This post provides an overview of the exhibition Human Nature, Animal Culture: Selections from the Frye Art Museum Collection, on view June 12, 2021 - August 21, 2022, using the introduction, section overviews, and label texts included in the exhibition.

Installation view: Jueqian Fang

Introduction

Reason, science, and culture supposedly elevate humans above nature, yet many of our species’ greatest achievements would not have been possible without animals. They have nourished our bodies, carried our belongings, and become our closest companions, helping humans to create the world as we know it. But too often we take animals for granted. Now, as we confront climate change and mass extinction, humankind is forced to reexamine how we affect animals and the natural world. While we turn to science for solutions to address this crisis, we can look to art to understand our past, present, and future relationships with our fellow creatures.

The many paintings of animals—especially domesticated animals such as cattle, sheep, pigs, dogs, horses, and fowl—in the Frye Art Museum’s collection offer a unique opportunity to examine human-animal interactions during the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries in parts of Europe and the United States. Beyond appearing as subjects in many of the paintings collected by the Museum’s founders, Charles and Emma Frye, domesticated animals were critical to the formation of the Museum itself. Charles Frye, raised on an Iowa farm, built a successful meatpacking business in Seattle after arriving in 1888, and this business in turn provided him with the means to begin collecting art. Presenting works from the collection as well as archival materials that illuminate the Fryes’ history in the meatpacking industry, this exhibition considers the various forms of labor domesticated animals perform and their significance as deeply ingrained elements of human society.

Imagery of domesticated animals provides a fruitful starting point for reevaluating the roles animals have played in our lives. Paintings of animals became especially popular with artists and collectors during the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, when spreading industrialization and population shifts from rural to urban settings reduced opportunities for close contact with animals. People increasingly engaged with animals in mediated ways—by means of images. Paintings in particular created—and continue to create—a realm where relationships with animals are negotiated and take shape beyond the confines of language and the demands of reason. Reconsidering our long, often fraught relationships with domesticated animals reminds us that humans are closer to animals and animals are far closer to culture than we often care to think.

Human Nature, Animal Culture: Selections from the Frye Art Museum Collection is guest curated by Kathleen Chapman, Associate Professor of Art History, Virginia Commonwealth University. Generous support is provided by the Frye Foundation and Frye Members. News media sponsorship is provided by The Seattle Times. Broadcast media sponsorship is provided by KCTS 9.

Section Navigation

Landscape Painting and Animals / Animal as Subject / Animal Labor / Animal Culture

Installation view: Jueqian Fang

Landscape Painting and Animals

Over the course of the nineteenth century in Europe and the United States, the environmental impacts of modernization and industrialization became undeniably visible. Cities and their environs encroached steadily upon untouched wilderness, while manufacturing and housing subsumed land long used for agriculture. As animals vanished from people’s daily lives, land untainted by human modifications began to disappear too. In art and literature, the dwindling of the natural world prompted a new sensitivity to the powers of nature. Landscape painting, and eventually representations of animals, acquired more urgent significance.

In contrast to the portrayals of untamed nature also popular during this period, the works in this section reflect painterly explorations of a natural world that has been altered by humans. While the term “domestication” is typically used to describe the taming and modification of animals for human use, it can also be applied to plant life. These harmonious scenes seamlessly integrate domesticated landscapes and animals. They present nature as a comforting, predictable reservoir of growth and renewal at a time when the natural environment was becoming increasingly remote.

Fritz Baer. Sommertag, Weiden am Bach (Summer Day, Willows on Brook), ca. 1905. Oil on linen. 37 5/8 x 47 3/4 in. Founding Collection, Gift of Charles and Emma Frye, 1952.002

Carola Baer-von Mathes. Herbstwald mit Kühen (Autumn Forest with Cows), ca. 1890. Oil on linen. 26 7/8 x 34 1/2 in. Founding Collection, Gift of Charles and Emma Frye, 1952.003

Arnold Gorter gained international renown for his paintings of the Dutch landscape. His calm scenes feature low horizon lines that emphasize the flatness of the land; when livestock and humans are included, they are typically embedded in the landscape itself. In Autumn Sun, the cows are aligned with the ruts in the damp ground. In this way, Gorter combines domesticated animals with evidence of human impact on the land to create a unified scene in which land, humans, and livestock seem to maintain a peaceful coexistence.

