This series highlights working artists currently on staff at the Frye Art Museum. The Frye has a wealth of talented Seattle-based artists working under its roof in many different capacities, each with their own dedicated arts practice outside of their work at the museum. Facilitated and written by Alexis L. Silva, Curatorial Assistant, this series is meant to highlight and celebrate these individuals, showcasing their amazing work and arts practices.

Courtesy of the Artist

By Alexis L. Silva

I remember when I first realized I wanted to be involved in the arts. I was about 9 years old, and I begged my mother for a plastic reusable camera from the 99-cent store. She was so reluctant in purchasing it, as she knew I would run through the rolls of film like nobody’s business. Our first-generation immigrant, lower-middle-class lifestyle didn’t have room for an artist in its midst. But she finally caved, and 18 years later, here I am.

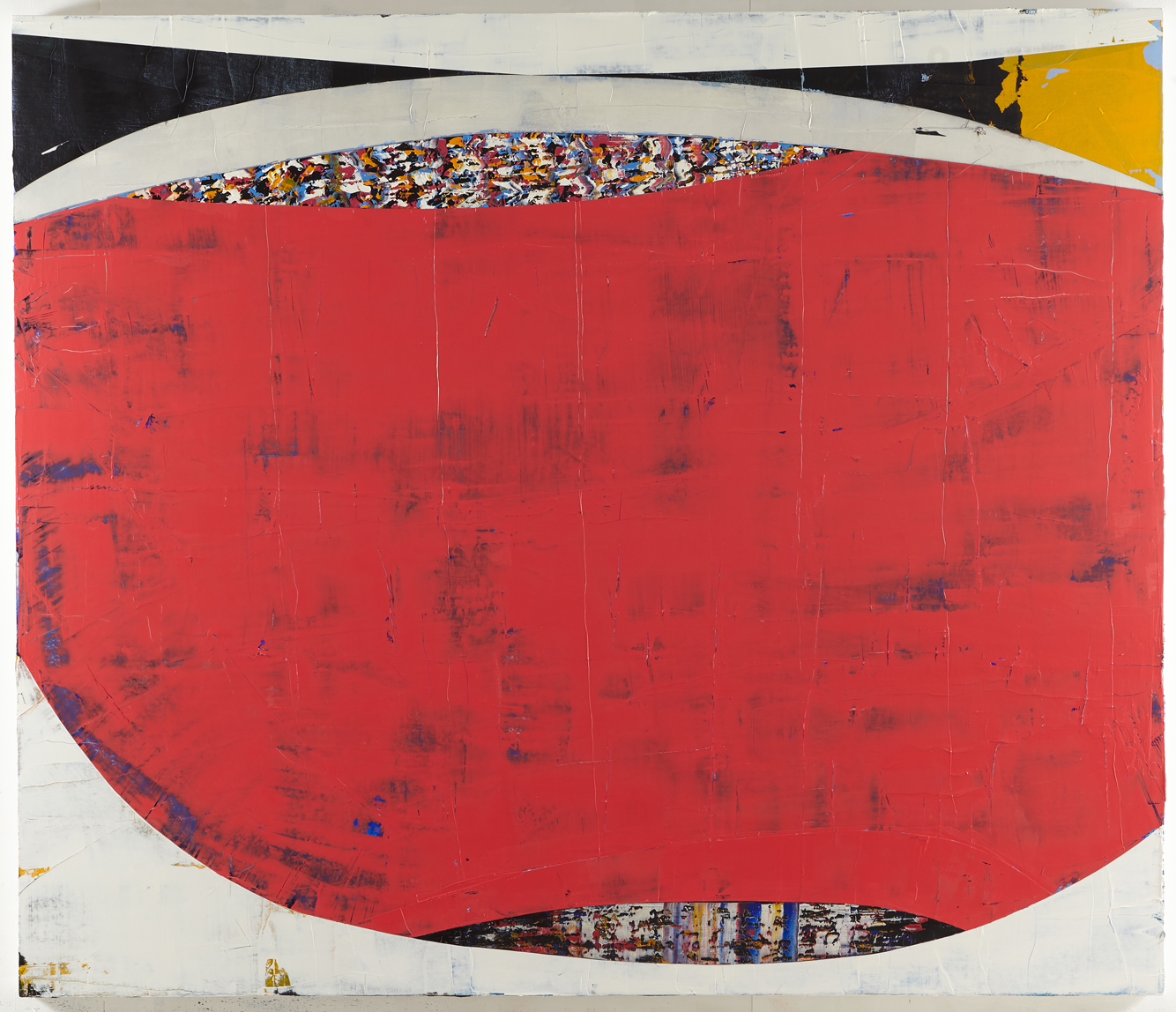

Every artist’s trajectory is different. It starts early or it starts late, it goes on forever or it is short lived. No matter what the road may bring, each experience and practice enriches the art ecosystem in which it exists in. I sat down with Ken Kelly, a local Seattle painter whose presence in the Seattle arts community is not one to be ignored. From winning the Betty Bowen Award and being a finalist for the Neddy Artist Award, to selling out shows in New York and Los Angeles, Ken’s artistic achievements are numerous. You can find his works in local collections such as the Henry Art Gallery, Seattle Art Museum, Tacoma Art Museum, the Microsoft corporate collection, and more. Ken is the Frye’s beloved Lead Preparator and has been with the museum for over 13 years. Getting to chat with him about his practice and life was such an honor—here’s to more Ken Kelly’s in the world!

The following has been edited for length and clarity.

Tell us about your background. Have you always lived in Seattle?

I am originally from Magnolia, Arkansas, and grew up in Georgia and Greenville, Alabama. I went to the University of Georgia where I received my BFA in Drawing and Painting, and then I attended the University of Arizona for my MFA. I hated it so I dropped out and moved to Seattle in 1981. I moved here for a boy, but mostly dropped out of grad school because I realized that it was a dead end. When I moved to Seattle, I was working in an ancient technology known as typesetting. Everybody on the planet can do it now on their personal computer, but at the time, everything printed was typeset. And then, in the mid to late eighties, I got an adjunct teaching job at Cornish College of the Arts teaching drawing and painting. Most places you had to have tenure and you must have an MFA, but Cornish didn’t require it at the time. There was an interim period of several years where I was supporting myself painting, and that was the best job I ever had. That kind of started fading as it tends to do, and I went back to Cornish for another couple of years.

