Frye Favorites is a series in which members of the Frye’s staff and community share their perspectives on memorable exhibitions and works from the museum’s collection. This post features Seattle-based artist barry johnson, who reflects on Melon Season (1967), a favorite work from the exhibition Romare Bearden: Abstraction.

barry johnson is a self-taught interdisciplinary creative whose works explore a deep investment in his cultural heritage. His art is created to combat the overarching absence and erasure of Black figures throughout time. Noting how canonical Western history has obscured and annulled Black history, johnson’s work echoes this deletion only to reclaim that very same space. johnson is the recipient of numerous awards, including the Edwin T. Pratt Award, smART Ventures award, and Artist Trust GAP Award.

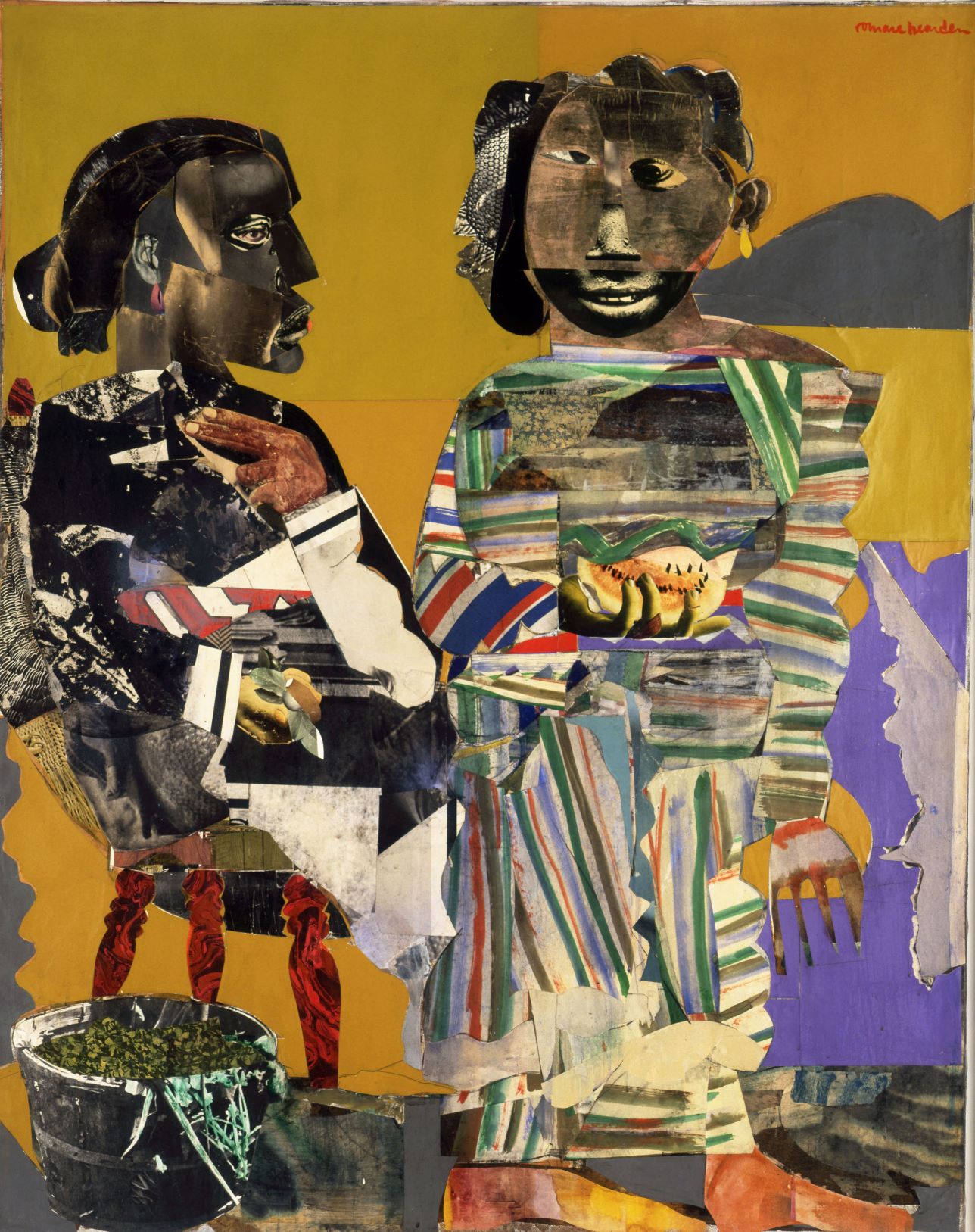

Romare Bearden. Melon Season, 1967. Mixed media on canvas. 56 ½ x 44 ½ in. Collection Neuberger Museum of Art, Purchase College, State University New York, Gift of Roy R. Neuberger, 1976.26.45. © Romare Bearden Foundation / VAGA at Artists Rights Society (ARS), NY. Courtesy American Federation of Arts