Installation view: Jueqian Fang

Animal as Subject

In the paintings in this section, animals no longer merge with the landscape; they instead appear as assertive, worthy subjects in their own right. For much of the history of Western painting, animals were regarded as inferior to humans as subjects for painting, often appearing as staffage—a term for the small figures that punctuate landscapes. However, as older, hierarchical political and religious orders were replaced by democratizing movements throughout the nineteenth century, formerly “unimportant” subjects acquired artistic acceptance and widespread popularity. Animal imagery became especially popular as more people, particularly city dwellers, had fewer opportunities to interact directly and consistently with animals. Artists responded to this interest, and animal painting flourished as a genre.

Animal paintings by prominent artists from the nineteenth and twentieth centuries make up a significant portion of the works collected by Charles and Emma Frye. There is a notable focus on German animal painters—particularly Anton Braith, Johann Friedrich Voltz, and Heinrich von Zügel. Over the course of their careers, these three artists helped elevate representations of animals to new heights through careful study and innovative techniques. Their contributions to the artistic environment in Munich helped make it the dynamic center of cultural creativity in the German-speaking realm during this period.

Gabriel von Max. Botaniker (The Botanists), ca. 1900-1915. Oil on canvas. 25 x 31 3/4 in. Founding Collection, Gift of Charles and Emma Frye, 1952.117. Photo Credit: Eduardo Calderón

Gabriel von Max was friends with Ernst Haeckel, a prominent popularizer of Darwinian theories in Germany, including the argument that humans and apes had a common ancestry. Max was fond of monkeys, and he lived with several as companions. In his paintings, he frequently portrayed them engaging in research that mirrored his own interests in natural history. In Botaniker, Max depicts a group of monkeys investigating the flowers of an overturned bouquet with great concentration.

Despite the ingredients of this scene, Max avoids the well-established tradition of presenting simian models “aping” human behavior in order to make humorous or moralizing statements. Instead, the artist takes the monkeys’ investigations seriously, portraying them as creatures who—like humans—are curious, social, and willing to participate in collaborative inquiry.

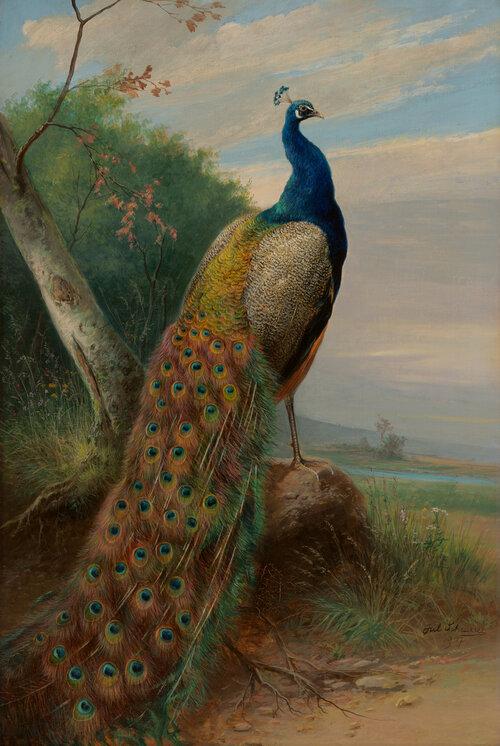

Julius Scheuerer. Peacock, 1907. Oil on canvas. 36 1/2 x 24 1/2 in. Founding Collection, Gift of Charles and Emma Frye, 1952.148. Photo: Jueqian Fang

Julius Scheuerer was an animal painter who specialized in pictures of poultry and other small livestock in farmyard settings. Although peafowl have long been raised by humans, in this painting Scheuerer portrays a peacock without any sign of domestication. In the absence of human presence, the bird dominates the landscape.