I got started in art handling at Artech and I worked there for probably 10 years. After that, I did freelance and on-call art handling up until taking my current position at the Frye. I've been at the Frye for probably 13 years but was just on-call: I'd be part of the install crew for certain exhibitions and then not be here for months. Between these gigs, selling art, and doing commissions, I was doing quite fine. I was shocked! It worked just fine until it didn't...then the pandemic hit. I was like, "Oh my God, my life is over." But then, all the pieces fell back together, and I was offered a full-time role here at the Frye. It was always a dilemma because, except for that blessed little period there where it was just strictly painting, I've always had to rely on a job, and I've never reconciled having the art life and having money—making a life and the conflicts and time and energy. Ironically, when I went back to it with this position, that's about when I started working on my most recent show, which was in January of last year. That's the fastest I've ever done a show in my life, and I did it all with this fresh new job.

How has your work evolved over the years? Have your influences changed at all?

My work has evolved a lot, and it used to be something I was really self-conscious about. There's this pressure of having to find your thing and do it for the rest of your life. And you have to be consistent with it. Some people kind of evolve, and they may evolve a lot over a long period of time, but it's step by step by step. I tend to just go along and suddenly, off we go into some new thing altogether. I still have mixed feelings about that, but there's something about when you start something completely new from scratch, it's like you're back in art school again and everything's new, and you're discovering stuff and it's exciting. And then after a while I get better at it, and I start knowing things and I start learning little tricks. That's when it just gets bogged down. It's like, "Okay, I'm just doing another Ken Kelly painting and there's plenty of them out there." The imagery may be different, but I always started kind of like [recent Frye artist] Katherine Bradford. One reason I've really responded to her videos and her work is [her approach]: you just walk in there and you start putting paint on [the canvas]. You start seeing what happens, and you react to it, and you change it, and it goes on and on. That's how I got started. Whether it was abstract or figurative, it was the spontaneous, intuitive kind of call and response. That's just how I learned.

