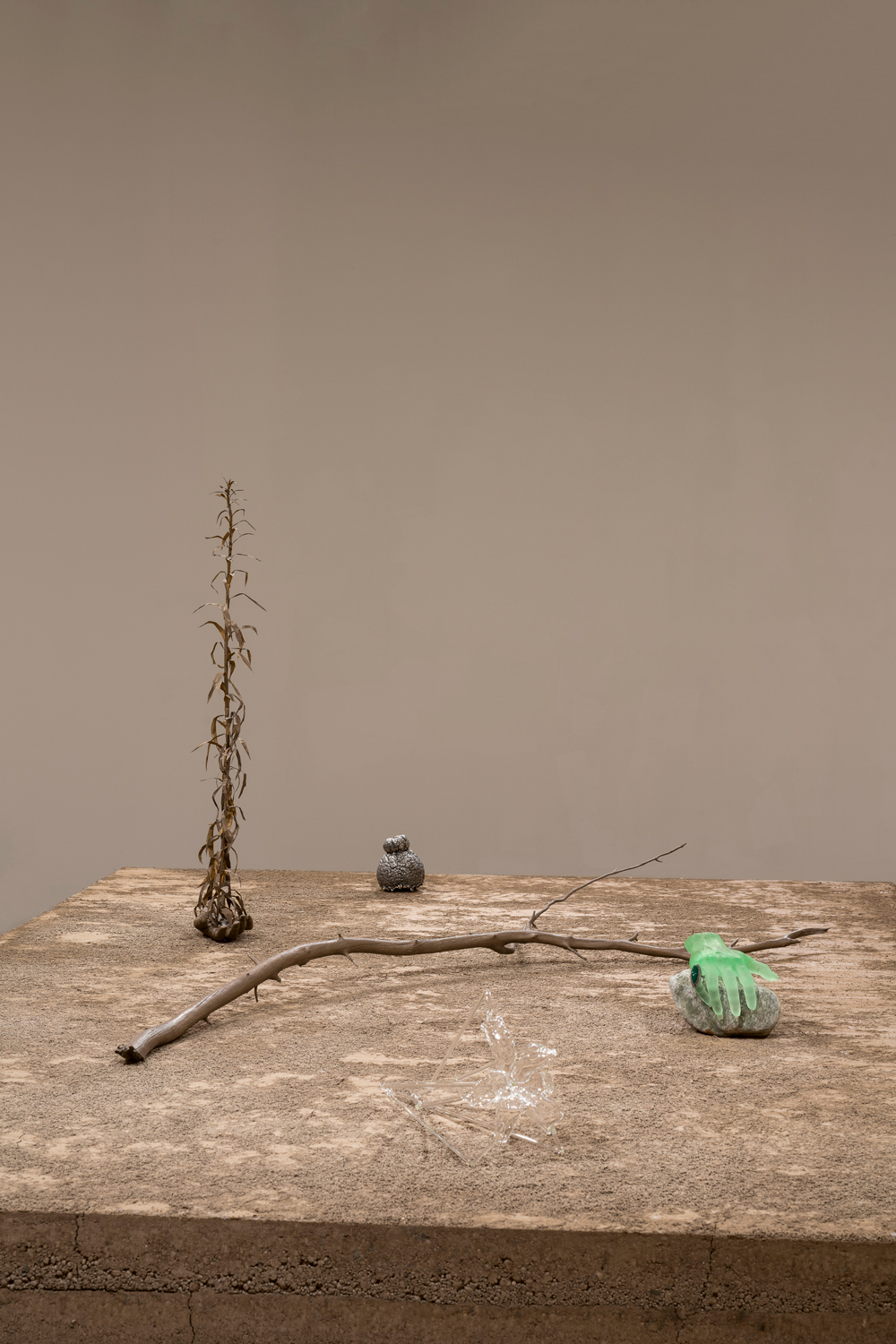

Installation view of Kelly Akashi: Formations, Frye Art Museum, Seattle, June 17–September 3, 2023. Photo: Jueqian Fang

The Poston concentration camp[1], where artist Kelly Akashi’s family was held during World War II, was one of ten sites established by the US government to incarcerate Japanese American civilians following the attack on Pearl Harbor. That the US government incarcerated 126,000 thousand of its own citizens and resident immigrants without due process is now seen as one of the most egregious violations of civil liberties in US history.

Following years of Japanese American organizing and advocacy known as the Redress Movement, the US government offered an official apology and financial compensation to living survivors in 1988. But that wasn’t the end of the story. There are still open wounds, ongoing conversations about the impacts of intergenerational trauma, and social movements like Tsuru for Solidarity that build upon the legacy of resistance that some survivors and descendents see as their inheritance. Organizations like Densho continue to document Japanese American history in all its complexity—and work to ensure that no other group is subjected to this same kind of harm. And, as Akashi’s work demonstrates, many artists, writers, musicians, and other creatives continue to explore this history and its lingering impacts in their creative work.