Ludwig Knaus. Drove of Swine: Evening Effect, 1878. Oil on canvas. 19 5/8 x 14 3/8 in. Founding Collection, Gift of Charles and Emma Frye, 1952.085. Photo: Jueqian Fang

Walter B. Douglas. Rooster and Chickens, ca. 1920. Oil on canvas. 16 x 20 in. Founding Collection, Gift of Charles and Emma Frye, 1952.038

Alexander Max Koester. Ducks in Green Water, ca. 1910–13. Oil on canvas. 25 x 38 in. Founding Collection, Gift of Charles and Emma Frye, 1952.088. Photo: Jueqian Fang

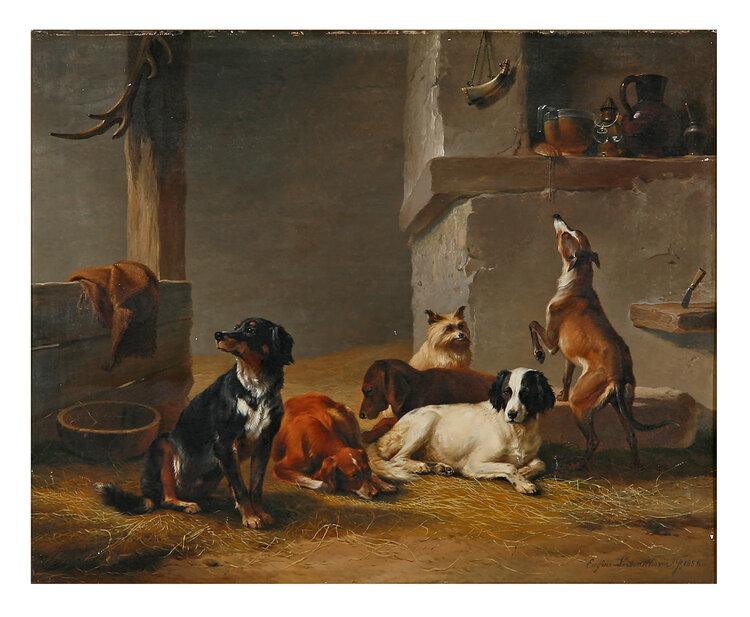

Eugène-Joseph Verboeckhoven specialized in animal subjects, primarily focusing on domesticated animals. In this painting, he carefully individualizes each dog, attending to their breed-specific features and qualities. He highlights the hound’s elongated profile, the setter’s restless attentiveness to something beyond the frame, and the terrier’s stare directed toward something that none of the others seems to notice. The straw-strewn setting also indicates their status as working dogs rather than house pets.

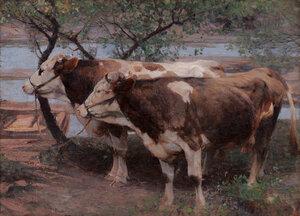

In contrast to many of his contemporaries, Johann Friedrich Voltz devoted careful attention to faithfully re-creating the specific details of his animal subjects’ individual features and surroundings, emphasizing their figures rather than their movements or their interactions with other living beings. His focus encourages careful observation of each animal’s distinctive form, colors, and textures. In this way, he not only demonstrates that he respects animals enough to observe them closely and portray them sensitively, but also pays homage to Dutch artist Paulus Potter’s The Bull (1647), a monumentally scaled painting that inspired Voltz and many other nineteenth-century European painters to specialize in animal subjects.