Then I reached a brick wall at some point and couldn't figure it out. So, I thought, "Well, let's just do something completely different." And this was a deliberate thing just to shake it up. I started doing stencils and plotting out ahead of time. I'm using a form and I would repeat it over and over, so you have to be kind of systematic. And at first, I was like, "Oh, this is too weird." I wanted a change, but this is a little bit too alien. But it broke the logjam, and for the first time in forever working was easy. That also happened to be that period when I was making a living, because [the paintings] really struck a chord. The work was so heavily based on a really specific, weird, unique technique. I think that's what really attracted people. I just accidentally figured out this process and I just went for it. But there’s only so much that technique allows you to do. So, I tried other things that didn't fit, and it took several years, but it was a gradual process back to just painting and not relying on specific techniques and props.

Your work tends to vary in size. You have these huge, monumental works that are captivating and immersive. Then you have these more intimate personal sizes. Is there any conceptual reasoning behind this?

That’s a really interesting question because I don't know the answer. I think it's a combination of two things. One, my painting teacher when I was in undergraduate school was a total mentor to me. He wasn't just a teacher; he was like my hero. I have always been overly influenced by him. And he did these billboard size paintings. He said he likes huge work and small intimate work; it's the in-between ones that don't make sense. They're not small enough to be intimate, they're not big enough to be exciting. They just look good over a sofa. I worry that maybe that's why I work with two extremes. But I'm naturally oriented towards big work. I like moving the arm. It gives you room to say whatever you're saying. I can't work large all the time, partly because it's just a matter of practicality. Do I really want to devote six straight months of my life working on one painting? Working small, you get to work out more ideas, and they feed each other too. I think a lot of artists will do small work as kind of studies, working up to the big idea. It's always been the opposite for me. I can make the little ones as spinoffs from the big one.

I had a show at 4Culture with these pieces and they were just huge and super thick. It was like these huge paintings that consisted of dozens of little paintings and lots of people commented on that. And I agreed and thought, "Well, let's just do little ones." Complete failure—you can't just separate it and make a free-standing painting. Never worked. Which is how it always is with me. All it is, is a steppingstone to get going. And so those little ones ended up evolving and taking on a life of their own. That's kind of one of the first times I ever created a body of small work that was on its own. And so now I feel like I have these two things going and there have been times where I don't see the connection. The big paintings are doing one thing and the little ones are doing a different thing. Paintings are objects. They're three-dimensional objects that exist on that wall in the same room you're in. But it's also a window. It's a picture. I don't care if you're like a minimalist who just takes a roller and does a solid black canvas. It's still an image. It's a frame that gives you a window into something and it's unavoidable. And I love that. I love the hybridity of it.

Your recent works are these expansive compositions of juxtaposed color and abstraction. Can you walk me through the process of choosing your color palettes along with your choices in form?

The overall blanket answer to that is it’s just totally intuitive. It comes out of somewhere, whatever's going on in the back of my mind. I prefer the mystery of why I choose things and what it's about. But there is a practical level. You walk into the studio, and you got all this stuff, and you make choices. It's not all mystical either. I'm drawn to the colors I'm drawn to because I'm partially colorblind. And I'm proud of it. I'm red-green deficient, which is the most common [type of colorblindness] I can see colors. I mainly have a hard time identifying greens. I'm better with reds than greens. I see things slightly differently and I think I choose these really high-pitched saturated palettes so I can see what registers for me. And it's just more exciting! I'm an abstract formalist. The forms just become these living entities in their own right. And they just have to visually make sense. And since I didn't have anything conceptual to say, well, how do you come up with the form? Where's the reason to do this form as opposed to that form? Rectangles make sense because you're working in a rectangle. But then that got to be a straight jacket after a while. And these forms, in a way, they harp back to the stencil paintings that I was doing because they were all these really sensuous, curved linear compositions. They are also conjuring up landscapes which is a whole new thing for me.

