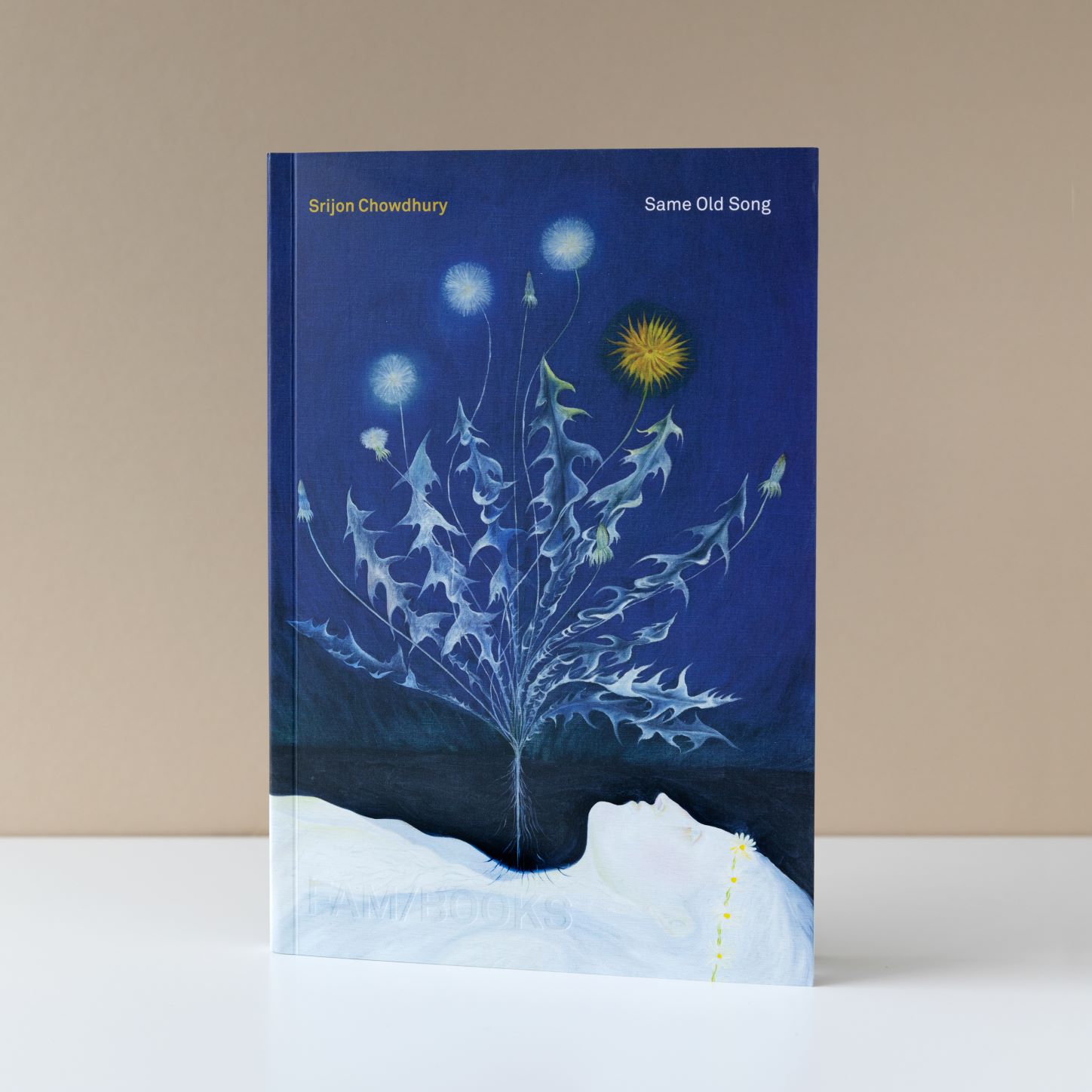

In the following excerpt of an essay from the catalogue Srijon Chowdhury: Same Old Song, the Frye's chief curator Amanda Donnan shares insights into Chowdhury's creative process and the context for the stunning works in the exhibition. Srijon Chowdhury: Same Old Song is on view October 8, 2022–January 15, 2023.

The book includes Donnan's full essay, alongside writings by art historian Mónica Belevan, philosopher SJ Cowan, and color reproductions of Chowdhury's works from 2014 to 2022.

Excerpt from "Introduction / Doors, Portals, Passageways"

by Amanda Donnan

Srijon Chowdhury has been thinking spatially for some time, both within his own art practice and through the process of organizing exhibitions. In 2016, he and his wife, Anna Margaret, established a gallery on their property outside Portland, Oregon—in a large shed adjacent to another that Chowdhury uses as a studio—called Chicken Coop Contemporary. There they have exhibited works by artists such as Katelyn Eichwald, ektor garcia, Andreas Gurewich, Jon Haddock, Harry Gould Harvey IV, Renee Petropoulos, Jesse Stecklow, Pei-Hsuan Wang, and Keith J. Varadi, among others; they have also hosted guest-curated projects and performances. The space is actively occupied by hens, the floor usually covered in hay: an unusual context for art objects even by the standards of Portland’s garage-gallery scene, and one that the artists have often directly engaged. Stecklow, for instance, created an installation called Collection Sites that considered the chickens as the primary audience.