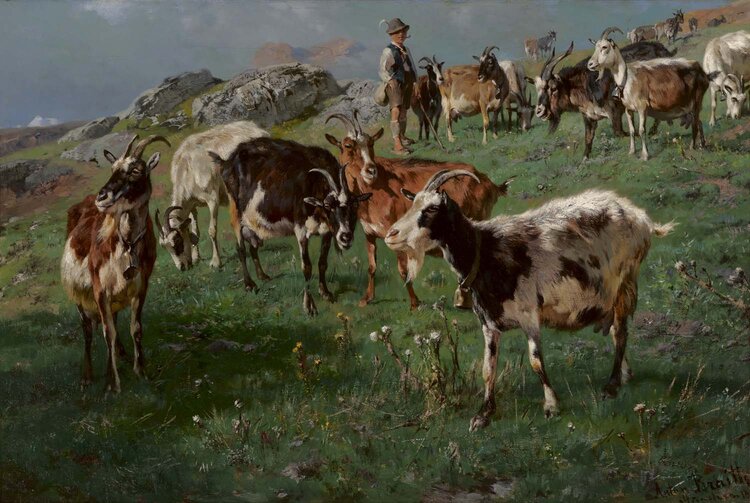

Anton Braith. Goats and Sheep, ca. 1870.

Oil on linen. 11 5/16 x 18 5/8 in. Founding Collection, Gift of Charles and Emma Frye, 1952.016. Photo: Jueqian Fang

As the son of a farm manager, Anton Braith began working with livestock as a child. This experience enabled him to observe firsthand the types of relationships between humans and livestock that were part of everyday rural life in nineteenth-century Europe. In Goats and Sheep, he portrays this life as peaceful and dependable, with the resting animals and the people who tend them illuminated against a backdrop of storm clouds. This idealized vision presents an alternative to the hectic, unpredictable, and increasingly machine-driven pace of life in the modern city, where many collectors of animal paintings lived.

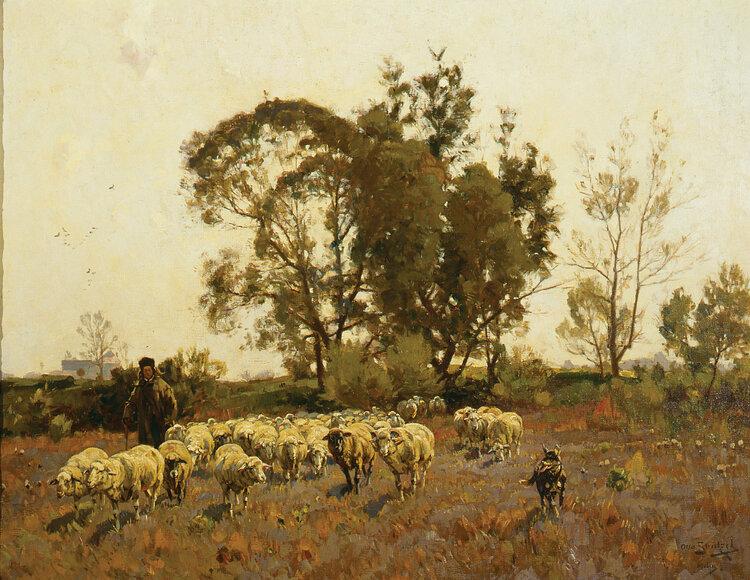

Heinrich von Zügel frequently depicted domesticated animals together with farmers, shepherds, or herders. However, his later works drew attention to animals’ sense of agency, downplaying their control by humans. In Schafherde mit Hirte, Zügel focuses on the sheep rather than the shepherd. Much of the flock appears to be an undifferentiated mass, but the faces of the sheep in the foreground are individualized. By contrast, the shepherd’s face is indistinct, a featureless mass of brushstrokes. The sheep in front surge forward energetically, eager to move out of their confining enclosure, and the group separates into distinct bodies. The shepherd who opens the gate for them seems to be present primarily to attend to their wishes.