“Romare Bearden's work has always been awe-inspiring to me. I'm completely taken aback by his use of color in mixed media. While people may know me as a figurative artist, I really consider myself more of an expressionist working through figures. Early on in my career, I always focused on assemblies of colors and the assembly of elements. I have slowly moved into more portraiture, but in every work that I've created, it's still an assembly of color, an assembly of different elements over portraiture—similar to Romare.

It's particularly Melon Season that I connect with. This work just screams juicy, excellent vibes at me. And I understand also that assembling a work like this is no short feat. It takes a lot to be able to do this. Considering the title, and looking at the posture of the two individuals, I'm sure this deals with the melon trade. And of course, the African history that played within melons—that was one of our first forms of currency. Whenever I see the two individuals sitting there, it really hearkens back to my youth and things that I learned about Blackness growing up in Kansas, and things I learned about how our lives are assembled, unlike other folks. It speaks to the things that we've had to go through to be able to get to where we are now. I always tell people that we are the incarnations of lemons to lemonade. Whenever I look at Romare Bearden's work and see these assemblies, it really makes me think about our existence as Black folks and what we went through and where we at right now and what they were doing at that time. It feels like this assembly of everything.

I first encountered Bearden’s work when I was in college, back in 2007, I want to say at a museum in Kansas. I remember seeing one of his works in-person, and I saw one in a book when I was taking an art theory class. The teacher that I had for my art theory class was very interested in the works of Black artists. I think at that time, most folks were only talking about particular abstractionists, like Jackson Pollock, but they weren't aware of what Romare Bearden was doing. And, while Pollock is also inspiring, whenever I look at works like Bearden's, it hits a lot closer to home, and I see myself reflected in those works.

I’m definitely thinking about scale in Bearden’s works. Scale always plays a part, especially whenever you're using color, particularly when you put bold formats and colors together—these purples, these reds, these greens, the black and white. In my work, I want to lead with a color story. So when I see the sheer scale of Bearden’s works, looking at them in the space now, it's like they just jump off the canvas and scream, "Come inside!" You know what I mean? They're pulling people in, and the color is the real telling of the story there, in terms of the two foregrounded figures and the figure in the back with the melon. I appreciate the power of a small-scale work, but on a larger scale, I think it becomes more of a portal for people to step into. In my practice, I love to work across different mediums. I love to be able to use paint along with additional elements. So when I look at the cutouts that are used and at the assembly of the collage in Melon Season, I appreciate how there's a natural marriage between both mediums that is set perfectly in these compositions.

Installation view of Romare Bearden: Abstraction, Frye Art Museum, Seattle, June 25–September 18, 2022. Photo: Jueqian Fang

You can see a lot of real understanding of art history in Bearden’s works as well. In Melon Season, you have the Cubist elements that Black folks played a part in, as well as the hard breaks away from color. The monochromatic on top of the hard cut edges—it's just such an amazing work. To look at what it took to scale many of these works up, it's just incredible, because the way the color sets next to the cutouts, the figures, the use of all these different mediums coming together within one format. And at that time, doing something that folks knew so little about is a really, really, really big achievement.

It's interesting to think about my eyes sitting in school, looking at this piece when I first encountered it, and then returning to it over time. But considering myself as an artist now, looking at how my works come together, it's played so much of a role. I think that whenever you don't know much about art, your first instinct is to react on how you feel about it. That's the power of art. It's one of those things that emotionally can grab you. But then, when you understand the technical aspects of what it takes to make art, you really come to appreciate it so much more.

I think it's important that institutions like the Frye continue doing this work—highlighting a lot of artists that folks may not know much about. Romare Bearden laid the early groundwork for abstraction along with a few other artists. And I think it's very important that folks come to understand these marginalized, disenfranchised voices that weren't fully recognized while they were living, such as Bearden and the other artists who were part of Spiral. It's such a key time to understand the advancements of BIPOC artists throughout history.”

–barry johnson, artist

(as told to Erin Langner)