Images: Installation views of Jesse Stecklow: Collection Sites, Chicken Coop Contemporary, Portland, OR, July 22–August 30, 2017. Courtesy of the artist. Photos: Jesse Stecklow

Looking at Chowdhury’s own otherworldly paintings, you might never guess he works in a barn, interrupted by scavenging pigs, chickens, and toddlers, and very much in the stream of earthy, everyday goings-on. Elements of this environment frequently appear in Chowdhury’s paintings, especially Anna and their children, but therein they take on a dreamlike, archetypal quality of being both themselves and more universal representations. Much of art and storytelling can be said to function this way, through an alchemical process of transmuting individual identity into something transcendent, thereby opening portals into other subjectivities. But Chowdhury is particularly concerned with considering the present moment as part of a larger mythology and the potential of art objects—as condensations of desire and mediums of communion—to soften the boundaries around the Self. He describes himself as a “late symbolist,” embracing the imminent epochal change that term implies.

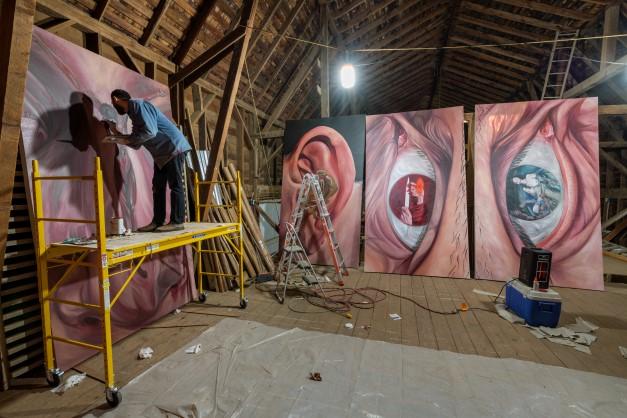

Srijon Chowdhury painting in his studio. Photo: Mario Gallucci

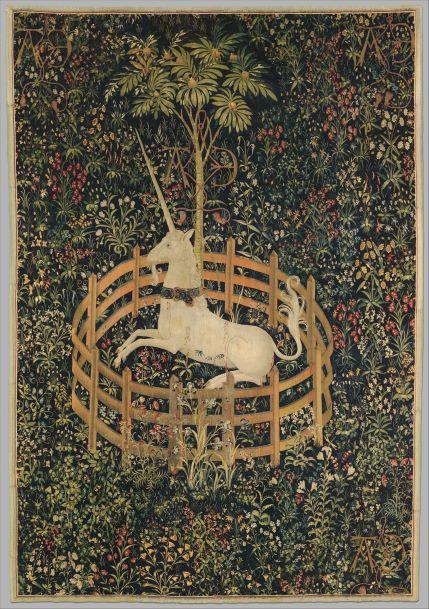

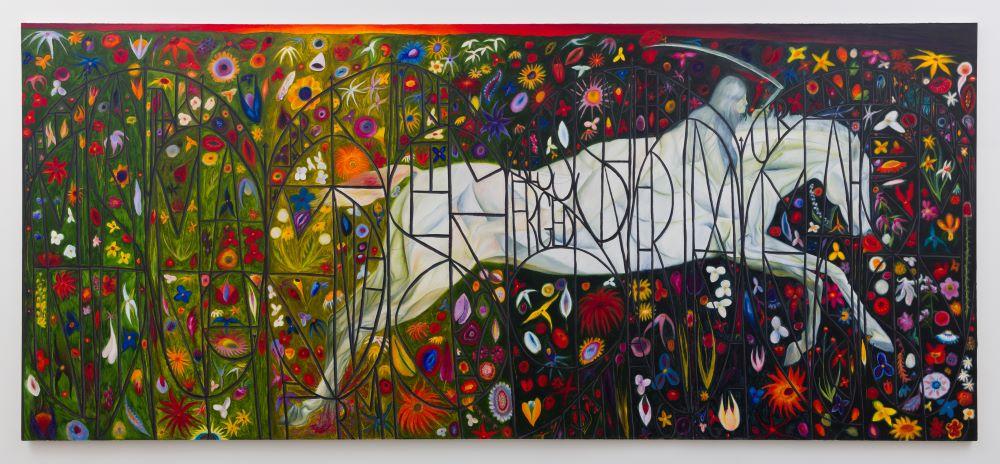

The artist speaks of wanting not only to elicit a reaction from viewers, but of provoking transformation—of transporting them on a visceral and emotional level. One way he has endeavored to do this is by making architecturally scaled, immersive works that he sees as “backdrops to an origin story” of which the viewer is part. The titles of these installations—as in The Garden (2014) and Revelation Theater (2018)—frequently reinforce a connection to Biblical narratives. Meanwhile, motifs like the engulfing floral pattern in works such as Pale Rider (2019) recall Medieval allegories such as the Unicorn Tapestries (1495-1505) that open portals in time to ancient, legendary imaginaries.