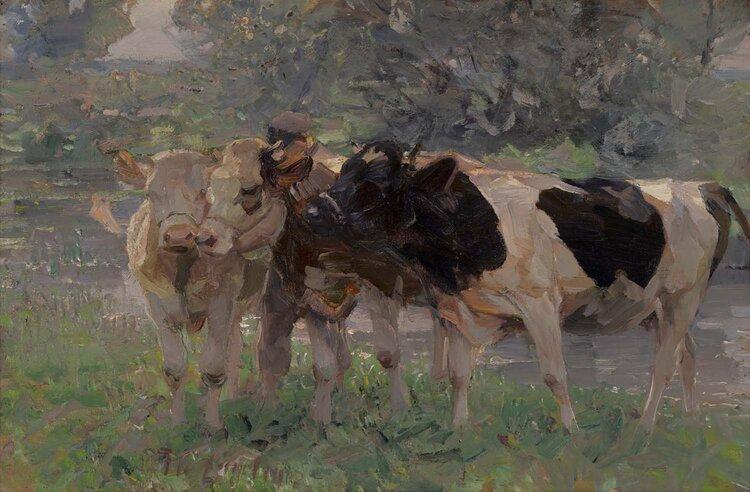

In this painting, Heinrich von Zügel emphasizes interspecies bonds through his treatment of color, light, and composition. He unites cows and their drover (a driver of cattle or sheep) through a distribution of color that intermingles human and bovine bodies to such a degree that the drover’s and cows’ legs are nearly indistinguishable from one another.

Heinrich von Zügel. Old Man Asleep with Sheep, 1870s. Oil on canvas. 21 1/2 x 28 1/4 in. Founding Collection, Gift of Charles and Emma Frye, 1952.209. Photo: Jueqian Fang

Installation view: Jueqian Fang

Animal Labor

Working animals frequently appear in animal paintings. In this gallery, they are shown performing their tasks: oxen pull heavy carts and plows; horses draw carriages; dogs herd sheep and cattle. But often, the labor that animals undertake for us is not easily identifiable: cows produce milk, sheep yield wool, and chickens lay eggs. These animals “work” as they live and involuntarily prepare their bodies for death: when they reach a certain age and weight, they are slaughtered, their hides become leather, and their bodies are butchered into cuts of meat.

This less obvious type of animal labor also underlies Charles and Emma Frye’s art collection. Their wealth came primarily from Charles’s meatpacking business, and they collected many paintings of cattle, sheep, and other farm animals “at work” in pastures and farmyards. These scenes present farm animals’ workplaces as sites of safe, harmonious cooperation among various animals, and between humans and animals. Such idyllic portrayals focus on animals as living beings rather than as sources of profitable products. They also elide the reality that farm animals are destined for slaughter and consumption, presenting scenarios in which peaceful coexistence appears as a viable, desirable option.

