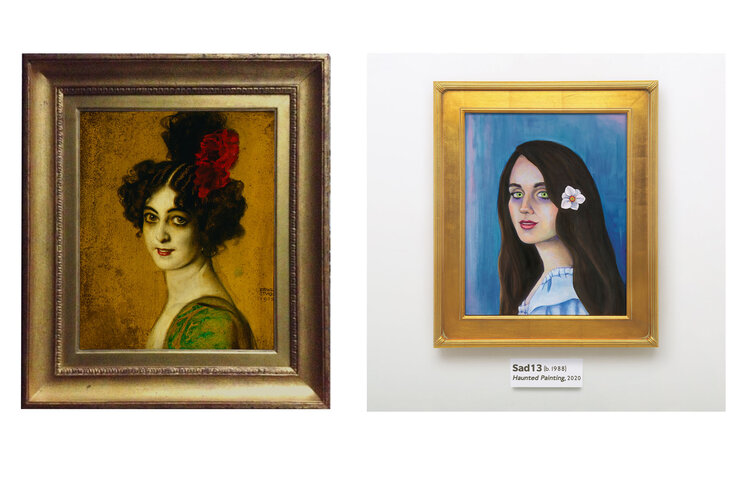

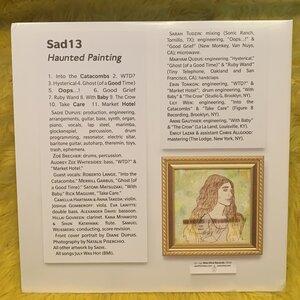

Left: Franz von Stuck. Saharet, 1902. Oil on cardboard. 18¼ x 14½ in. Frye Art Museum, Founding Collection, Gift of Charles and Emma Frye, 1952.164. Right: Sad13. Haunted Painting, 2020. Vinyl record. Cover Art by Diane Dupuis, 2019. Oil on canvas. Courtesy of Wax Nine.

Last year, Philadelphia-based musician Sadie Dupuis came to Seattle looking for ghosts. Unexpectedly, she found some at the Frye Art Museum in the exhibition Unsettling Femininity, particularly in Franz von Stuck’s haunting portrayal of the dancer Saharet. Encountering this painting ended the creative drought Dupuis had been struggling to find her way out of and inspired an entirely new collection of music. The result is Haunted Painting, released about a month ago, which Dupuis recorded through her pop-leaning solo project Sad13 (Dupuis is also part of the rock band Speedy Ortiz). Dupuis wrote all the lyrics and played nearly every instrument you hear on the album, from guitar, bass and synth to the organ, lap steel, marimba, glockenspiel, sitar, autoharp, and theremin. Tackling themes of grief and loss on both a personal and societal scale, from the death of a parent to environmental collapse, the album is littered with ghosts. I reached out to Dupuis to discuss what drew her to Stuck’s portrait of Saharet from the Frye’s Founding Collection and how it influenced the making of her new album.

David Strand: Can you describe your experience of being at the Frye Art Museum and encountering Franz von Stuck’s painting Saharet for the first time? What struck you about this painting? I’m especially curious if any particular details of the painting stood out or stuck with you? How did this experience help spark the making of your new album Haunted Painting?

Sadie Dupuis: I had ghosts on the brain before I even entered the Frye. I was in Seattle for a few days doing a poetry event with Hugo House, who were kind enough to put me up in the Hotel Sorrento a few blocks from you. It's supposedly haunted by the ghost of Alice B. Toklas—which seems improbable, but that didn't stop me and Dorothea Lasky (one of my favorite writers) from staying up late ghost hunting. We did not find Alice or any other ghosts, but I did come to the Frye the next day and was really captivated by that exhibit, especially the Franz von Stuck pieces, which felt ghostly enough.

