Collection Connection is a series of personal responses by Museum staff to works in the Frye Art Museum’s collection.

Emil Carlsen. Roses, 1895. Oil on canvas. 35 1/8 x 25 in. Frye Art Museum, Founding Collection, Gift of Charles and Emma Frye, 1952.023

I have a problem with throwing away bouquets once they’ve passed their prime. Usually, it’s a source of embarrassment, especially when others come over and ask why I have a vase full of dead flowers sitting in my kitchen. But that’s less of a problem these days, as I have fewer opportunities to worry about being socially shamed and more time to watch the domestic world’s details unfurl. When someone recently brought us a bouquet from the Pike Place Market, it became a surprising explosion of reds and oranges and yellows every time I walked into our kitchen. A day or two later, while washing the dishes, I noticed the ring of orange petal tulips that had accumulated on the counter. The pink tiger lily’s petals fell around day four or five, its orange stamen releasing the remains of the flower’s pungent scent. When only the papery stems of sea lavender remained, I realized not only that a week had passed, but that the flowers were marking time better than my internal clock seems to be capable of these days.

Still-life works haven’t resonated with me very often in the past. But, as my own life has slowed to a different pace these past few months, I’ve found myself unexpectedly drawn to them. While browsing the Frye’s collection database, I encountered many. The one most familiar to me was American artist Emil Carlsen’s Roses (1895) from the Museum’s Founding Collection. Considered one of the genre’s masters working in the twentieth century, Carlsen was aware of the lack of esteem the French Academy bestowed upon the genre by ranking it the bottom of their subject hierarchy—beneath landscapes, portraiture, history painting, and scenes of everyday life. In 1908, he wrote an article defending its merits, calling still lifes “…the simplest and most thorough way of acquiring all the knowledge of the craft of painting and drawing....” While Carlsen was speaking to the artistic process, I considered whether his observation might also offer a broader perspective—that the still-life genre’s prolonged meditations on domestic objects might inspire a new way to acquire knowledge and understanding of our own lives.

Among the other still lifes in the Frye’s collection, some caught my attention for their timing at transitory moments in the artists’ biographies and careers. I wondered what aspect of familiar still life subjects like flowers and fruits makes them a compelling at moments transition? Pablo Picasso’s Vase de fleurs (1904) was made between the famed Spanish artist’s Blue and Rose Periods, the latter marking his initial formal movements towards abstraction. American painter Marsden Hartley created Still Life (ca. 1915–18) during the years following World War I, when the artist began a transitory lifestyle that lasted two decades, living places as varied as Bermuda; Provincetown, Massachusetts; Ogunquit, Maine; and Taos, New Mexico. Nicolai Fechin painted his vibrant Still Life with Oranges during his first two years in the United States, following his family’s emigration from Russia in 1923, in the wake of the turmoil surrounding the creation of the U.S.S.R.

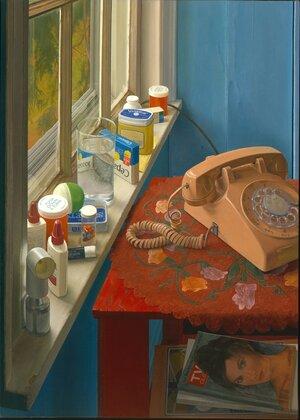

Catherine Murphy. Bedside Still Life, 1982. Oil on canvas. 27 x 19 in. Frye Art Museum, Gift of Howard A. and Judith Tullman, 2001.010

It was in Catherine Murphy’s Bedside Still Life (1982) that I more quickly connected with the role of specificities within still-life works. The American painter’s scene is, for me, as someone who grew up in the 1980s, at once so familiar and so telling. Details like the scraping sound of the rotary phone dial retracting, the oily residue Vaseline leaves on your fingertips, the rustling newsprint of the TV Guide evoke not only my personal experiences from that time, but more poignantly, a nuanced portrait of the era and its surrounding history. Even when we aren’t seeking to engage with these works through questions of form or technique, the power of the still life is still embedded in the details. Their mastery can be found within the seemingly banal object that becomes something more—a potent piece of history often difficult to see as such in the moment, but that acquires layers of meaning that resound over time.

Erin Langner

Exhibitions & Publications Coordinator