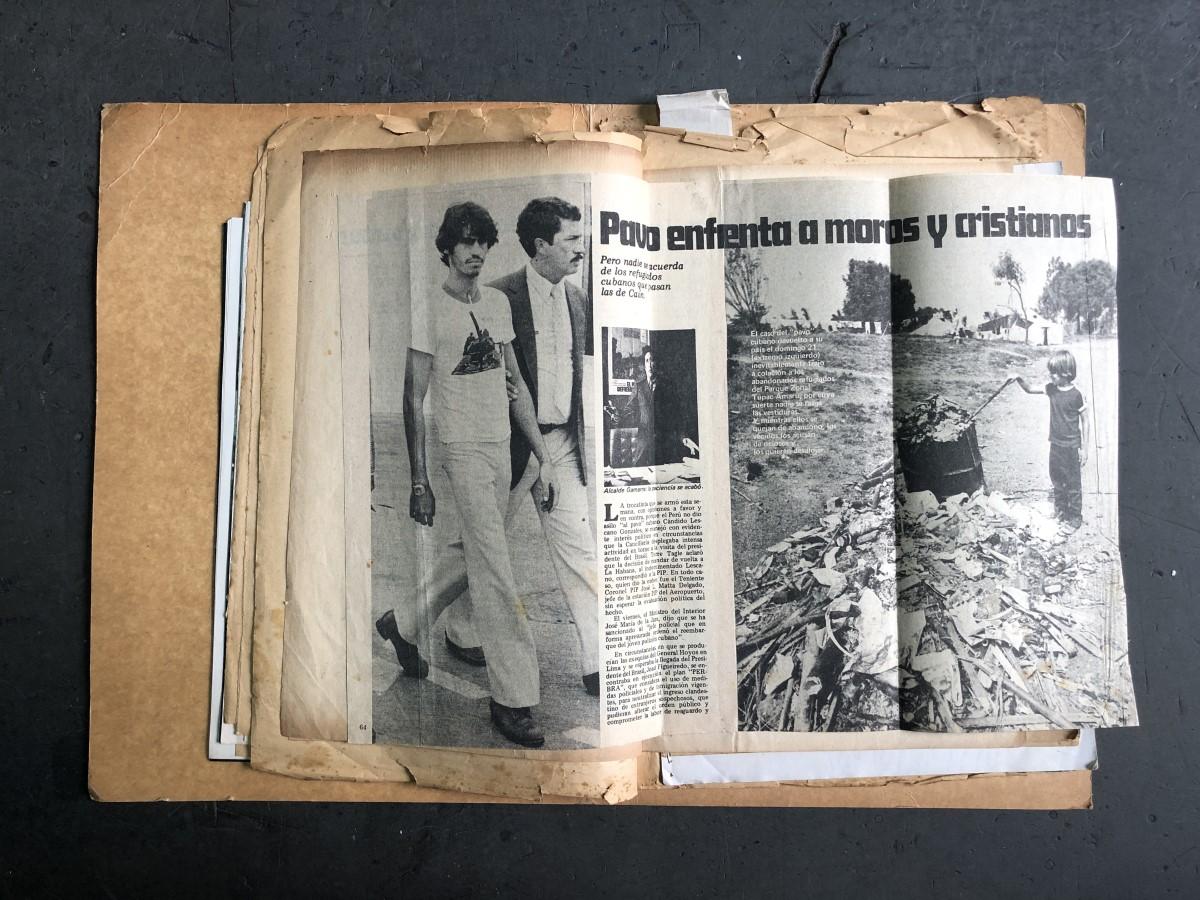

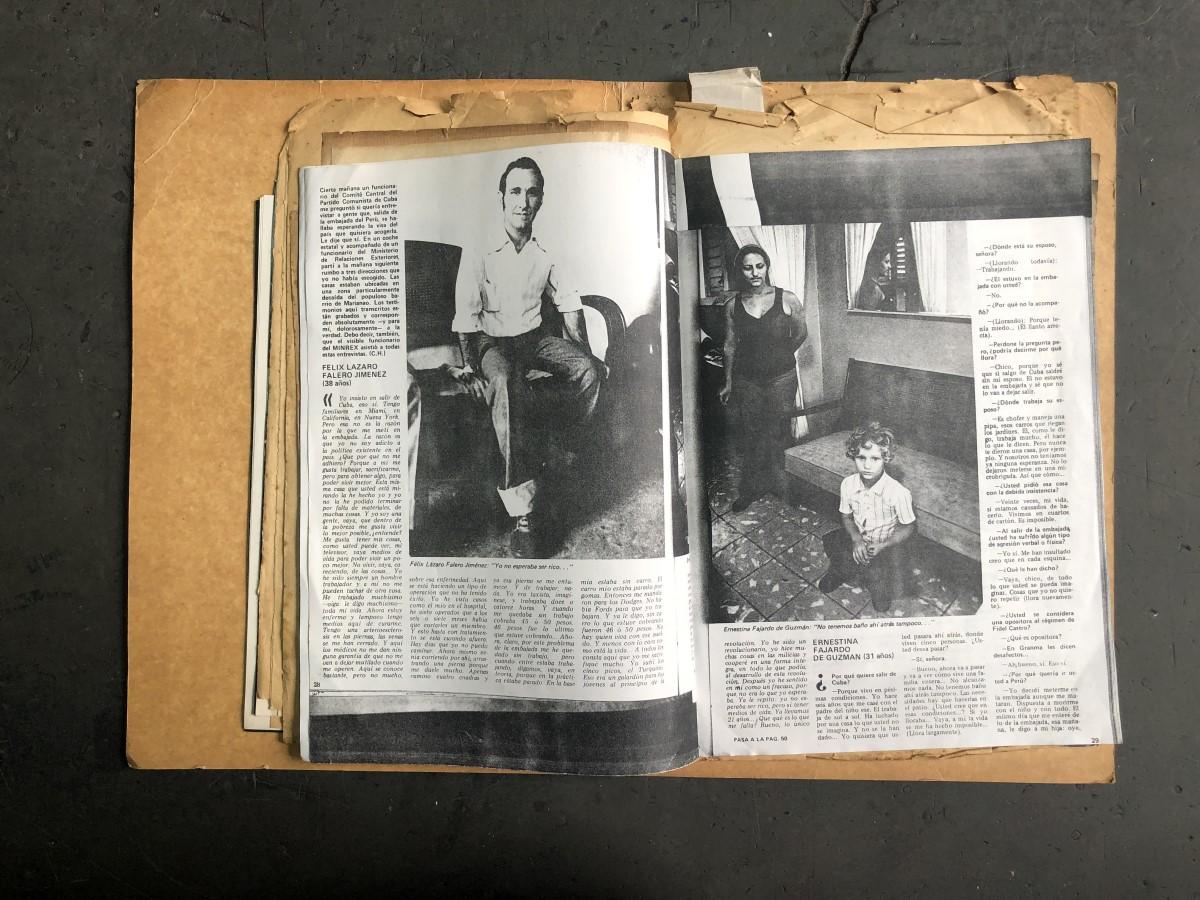

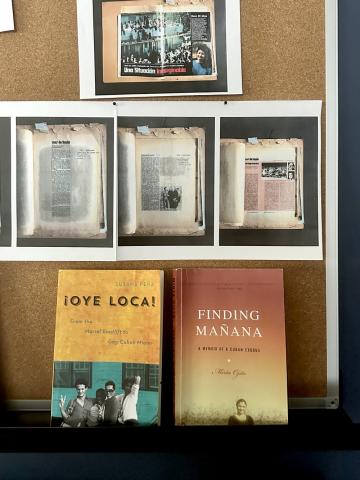

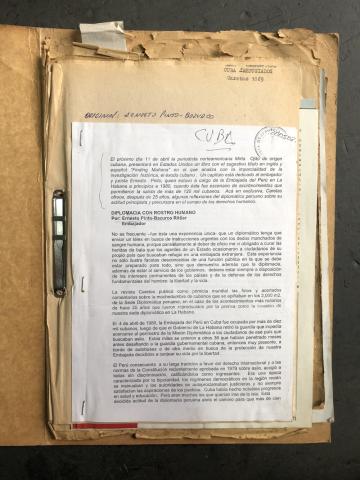

My interest in this historic happening centers on the inadvertent role that my homeland of Peru played as a gateway to queer liberation, despite its long history with homophobia. In 2019 I visited newspaper and political magazine archives in Lima, Perú, to photograph and acquire archival source material related to this event. The material covers both the events that took place in Havana, and the large resettlement of Cuban refugees to Lima. The Mariel boatlift and the events around it have been extensively researched and discussed in the public, especially in Cuban communities because it changed the course of their history and largely created the social dynamics of modern Miami. What I am interested in are the personal queer narratives that stream below the surface of the public accounts largely concerned with political questions. Beneath the egos of powerful men playing global political chess, there are real queer people for whom, as Arenas put it, “There’s just one place to live—the impossible.”