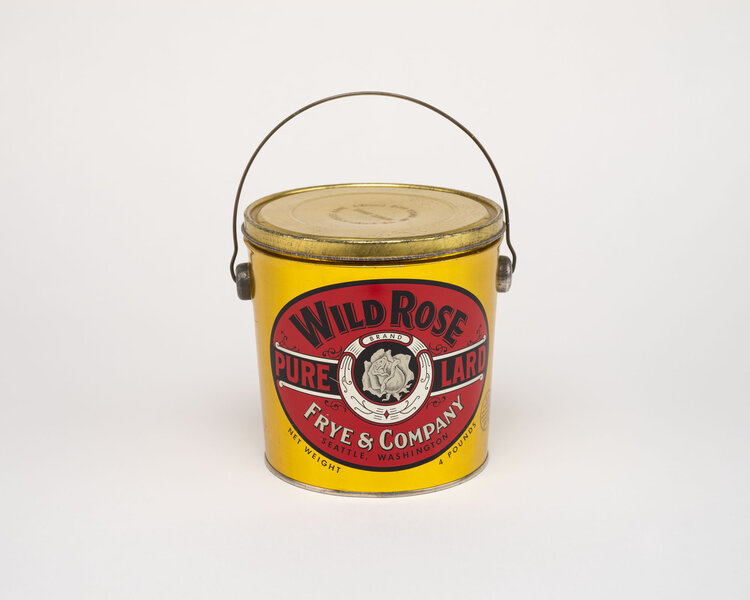

However, the archival materials from the Fryes’ businesses, such as the can of the Frye brand Wild Rose lard, demonstrate that the actual value of livestock to humans is determined by the profitability of what such animals “produce”—mutton, beef, hams, bacon, tallow, leather, lard. The art collection financed by this “work” of livestock is proudly featured in a 1945 publicity brochure for the modernized Frye meat processing plant, which pairs a photograph titled “Killing Floor Scenes” with an image of employees posed in front of some of the Fryes’ art collection.

Charles Edward Johnson. Dipping Sheep, 1890. Oil on canvas. 40 1/4 x 60 in. Founding Collection, Gift of Charles and Emma Frye, 1952.075

To combat parasites that can severely damage the health of their flocks, farmers bathe their sheep in chemicals with insecticidal and fungicidal properties. Commercial sheep dips became available in the 1830s; the earliest type used arsenic as its base. Dipping sheep not only helped maintain the animals’ health; it also ensured their continued productivity—their capacity to yield high-quality wool and meat.

Charles Edward Johnson depicts a scene in which dipped sheep are being rinsed in a stream that runs through a village—a use of natural waterways that was typical of the time. Yet the idyllic scene elides the negative consequences of this practice. The environmental damage was significant, and the use of streams and ponds in the dipping process declined in the face of regulations designed to protect human and environmental health.

Ludwig Willroider. Landscape with Oxen, ca. 1880. Oil on canvas. 25 3/8 x 34 1/4 in. Founding Collection, Gift of Charles and Emma Frye, 1952.197

Anton Braith. Shepherd with Goats, 1895. Oil on canvas. 19 13/16 x 31 in. Founding Collection, Gift of Charles and Emma Frye, 1952.015. Photo: Jueqian Fang

Otto Strützel. Autumn Morning with Sheep, n.d. Oil on linen 27 3/4 x 35 1/2 in. Founding Collection, Gift of Charles and Emma Frye, 1952.162

The landscape and animal painter Otto Strützel caught the attention of the prominent animal painter Heinrich von Zügel, who invited the younger artist to study with him. In Autumn Morning with Sheep, Strützel, like Zügel, emphasizes the positive, cooperative relationships between humans and domesticated animals. Working together, a shepherd and a dog flank a flock of sheep, monitoring them as they all move across a field dotted with drying foliage that reflects the season. The sheep appear comfortable with their companions; several lag behind the rest, while others begin to move ahead, leading the way. The dog appears more attentive to these movements than the shepherd—it seems to exchange looks with one of the lead sheep, as if to remind it not to stray too far.

Henry Raschen. Landscape with Campfire, ca. 1915–20. Oil on canvas. 36 1/4 x 57 3/8 in. Founding Collection, Gift of Charles and Emma Frye, 1952.136. Photo: Jueqian Fang

Christian Speyer. Four in Hand, 1911. Oil on canvas. 35 9/16 x 57 5/16 in. Founding Collection, Gift of Charles and Emma Frye, 1952.159

Eustace Paul Ziegler. Packhorses at Mt. Rainier, n.d. Oil on canvas. 26 x 34 in. Bequest of Hugh S. Ferguson, 2011.006.02. Photo: Spike Mafford

Eustace Paul Ziegler frequently painted scenes of mountainous terrain in and near the Pacific Northwest, particularly around Denali in Alaska and Mount Rainier in Washington—backdrops against which he presents hunters, prospectors, and their packhorses. By doing so, Ziegler highlights the important role that animals, especially horses, played in the exploration of the Pacific Northwest by white settlers during the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries.