Stuck’s paintings Die Sünde and Lucifer both are more overtly creepy, but this particular Saharet portrait is less polished (that background seems to have been undone and redone a few times). It feels very alive and in flux and, for that reason, haunting. Stuck exaggerated her features, but if you look at old photographs and other portraits of Saharet, her eyes really were very large and intense in an uncanny way. The way he captured those with such intense shadows focused around and under the eyes, and barely anywhere else, makes it even more eerie. Under-eye circles are beautiful to me, but especially here they evoke exhaustion, relentlessness, secrecy, devotion, grief—any number of traits that could make a person haunted, and I think those themes drove my record.

I also love Stuck's gorgeous gold frames. I am very easily suckered in by gold in art and named the Speedy Ortiz album Foil Deer after another early-twentieth-century piece, Le Cerf by Ossip Zadkine, which I'd seen at the Stedelijk Museum in Amsterdam.

DS: How did Saharet influence the album’s title and cover art? I read in your conversation with Zack Ruskin at the Grammys that your mom painted the portrait on the album’s cover and that it was the first portrait she had made in over ten years due to chronic pain caused by a car accident. Could you talk a little more about your decision to have your mom paint this portrait and what your conversations together were like in crafting this image?

SD: I've always made my own album art, but as soon as I knew this album's title was Haunted Painting, I knew it deserved a cover in tribute to the piece that inspired it, and my portraiture skills just aren't up to snuff. My mom has worked in art as long as I've been alive, and for a long time was a portrait artist. But yeah, she was T-boned by another car over a decade ago which has caused pretty chronic neck pain. She's mostly focused on other subjects and mediums since then because they exacerbate that pain less, so a lot of encaustics and landscape painting focusing on sky, clouds.

We both generally work independently, and so there were a couple of stressful communication moments—she's not used to being art directed, and I'm not used to having anyone interpret my vision for something other than me. But I think it got to a perfect place and I couldn't be happier with the album cover. My favorite detail she added was the poet's narcissus in my hair—perfect for me, a poet doing a self-produced solo record where I played all the instruments. Hah.

Courtesy of Wax Nine.

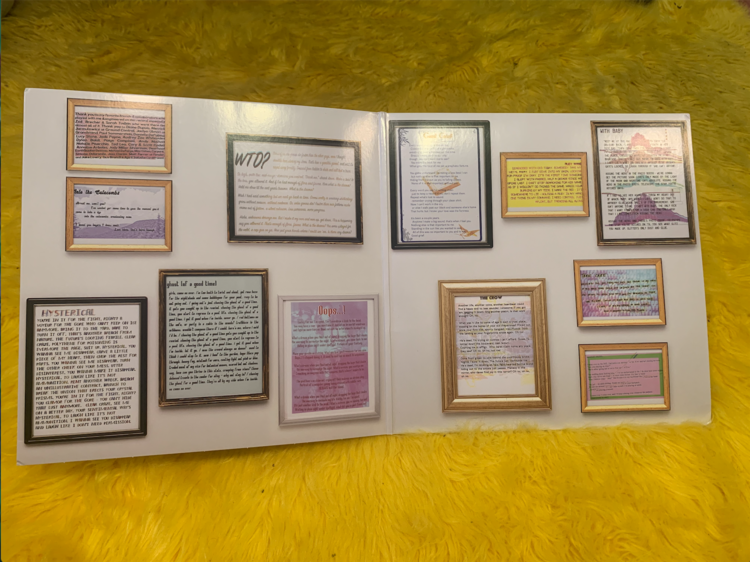

DS: Beyond the cover art, could you talk about the overall album art design? Something I immediately noticed is how much of the album design mimics a museum or gallery environment, with the artworks on the front and back covers in gilded frames with labels underneath them (a nice touch). Even the song lyrics each have their own frame, too.

SD: Thank you! I was thinking of other album covers I love that feature a painted portrait of the recording artist—Joanna Newsom's Ys, Lorde's Melodrama, a really great recent one of Torres painted by Jenna Gribbon (although actually, I think that came out after we were already working on this one). But my relationship with the Stuck piece was about coming upon it unexpectedly in an exhibit, and I wanted to recreate that for anyone who encounters an LP rather than just use a portrait out of context.