I intervene these archival images by cropping and obstructing their narrative, transforming an ostensibly neutral journalistic account into one laden with suggestion and desire, with a gaze toward a queer body veiled in the chaos of mass exile. The title, Mientras el cielo gire (As long as the sky whirls), originates from a poem Reinaldo Arenas (1943–1990) wrote to his lover in New York City, after he escaped Cuba and shortly before he contracted HIV. The impossible narratives queer Cuban refugees embodied and survived are mirrored in these fragmented images, serving as refuge for the accounts archived in the imaginary.

In Susana Peña's essay “Obvious Gays” (Journal of the History of Sexuality, Sept., 2007, Vol. 16, No. 3, Latin American Sexualities, p. 482-524), she dissects the state’s gaze in relation to male homosexuals on both sides of the Florida Straits. Cuba’s gaze was specifically focused on outward expressions of homosexuality, and less so in private ones. Peña writes that during the Mariel crisis, “the state facilitated the exit of visible homosexuals, (...) [and] the process involved openly evaluating visible markers of homosexuality. (...) [Whereas before] the gravest crime was not same-sex sexual acts per-se but, rather, (...) appearing visibly or ‘obviously’ gay, anyone who went to the police station and declared him or herself to be a homosexual could get an exit permit.” In his memoir, Arenas recalls being processed at a local police station, “they made me walk in front of them to see if I was queer [si era loca o no]. I passed the test, and an officer yelled, ‘send this one directly!’” Peña notes that many more accounts detail this “ironic display of liberation: these men exaggerated effeminate or ostentatious mannerisms precisely in front of those government officials from whom they would most likely have hidden under normal circumstances.” In the end, the interests of the Cuban state and homosexuals wishing to leave Cuba aligned in unexpected ways—from the state's perspective this allowed them to enhance the nation’s virility and prevent future possible resistance from a stigmatized group.

These men, however, headed for a nation that had just embarked upon a national Christian backlash against gay liberation. In the U.S. federal officials felt the visibility of homosexuals contributed to the overall negative perception of the migration, and records exist of the government’s various efforts to count, categorize, and document gay Cubans entering the country. Visible homosexuals were more likely to be detained in the settlement camps and confined for longer periods of time. Peña concludes that the “fractured gazes of both Cuba and the U.S. entailed real material consequences for those identified as deviant.”