For the first time in probably my whole adult career, I'm tired of my paintings not being about something. I was always Mr. “My paintings aren't saying anything”. And they weren't. And I think that's utterly legitimate. It's not that they have to say something or be about something. They just need to be something. The paintings came first and the interpretation, my own interpretation, comes last. I think a lot of people who think about what artists do, they think it's like, you have these ideas, and you have this stuff you want to say, and so you work out this visual language that will express those ideas. The language came first for me. It's like, what does it look like? Does it work? And if it works, then you go with it. And over the course of time, I can go back and look at my work and start realizing, "Oh, I was dealing with this, or it's saying that about me, or about the world in a kind of indirect way." For a long time, up until doing my last show, I was going through this period of only working because I'm supposed to. My heart wasn’t in it. Now I'm kind of in this place of [thinking] maybe my work should be about something. But I'm never going to turn around and be conceptual, and I'm not going to set up an easel out in the mountains and paint a landscape. It just won't happen. But if my paintings are starting to read like landscapes, and not in a depictive way, obviously, but more like the painting gives me the same sense of excitement and awe that being out in the wilderness for 10 days gives me, I am totally fine with that. I just want to feel the same thing, the same excitement and hopefully make a viewer feel the same through visual cues.

What do you hope your viewer/audience takes from your work and what do you hope they sort of leave behind?

As far as what I hope they take from it, I don't have a preference. That's part of the beauty of it: when I finish a painting and put it out in the world, I've done my part. But it's really not complete until a viewer sees it and reacts to it. The reactions that people have teach me so much. I just want them to feel something, I want them to feel some visual excitement. And I would love for them to love the work and not have any idea why they love it. Just love it. I want them to be as mystified as I am. The other part of your question I really like is, "What do I want them to leave behind? You know, to be honest, I don't have an answer. I’d have to think about that. I always think a nice comment in the book maybe. I always think that a chat is nice. I wish I had my artist statement from my show at 4Culture, I finally managed to write an anti-artist statement that made sense. My work doesn't deal with issues. It doesn't deal with content. My work's basically about nothing, you just stand in front of it, and you see what's happening and go from there. You just fall in love with that. Something like that.

Tell us about your vision for the future of the Seattle Arts community.

That it hangs on and survives. That the rest of the world starts noticing it. That's one thing that's been consistent is nobody in the rest of the country gives a damn. It's really bizarre because there's some incredible artists in Seattle. I'm not saying we want to be art stars—most people [here] don't. Seattle's always had this heavy public art energy. It's got the glass art scene. But I would just like to see it be more dynamic in relation to the rest of the larger art world. We've got artists here who show elsewhere. I mean, I did myself, but nobody comes here to look. Some of the biggest collectors in the world live in Seattle and they've never set foot in a Seattle gallery in their entire life. They have their consultants that buy directly from London and New York, and it's got to be blue chip. Why doesn't somebody pay attention to the great art here and make it blue chip? Some of [the problem] is self-created, because in the real old days, one of my first impressions of Seattle is that "career” was a dirty word. You're not supposed to try for an art career. There's also no writing here. I haven't had a review in 20 years, even though I've had plenty of shows. I know things have gone online, but still not even that hardly gets attention. The mainstream galleries are stuck in their ruts. Then all the cooler galleries are struggling because they don't have any money. They're doing great stuff, but it's not going to get the work out there. I think Seattle is, unfortunately, mid-size. It's not big enough to really get LA or New York energy going. But who knows! In a way, I know less about the art world now than I used to because I'm not as saturated in it. I think that's the function of age in a way. You're just at a different stage in your life.

Where can folks find your work?

I have some works at Studio e, you can also see installation shots of my past exhibition on their website. I have my Instagram which is both art and personal, @mekenkelly6. You can also find some writing on my work on howardhouse.net.