So, the conceit was to set the whole thing up like a gallery wall, and put the recording and performance credits on placards like a description of the exhibit. The back cover has a self-portrait of me, which I did on linen with acrylic paint and embroidery floss. I've worked with thread in all my album covers since Speedy Ortiz's Major Arcana, and there are several artists I really admire who incorporate fibers into their work, often to political ends—Inge Jacobson, Lauren DeCioccio, Izziyana Suhaimi, Christa Maiwald, and lately I've especially loved Erin M. Riley.

And then as you noted I did the lyrics as its own "exhibit" of text art. As a poet concerned with how words appear on the page, I'm always trying to figure out a way to give the lyrics a good visual representation. I love Jenny Holzer, Barbara Kruger, Ed Ruscha, and many artists who work with text and typefaces. So I tried to do risograph-inspired work on an inkjet printer, so basically printing color layers separately, sometimes feeding one color layer through the printer a few times, giving it that offset look. It was a pretty good and engrossing project to work on in the first month of quarantine, I have to say!

DS: A central theme of the exhibition Unsettling Femininity—that Saharet is included within—is confronting the male gaze in the tradition of Western Art that continually objectifies women. It is interesting to think about Stuck’s painting of Saharet, who was a famous Australian dancer and performer back in the beginning of the twentieth century, within this tradition while interpreting Saharet as a ghostly figure as you’ve mentioned previously. As a last, rather speculative question, who or what do you think Saharet might be haunting through this painting?

SD: I hadn't heard of Saharet when I first saw this portrait and identified it as "ghostly" or "mysterious." A lot of her fascinating life (extremely well documented at a blog called Forgotten Australian Actors) is indeed a mystery, and kind of a rabbit hole. I'll do my best to summarize succinctly.

Saharet's mother, prior to her birth, changed her own name and backstory at least five times, likely to conceal her Chinese heritage in racist Melbourne. Her third daughter, born Paulina Clarissa Molony, became involved in dance and theater before moving to San Francisco at age thirteen, probably alongside her mother. She'd already gone through a few name changes before choosing Saharet, after which she quickly became world-celebrated, a progenitor of the modern dance movement whose high kick and gymnast moves were especially renowned. In 1896, at age 18, she married a German-born New Yorker named Ike Rose (also an assumed name!), who became her manager and the father of their daughter Carrie. Rose intentionally circulated conflicting stories about Saharet's origins to generate intrigue, possibly also to shield her from racism. Saharet herself was seldom interviewed, even as she became a theater and film star across Europe—around which time she sat for at least three portraits by Stuck, as well as some by Maurice Biais, Leo Rauth, Franz von Lenbach, probably many more. There's a lot more to her story, including some high-profile remarriages and affairs, and ultimately the tragic death of her daughter by suicide (likely also how Saharet died in 1964), but that all came after Stuck's portrait.

It would be a stretch to say I intuited any of this very involved backstory from the portrait, but I did get a sense of secrecy, grief, and obsession, and at the time Stuck painted her, it's easy to speculate that Saharet was sitting on all those feelings. She had risen to unimaginable fame and success for her innovative dancing, all the while keeping obscured the truths of her life and seemingly destitute childhood. Her 10-year-old daughter, who'd previously traveled on tour with her parents, had just been sent to a convent school in Belgium. Perhaps Saharet maintained a sense of control and power with this secrecy, but I can't imagine the stress of keeping so much of your life hidden, and I do think that comes through in Stuck's portrait, and probably in her dancing.

My mom didn't know anything about Saharet's history when she agreed to do this painting in tribute. But she did tell me that the photos of me I sent her for reference wouldn't work. I'm paraphrasing, but she said something like, "Your smile and eyes need to guard a secret. That's what makes Stuck's painting interesting."

You can purchase and stream Haunted Painting by Sad13 via Bandcamp or on other streaming platforms, and see Saharet by Franz von Stuck in Unsettling Femininity: Selections from the Frye Art Museum Collection through May 30, 2021.

David Strand

Associate Curator