While most available research centers on the massive migration from Cuba to the United States—and it is likely that this is the journey most queer Cubans made—I am choosing to source material from Peruvian archives, as it speaks to the gaze of the country that raised me. Perú played a critical role in the genesis of this event, and I hope to draw a line from queer Cubans who may have resettled in Lima to the larger inquiries in my work: immigration, memory, and loss within frameworks of queerness and intimacy. As José Esteban Muñoz writes in Cruising Utopia: The Then and There of Queer Futurity, “some will say that all we have are the pleasures of this moment, but we must never settle for that minimal transport; we must dream and enact new and better pleasures, other ways of being in the world, and ultimately new worlds.” The concept of “queer world-building” drives my practice and the construction of these images.

Mientras el cielo gire

Por Rafael Soldi

En abril de 1980, seis cubanos atravesaron las puertas de la Embajada de Perú en La Habana con un autobús. Hacia finales de esa misma semana, 10.000 cubanos en busca de asilo se habían refugiado en la embajada después de que Cuba retirara las fuerzas de seguridad que protegían los edificios. Tras casi un mes de crisis humanitaria, y debido a la presión internacional, el dictador Fidel Castro se vio obligado a autorizar que aquellos que se encontraban en la Embajada de Perú abandonaran la isla desde el puerto de Mariel, ubicado a 25 millas, o 40 km, al norte de La Habana. La presión no cesó, por lo que Castro anunció que cualquiera que deseara abandonar Cuba podía hacerlo, aunque no sin antes registrarse como homosexual, pervertido, delincuente o de alguna otra manera inútil para la revolución. Una gran flotilla de barcos privados llegó desde Florida y, en octubre de 1980, ya eran 125.000 los cubanos que habían llegado a Estados Unidos. Perú recibió a 1000 refugiados. En total, se estima que hasta 20.000 cubanos homosexuales podrían haber abandonado el país.

En aquella época, ser homosexual era el crimen más atroz en Cuba: las personas queer eran enviadas a campos de trabajos forzados o a prisión. Reinaldo Arenas —un escritor queer que fue perseguido y finalmente encarcelado por su escritura “pervertida” y su homosexualidad— narra en sus memorias, tituladas Antes que anochezca, lo difícil y bella que fue en su vida en Cuba y como, finalmente, logró salvarse de milagro en medio del caótico éxodo de Mariel: “Siempre he considerado un acto miserable mendigar la vida como un favor. O se vive como uno desea, o es mejor no seguir viviendo”.

El gobierno cubano tachó a quienes huían de indeseables, antisociales, lúmpenes y escoria, y declaró que Estados Unidos estaba “realizando un tremendo servicio sanitario” al aceptarlos. Irónicamente, para los cubanos homosexuales, perseguidos y encarcelados durante décadas, admitir públicamente su condición se convirtió en la vía más segura hacia la libertad.

Mi interés en este acontecimiento histórico ronda en torno al papel que mi país natal, Perú, desempeñó involuntariamente como vía de acceso a la liberación queer, pese a su larga historia de homofobia. En 2019, visité los archivos de periódicos y revistas políticas en Lima para tomar fotografías y recopilar material de archivo relacionado con este suceso. El material abarca tanto los acontecimientos ocurridos en La Habana como el gran reasentamiento de refugiados cubanos en Lima. El éxodo de Mariel y las circunstancias que lo rodearon se han investigado y debatido profundamente en la esfera pública, en especial en las comunidades cubanas, dado que cambió el curso de su historia y, en gran medida, creó la dinámica social de la Miami moderna. Lo que me interesa, en particular, son las historias de personas queer que flotan por debajo de la superficie de los relatos públicos, principalmente centrados en cuestiones políticas. Detrás de los egos de los hombres poderosos que juegan al ajedrez de la política internacional hay personas queer reales para quienes, como expresó Arenas, “Sólo hay un lugar para vivir, el imposible”.

