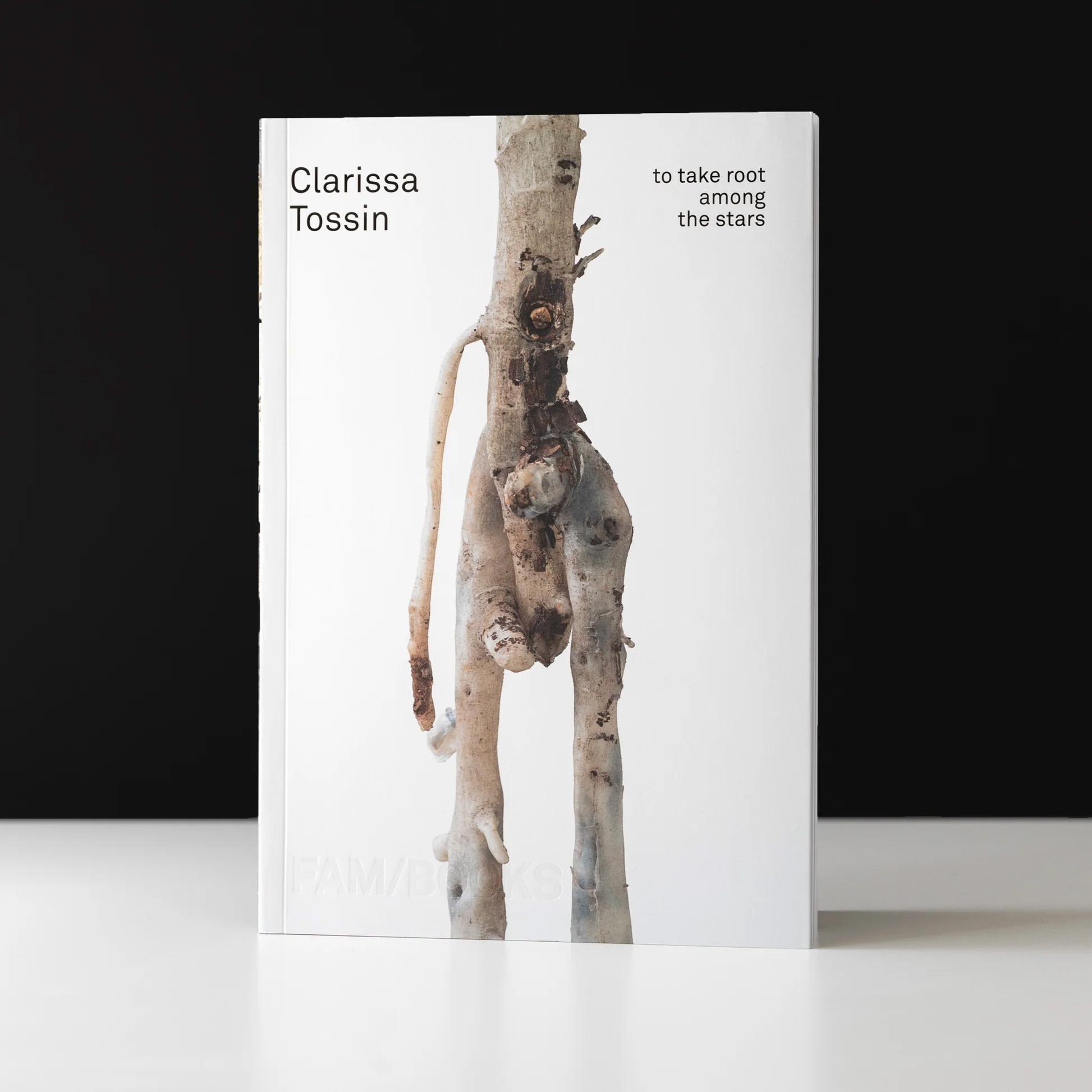

In the following excerpt of an essay from the catalogue Clarissa Tossin: to take root among the stars, the Frye's associate curator Georgia Erger shares insights into the urgent context for this exhibition, which is on view October 7, 2023–January 7, 2024.

The book includes Erger's full essay, writings by art historian Leslie Dick and curator Vic Brooks, and color reproductions of Tossin's works from 2008 to 2023.

Excerpt from "Encounter Zones"

by Georgia Erger

The black and beige waters of the Negro and Amazon rivers meet but do not mix at Brazil’s Port of Manaus, a site of multifaceted ecological, cultural, and economic confluence in the heart of the Amazon rainforest. Global industries that have developed in the region and local Indigenous communities alike rely on the rivers and forests for survival. Manaus was declared a Free Trade Zone in 1967; consequently, tons of electronic and organic goods are manufactured and exported downstream for international consumption. Meanwhile, local communities contend with the ruinous effects of extractive capitalism while continuing to maintain and develop cultural traditions, as they have since the region was first colonized at the turn of the sixteenth century.

