Some recollections of moving through the physical space of the Museum from Unsettling Femininity guest curator Naomi Hume.

Unsettling Femininity: Selections from the Frye Art Museum Collection, installation view, September 21, 2019—May 30, 2021. Photo: Jueqian Fang

All the paintings on the west walls of Unsettling Femininity depict children! I came to this realization during the installation of the exhibition in September 2019. I’d been planning the exhibition for over a year, working on it on and off, mostly from my office at Seattle University, just a few blocks from the museum. I had visited the Frye Salon exhibition multiple times to see works from the Founding Collection as I considered which to include in Unsettling Femininity. I had also gone in a few times to move tiny reproductions of paintings around the scale model of the galleries that the Frye keeps in their storage space, trying out different arrangements of the artworks I’d chosen for the show.

But it wasn’t until the paintings were actually hanging in the galleries that I noticed one wall included only images of children: Mary Cassatt’s pastel of a young child turning towards the viewer (Little Eve, ca. 1902); the two tiny paintings of children striking poses for each other on the seashore by Ludwig von Zumbusch (At the Beach, ca. 1904-5, and Children by the Sea, n.d.); Franz von Lenbach’s two paintings of his daughter, Marion, at about ages three and eight (Marion Lenbach, ca. 1895 and Marion Lenbach and the Daughter of the Painter Nikolaus Gysis, 1899); and finally, the child-cupid, blowing a bubble while looking out at us with unaccountable seriousness, from the background of Gabriel von Max’s enigmatic Soap Bubbles (1881).

I hadn’t planned a wall of children while working on the exhibition, but somehow, they all ended up aligned, though separated by dividers into three differently-themed spaces in the show. The children matter to the exhibition; their playacting brings out the performativity of gender that is the show’s central theme. But, their role doesn’t require them to congregate on a single wall. I liked that they did, though—when I walked through the rooms and sensed them all on my left, as I physically turned my body in each themed gallery and saw them there. I miss that physical experience of the museum: walking and turning and feeling the paintings as real objects on the wall, in the room, with me. I miss the way moving through a museum—bodily compiling new sequences and juxtapositions of pictures—can produce little epiphanies like that.

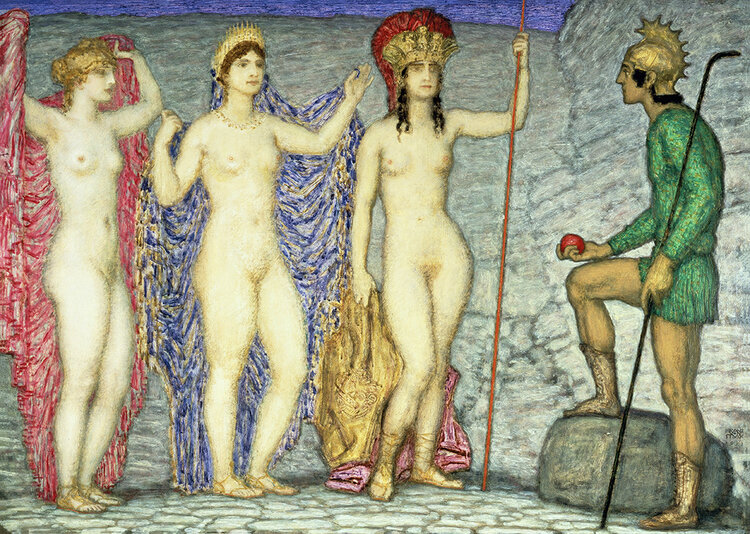

When I give gallery tours of Unsettling Femininity, I emphasize the way moving through space in the museum produces different lines of sight or new connections between artworks. I always begin with Franz von Stuck’s The Judgment of Paris (1923). I ask visitors to look closely at the painting, to examine how Stuck puts the three goddesses in the painting on passive display while he activates Paris, the judging male character in the painting.

Franz von Stuck. Urteil des Paris (The Judgment of Paris), 1923. Oil on panel. Frye Art Museum, Founding Collection, Gift of Charles and Emma Frye, 1952.168

Stuck poses Paris in profile, highlighting the activity of looking: the judging shepherd raises and bends one leg, resting his foot on a rock. It’s a static step, but it activates Paris. Stuck stills the goddesses, though—they stand in a line, nearly parallel with the rock wall behind them. Athena, goddess of wisdom, with her staff, stands parallel to the wall and fully faces the viewer, a position that stills her completely. Hera, in her tiara and necklace, and golden-haired Aphrodite arrange themselves around the axis of Paris’s perspective; each holds up her cloak behind her, framing herself as a static image within the painting. It’s a clever, subtle composition that emphasizes the gaze itself as an action and the male figure as central, despite the painting’s clear function as a vehicle to showcase the nude female body.

I then ask the visitors to back up, to view the exhibition from the wall opposite the entrance. As we move our bodies in space, three paintings of nude women resolve themselves into a line. Gustav Meyer’s Stella (1889) and Lilian Genth’s Sun Maiden (ca. 1909) hang on either side of a doorway that frames Franz von Winterhalter’s Susanna and the Elders (1866) in the next room. We actively move our bodies to produce the line-up of painted bodies arranged before us, a view that I hope reminds visitors of the three goddesses on display for Paris.

Installation view of Unsettling Femininity: Selections from the Frye Art Museum Collection, Frye Art Museum, September 21, 2019—May 30, 2021. Photo: Jueqian Fang

It feels surprising when we move our bodies this way and the paintings fall into line. We are now standing before three nude women and I ask everyone to think about our roles as viewers of paintings, of paintings of women, of women themselves. Do we have to become judges? Is that the default? Just because the exhibition layout puts us in the position of Paris, do we have to do what he does? Do the paintings themselves, individually, position us as judges? Can we look at the paintings without taking on the assumptions implied by the painter, the stance the painter assumed the viewer would take?

The unspoken assumption in nineteenth-century Europe was that the viewer of paintings who mattered was white, male, and powerful; painters constructed their images to appeal to this imagined viewer. No matter our actual identities, this is the viewing position most of the paintings in Unsettling Femininity offer the viewer. The paintings that open the show display women as vulnerable and available, offering an experience of power to the viewer, but that position is hard to inhabit unless the viewer recognizes it as such. The paintings in the show were made during a historical moment that insisted on a strictly binary understanding of gender with clear implications of relative power. Perhaps the broader understanding of a continuum of gender identities in our own time makes it possible to question the powerless position imposed on women in so many nineteenth- and twentieth-century paintings. When we move through museum spaces and see visual objects shift in relation to each other and to our own bodies, we reproduce the power relations between an active, looking, and thinking person and a passive, visual object on display. Walking through Unsettling Femininity, we make this relationship between viewer and artwork concrete. I hope the experience prompts us to challenge pictures that continue to reinforce harmful fictions: that gender is binary and that one gender identity must act and wield power while another must passively submit. Most of all, I hope the unsettling paintings in the show help us question the pretense that these gender relations are natural and inevitable in the real world.

Naomi Hume

Guest Curator, Unsettling Femininity