En mi práctica, intervengo estas imágenes de archivo recortando y obstruyendo su narrativa para transformar un informe periodístico ostensiblemente neutro en otro cargado de insinuación y deseo, con una mirada del cuerpo queer velada por el caos de un exilio masivo. El título, Mientras el cielo gire, proviene de un poema de Reinaldo Arenas (1943–1990), escrito para su amante en la Ciudad de Nueva York tras escapar de Cuba y poco antes de contraer VIH. La narrativas imposibles que los refugiados cubanos queer encarnaron y sobrevivieron se reflejan en estas imágenes fragmentadas, que sirven de refugio para las historias que se archivan en el imaginario colectivo.

En su ensayo “Obviamente gays” (Journal of the History of Sexuality, sept., 2007, Vol. 16, n.° 3, Latin American Sexualities, págs. 482-524), Susana Peña analiza minuciosamente la mirada del Estado en relación con los hombres homosexuales a ambos lados del estrecho de Florida. La mirada de Cuba se centraba específicamente en las expresiones externas de la homosexualidad y se interesaba menos en las privadas. Peña escribe que, durante la crisis de Mariel, “el Estado facilitó la salida de personas visiblemente homosexuales, (…) [y] el proceso supuso la evaluación abierta de marcadores visibles de la homosexualidad. (…) [Mientras que antes] el crimen más grave no eran los actos sexuales con personas del mismo sexo en sí, sino (…) parecer visiblemente u “obviamente” gay, cualquier persona que se presentara en la estación de policía y se declarara homosexual podía obtener un permiso de salida”. En sus memorias, Arenas recuerda ser procesado en una estación de policía local: “A mí me hicieron caminar delante de ellos para comprobar si era loca o no. Yo pasé la prueba y el teniente le gritó a otro militar: «A éste me lo mandas directo»”. Peña destaca que muchas otras historias detallan esta “irónica demostración de liberación: estos hombres exageraban gestos afeminados o llamativos precisamente frente a los mismos funcionarios del gobierno de quienes habrían tenido que ocultarlos en circunstancias normales”. Al final, los intereses del Estado cubano y de los homosexuales que deseaban abandonar la isla se alinearon de forma inesperada: desde la perspectiva del Estado, la situación les permitía aumentar la virilidad de la nación y prevenir una posible resistencia futura por parte de un grupo estigmatizado.

Sin embargo, estos hombres se embarcaron hacia un país donde acababa de iniciarse, a nivel nacional, una violenta reacción cristiana en contra de la liberación homosexual. En Estados Unidos, los funcionarios federales sentían que la visibilidad de los homosexuales era parte del motivo por el cual existía una percepción general negativa de la inmigración, y existen registros de los diversos esfuerzos del gobierno por contabilizar, categorizar y documentar a los cubanos homosexuales que ingresaban al país. Aquellos que eran visiblemente homosexuales tenían más posibilidades de ser detenidos en los campamentos provisionales y confinados durante más tiempo. Peña concluye que las “miradas fragmentarias tanto de Cuba como de Estados Unidos supusieron verdaderas consecuencias materiales para aquellos a quienes se identificaba como pervertidos”.

Si bien la mayor parte de las investigaciones disponibles se centran en la migración masiva desde Cuba a Estados Unidos —y probablemente ese sea el viaje que la mayoría de los cubanos homosexuales emprendieron—, yo elijo trabajar con material de los archivos peruanos, ya que habla de la mirada del país donde me crie. Perú desempeñó un papel fundamental en la génesis de este acontecimiento, y espero poder trazar una línea que una a los cubanos queer que podrían haberse trasladado a Lima con los temas más amplios que indago a través de mi obra: la inmigración, la memoria y la pérdida dentro de los marcos de la homosexualidad y la intimidad. Como escribe José Esteban Muñoz en Utopía queer. El entonces y allí de la futuridad antinormativa: “Algunas personas dirán que lo único que tenemos son los placeres de este momento, pero no debemos conformarnos nunca con ese movimiento mínimo; tenemos que soñar y actuar placeres nuevos y mejores, otras formas de estar en el mundo, y, básicamente, nuevos mundos”. El concepto de una “construcción queer del mundo” orienta mi práctica y la construcción de estas imágenes.