Images (clockwise from top left): Srijon Chowdhury. The Garden, 2014. Oil on linen. 96 x 72 in. Installation view from Srijon Chowdhury: The Garden, Klowden Mann, Los Angeles. Courtesy of the artist. Photo: Lee Thompson; Srijon Chowdhury. Installation view of Revelation Theater, The Art Gym, Marylhurst, OR, January 16–March 4, 2018. Photo: Mario Gallucci; Srijon Chowdhury. Pale Rider, 2019. Oil on canvas. 84 x 192 in. Private collection. Photo: Michael Underwood; The Unicorn Rests in a Garden (from the Unicorn Tapestries), 1495–1505. Wool warp with wool, silk, silver, and gilt wefts. 144 7/8 x 99 in. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Gift of John D. Rockefeller Jr., 1937, 37.80.6

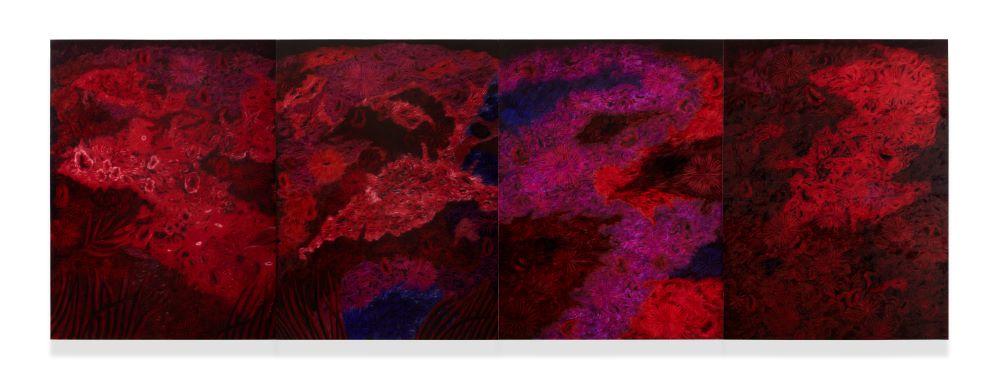

Chowdhury’s more intimately scaled pieces—usually twists on traditional genres like portraiture and the vanitas still life—also emit a potent charge, with saturated colors, deep shadows, and an eerie phosphorescence suggestive of an arcane, supernatural significance. He often references the chakras when speaking about his color choices, especially in relation to the crimson red that recurs like a leitmotif across his practice. In Tantric philosophy and meditation, crimson is the color of the root chakra, which is located at the base of the spine and is associated with grounding or stabilizing energy. For Chowdhury, red is an anchor to this body, this reality, and the beauty of simply being alive despite all that is wrong in the world. But the color has an intensifying effect, too, often declaring that this world is, in fact, on fire.

Srijon Chowdhury. Mouth (Divine Dance), 2022. Oil on Linen. Five panels, 126 x 72 in. each. Courtesy of Ciaccia Levi, Paris-Milan and Foxy Production, New York. Photo: Mario Gallucci

With Same Old Song, Chowdhury pursues an apotheosis of sorts in both subject matter and intended effect. The main gallery contains six enormous new paintings, each of which centers on one sensory organ of the human (inter)face: eyes, ears, nose, and a mouth that is 30 feet long (2022). The central facial feature in each piece acts as a framing device for or composite of smaller images, many of which are sampled from Chowdhury’s previous paintings to convene a retrospective by other means. Though the facial features are modeled on Chowdhury’s and Anna’s attributes, this may be seen as an invitation into the artist’s head and a theatricalization of the imperfect communication process by which an artist encodes meanings for the viewer to interpret. Though these messages may be understood differently by each person, they most importantly signify the effort to bridge individual consciousness and achieve intersubjectivity, maybe even realize interdependency. The notion of a common fate is found within the paintings themselves, for instance in the inferno framed by parted (and seething) lips in Mouth (Divine Dance) (2022). When making this work, Chowdhury was thinking of Auguste Rodin’s Gates of Hell, in which writhing figures representing the whole of humanity emerge from and are subsumed by the same inchoate fluid mass. As in Chowdhury’s installation, Rodin’s massive gates include images that recur elsewhere in his oeuvre, like the archetypal philosopher The Thinker (1904) and lovers in The Kiss (1901–04).