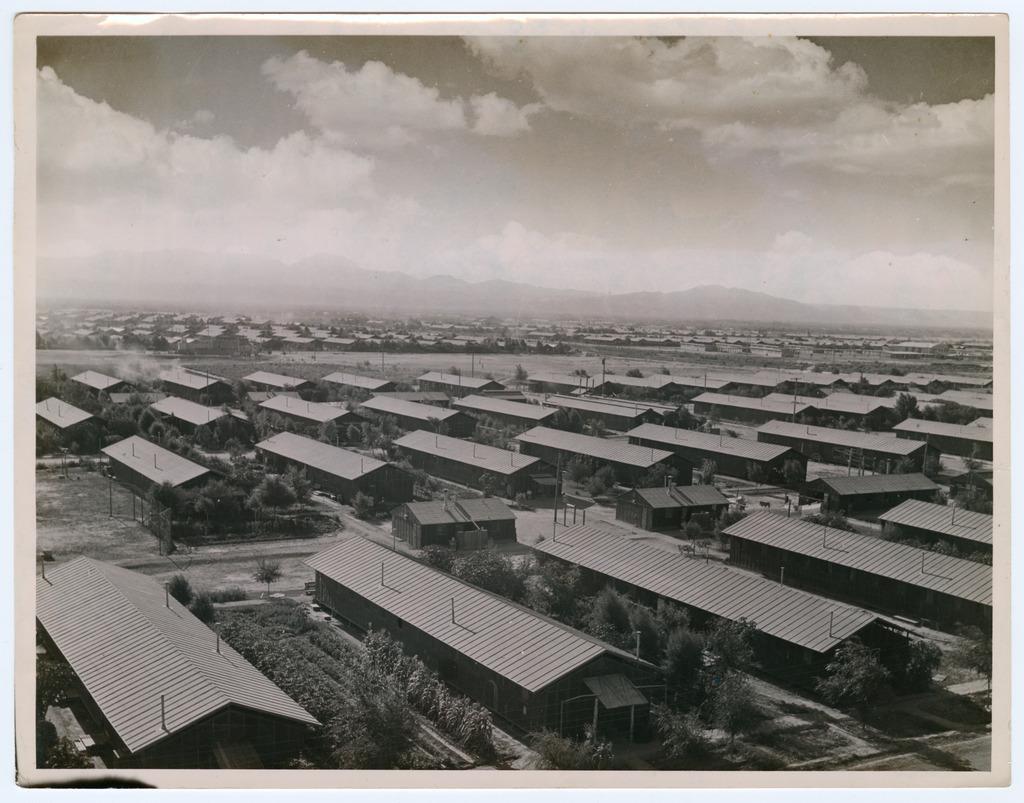

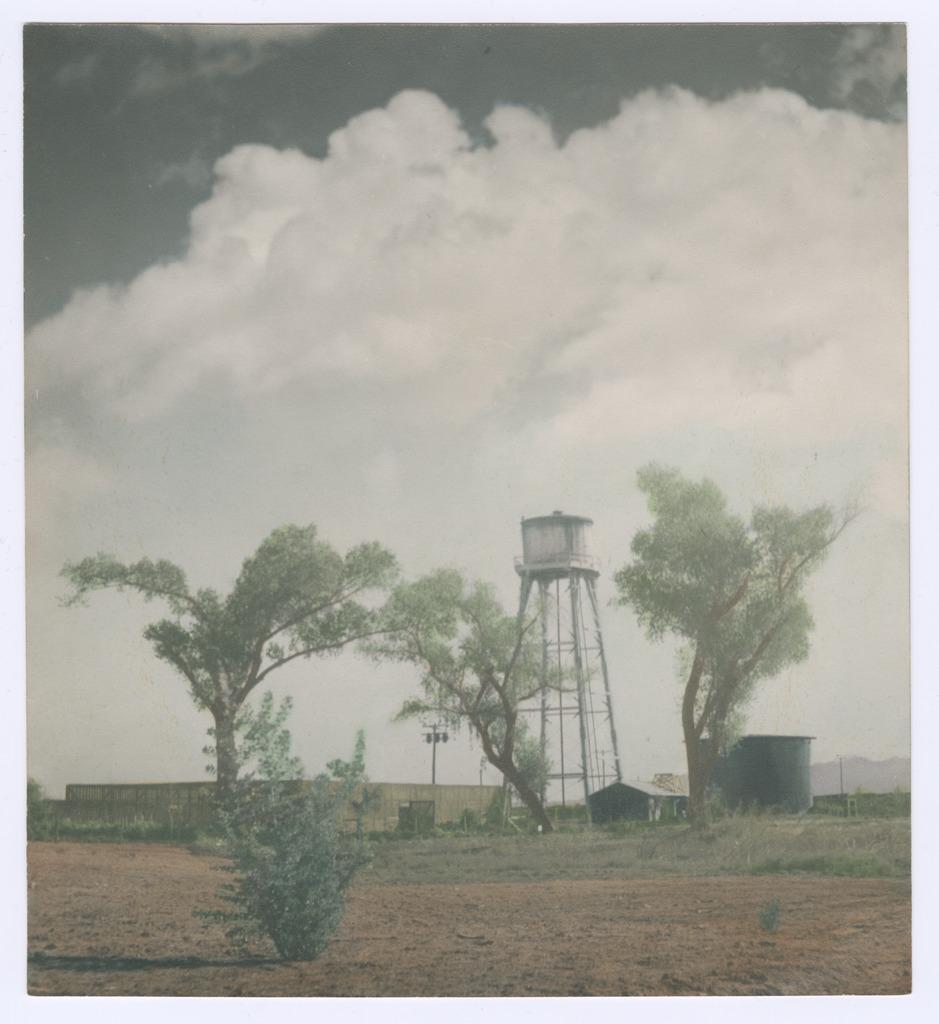

Many of Akashi’s Poston-related works in Formations point to the desert surroundings that incarcerees found themselves living in during WWII. Located in Southern Arizona on the Colorado River Indian Reservation, the environment figured heavily into incarceree accounts of life there.

When inmates began arriving at the height of summer in 1942, they were confronted with extreme heat and dusty conditions. In a July 1942 letter, Pearl Sonoda wrote, "Well, my first impression of Poston was very disappointing since we arrived during a sandstorm. Oh, such dust! I thought I would be buried alive." Hideo Sasaki recalled in a 1943 interview, "When I saw the camp for the first time, it was worse than what I had even dreamed of." In a letter he wrote in August 1942, Sasaki described temperatures "as high as 120 to 130 in the shade, and shades are found only in the barracks or on the side of barracks, there being no trees."

As at other WRA camps, Poston was still very much in the process of being built as the inmates arrived in the summer of 1942. "Mess halls were unfinished, there was lack of refrigeration for meat, plumbing was incomplete, the hospital was not built, there was danger of failure of the water supply and other matters on which life would depend," wrote Alexander Leighton, the head of Poston's Bureau of Sociological Research.

With no clear sense of how long they would be forced to live there, incarcerees did what they could to improve their conditions in the small ways they could. They built furniture out of scrap lumber, added artistic touches to their units, and some even built gardens and fish ponds outside. To alleviate the heat, those who could afford them bought electric coolers, while others improvised. "Men, young and old, stripped down to their shorts, line up at the outside faucet, carrying their cots," wrote Kiyo Sato in her memoir. "Like the rest, I place my cot under the running water and slosh it back and forth to cover the canvas surface. My whole body relaxes with relief as it hits the cool cot."