The late nineteenth-century demand for rubber turned Manaus into the most industrialized city in Brazil until 1912, when the British Empire assumed control of the world market by creating rubber plantations in its colonies in Southeast Asia and Africa. In the 1930s, Henry Ford purchased land in the interior of the rainforest with significant tax breaks and established industry towns to harvest latex from rubber trees to produce automobile tires. These industrial outposts in the Amazon exemplify how colonial frontiers function as encounter zones between foreign capital and nature, wherein nature is not only destroyed, but put to work, as cheaply as possible. As Raj Patel and Jason Moore succinctly state in A History of the World in Seven Cheap Things: “Capitalism not only has frontiers; it exists only through frontiers.”

This long history of the Amazon and its meanings in the popular imagination have led to the present, where the playful yet jarringly dislocated name of the Seattle-based company looms large. The name also well-represents artist Clarissa Tossin’s sustained, nuanced explorations of the intersections and geopolitical causes of climate change and capitalism’s frontier mythologies. Tossin, who was born in Porto Alegre, raised in Brasília, and is now based in Los Angeles, first began repurposing Amazon delivery boxes as sculptural material while investigating colonial histories of—and resistance to—exploitative natural resource extraction in Manaus. Her sculptural work, Nova gramática de formas #2 (New Grammar of Forms #2) (2018), for example, features terracotta replicas of electronics cradled in baskets woven from strips of recycled Amazon delivery boxes and satellite images of the Negro and Amazon rivers. Tossin found inspiration in Amazonian basket-making traditions to devise her paper-weaving technique (see above). The laborious weaving process disrupts associations of expeditious commodity chains conjured by the immediately recognizable barcodes and smiling arrow logos of the Amazon boxes. Tossin is mining overlooked frontiers of cultural knowledge to present potential futures that could reconcile, or survive, capitalist-driven ecological destruction.

Tossin’s use of Amazon boxes—ubiquitous detritus of our rampant consumerist culture—points to our simultaneously significant and insignificant role in climate change, and to the overwhelming scale of the crisis itself. Climate change is so massively distributed in time and space that we can see only pieces of it (the single cardboard box delivered overnight to our doorstep, for example) at once. Further, much of our anxiety about a climate apocalypse stems from our inability to identify whether it is imminent or if we have already reached that terrifying frontier, as Timothy Morton discusses in Hyperobjects: Philosophy and Ecology after the End of the World.

Tossin troubles capitalism’s unwavering faith in progress, a culturally situated “way of knowing,” and instead engages ideas of difference and repetition, cycles and transformation, and circular time. Clarissa Tossin: to take root among the stars brings together works across media from the last decade of Tossin’s practice, including newly commissioned weavings and drawings, to speculate on uncertain futures and networks of interconnectedness across time and geographies.

The exhibition begins with the translucent corporeal form of a deceased tree. Hanging upside down in the Frye Art Museum’s rotunda, Rising Temperature Casualty (Prunus persica, home garden, Los Angeles) (2022) is a silicone cast of a peach tree from the artist’s garden that perished due to heatwaves and drought in Los Angeles. The subtitle of the artwork serves to indexically archive the consequences of climate change; however, this rational, scientific treatment is betrayed by the ghostly, skinlike materiality of the sculpture, which viscerally points to the fragility of life on our planet. The silicone cast retains bark from the imprinted tree. This seamless melding of synthetic and organic materials is prevalent across Tossin’s practice and embodies the tension between extractive approaches to Earth’s natural resources and Indigenous ways of knowing and being in reciprocity with the land.

Rising Temperature Casualty, and the death it memorializes, points to how climate apocalypse might not be a single event, but a series of seemingly insignificant, intimate, interconnected moments that unfold right outside our back door. As Timothy Morton states: “The end of the world is not a sudden punctuation point, but rather it is a matter of deep time. Twenty-four thousand years into the future, no one will be related to me. Yet everything will be influenced by the tiniest decisions I make right now.” While Morton directly implicates us, Tossin more subtly identifies endemic exhaustion—of natural, physical, and emotional resources—across “deep time.” And indeed, the limply hanging branches of the cast tree physically express this sense of depletion and ephemerality.

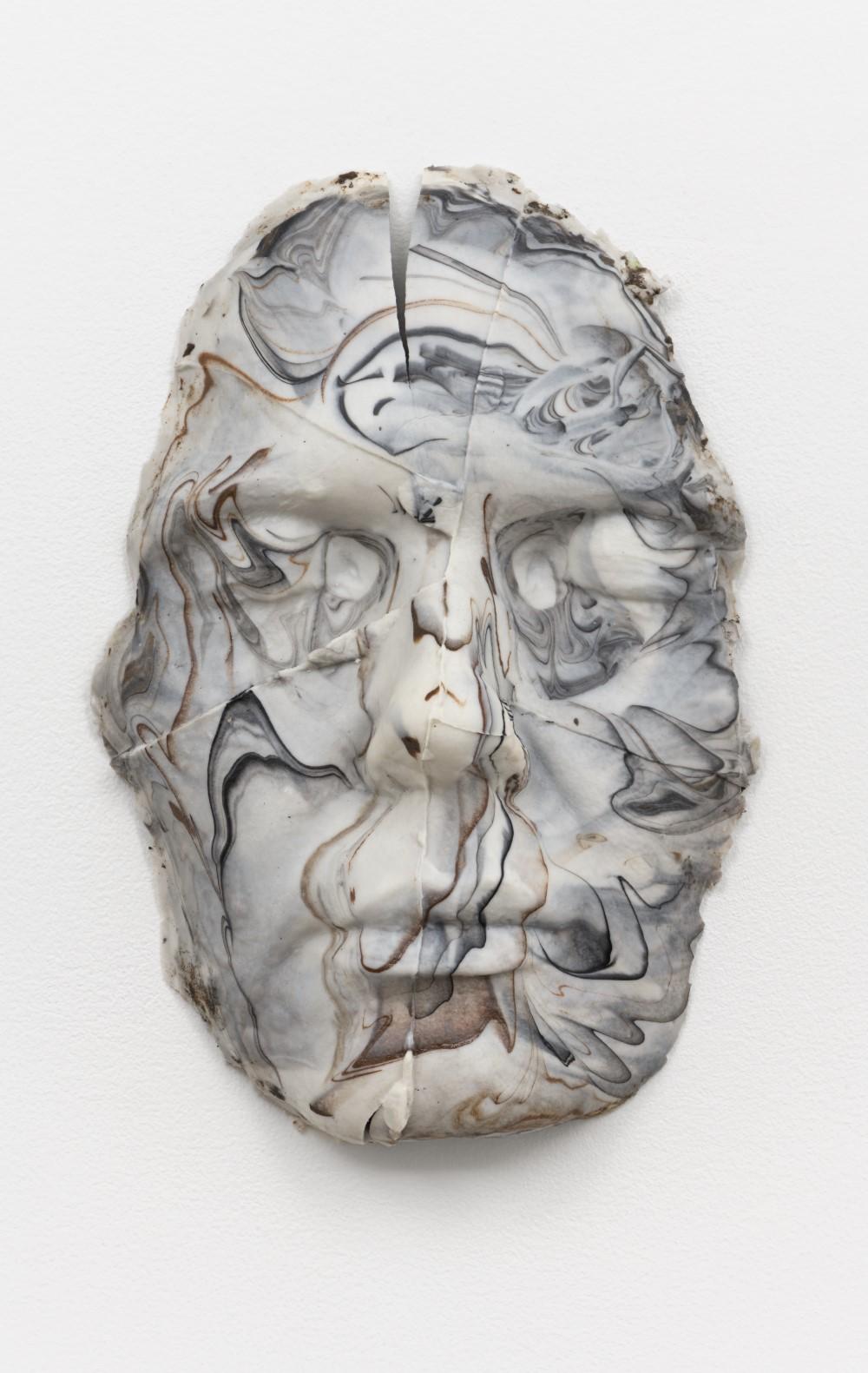

A series of clay imprints, Becoming Mineral (2021) capture Tossin’s face, eyes closed and in a state of partial disappearance. They evoke death masks, or “memento mori,” and “grapple with the death of a certain way of being human, a certain way of inhabiting this planet, a certain way of being a collective body that’s now being put into question due to technological advances,” the artist said in an interview with Sandrine Wymann. The masks were made during the pandemic lockdown with leftover clay from the artist’s studio; the striking marbling effect reflects the haphazard combination of different-toned clays, including porcelain. Tossin consistently uses recycled and waste materials in her sculptures and of her motives states, “I’m very interested in the idea of degrowth, and lowing down the hectic cycles of production and consumption. My own pressing dilemma is: How do I maintain a sustainable art practice aligned with degrowth ideas, while also engaging in material production?”

If not a solution to this dilemma per se, Future Fossil (2018), a melted composite of the artist’s own plastic waste, reflects our contradictory relationship with the environment. Tossin’s imagined “core sample” of a future geological record is preserved for a speculative, even post-human landscape. Composed of melted plastics, electronic waste (a bundle of wires hangs from the end of the sample), silicone, plaster, cement, and organic matter, and embedded in a fallen cedar tree trunk, this twenty-foot “future fossil” visualizes the entanglement of human consumption and the environments that necessarily adapt and react to our overwhelming presence. The future geological strata of our present era, alternatively dubbed the Anthropocene, Capitalocene, or Wastocene, as Jason Moore notes in Anthropocene or Capitalocene? Nature, History, and the Crisis of Capitalism, will no doubt include layers of manmade “minerals” and materials such as concrete and plastic. Tossin describes Future Fossil as sprinkled with sci-fi content in an interview with Meg Rotzel. Indeed, the sculpture can be interpreted as a fictionalized readymade: found, incidentally aesthetic, neither industrially manufactured nor geologically created. The swirling colors of the composite core set this “sample” apart from the familiar visual language of fossils, but the materiality of plastic—bright, cheap, sterile—is deeply integrated into the cultural imagination of advanced capitalist societies. It is therefore darkly humorous, or perhaps wonderfully optimistic, to imagine a future in which plastic might be unfamiliar.