They also found ways to make their own shade. Many altered their home environments by digging out large cellars so they could stay cool beneath their barracks during the hottest hours of the day, and they altered the natural environment of the camp too. In May of 1944, Community Analyst David French wrote of "the continuing increase in the number and size of trees and other plants" noting that "cottonwoods are reaching a size sufficient to provide real shade." Photographs of the camp show it growing progressively greener over the course of the three years that Japanese Americans were held there. Eight decades later, some of those trees still stand. Akashi photographed and gathered the fallen branches of Poston’s “witness trees”—bronze casts of which can be seen in Formations, on view at the Frye through September 3, 2023.

[1] The term “concentration camp” reflects language used by some officials, including the President, to refer to the wartime incarceration of Japanese Americans. Densho’s use of the term is intended to accurately describe what Japanese Americans were subjected to during WWII, and is not meant to undermine the experiences of Holocaust survivors or to conflate these two histories in any way. Like many Holocaust studies scholars, we believe that “concentration camp” is a euphemism for the Nazi death camps where millions of innocent Jews and other political prisoners were killed. America’s concentration camps were very different from Nazi Germany’s, but they, and dozens more historical and contemporary examples, do have one thing in common: “people in power removed a minority group from the general population and the rest of society let it happen.”

---

By Natasha Varner, Densho Communications and Public Engagement Director and Brian Niiya, Densho Content Director. Densho is a Seattle-based non-profit whose mission is to preserve and share history of the WWII incarceration of Japanese Americans to promote equity and justice today. Learn more at www.densho.org