In this painting, a group of horses stands idly on a promontory as one stares out over the precipice. No humans appear, yet their presence infuses the scene. The horses do not seem to be fully at rest. Instead, they appear poised to resume their work after a brief break—they still wear blankets and harnesses, indicating that they can expect to be saddled or loaded very soon so they can continue to transport riders and supplies across the challenging landscape.

Ziegler, a prominent figure in the early Seattle arts scene, was a close acquaintance of Charles and Emma Frye, and while the Fryes did not collect Ziegler’s work, the first two directors of the Museum, Walser and Ida Kay Greathouse, avidly acquired Ziegler’s work for the collection.

John Califano. Pointers in the Woods, Autumn, ca. 1905. Oil on canvas. 40 5/8 x 61 3/4 in. Founding Collection, Gift of Charles and Emma Frye, 1952.020

Pointers—the species of dog depicted in this work—are classified as gun dogs, which are bred and trained to assist hunters. A gun dog’s task is to scent the hunter’s prey, usually game fowl; when it locates a bird, it communicates the location by freezing in a crouching or pointing position before flushing the bird, if necessary, into the range of a hunter’s shot.

John Califano portrays his pointers in the process of locating birds. The dogs appear as small yet active central figures set in a large autumnal landscape. They seek the scent of prey in the air, each concentrating on a different area, while a tiny hunter stands at a considerable distance.

Percival Rosseau. Two Gordon Setters in a Field, 1904. Oil on canvas. 23 3/4 x 32 1/4 in. Founding Collection, Gift of Charles and Emma Frye, 1952.146. Photo: Jueqian Fang

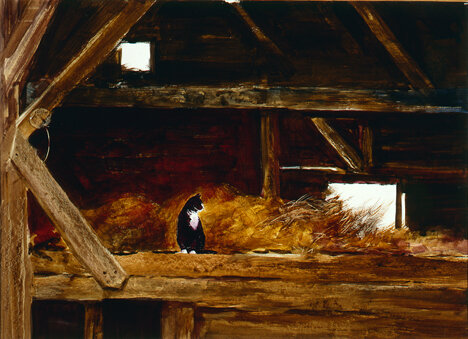

John Pellew. Barn Cat, ca. 1983. Watercolor on paper. 20 1/2 x 28 1/2 in. Museum Purchase, 1983.012

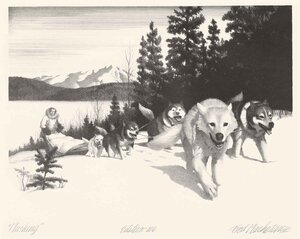

Fred Machetanz. Mushing, 1963. Lithograph. 17 x 20 7/8 in. Museum Purchase, 1995.001.28. Photo: Jueqian Fang

Fred Machetanz. Coffee Break, 1972. Lithograph 18 x 22 1/2 in. Museum Purchase, 1995.001.43. Photo: Jueqian Fang

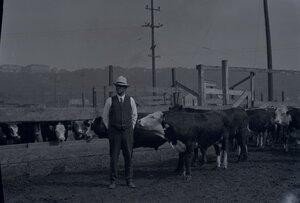

From left to right: Poplar Livestock Company, Montana, 1920s; Frye-Bruhn meatpacking plant, Seattle, 1897; Frye-Bruhn market, 1920s. Frye Art Museum Archives

Charles Frye settled in Seattle in 1888, along with his wife, Emma, and his brother Frank. Together the brothers opened several meat markets in the city, and in 1891 they formed a meatpacking business with their friend Charles Bruhn. During the brief Klondike gold rush that began in 1897, the business thrived. Prospectors needed supplies, including preserved meat, to sustain them on the grueling journey through Alaska to the gold fields in the Canadian Yukon territory, so the Fryes and Bruhn opened markets in Alaska. While the core of the business would always remain in Seattle, Charles Frye continually sought out new business ventures near and far, becoming the sole owner of the company in 1910. During the 1920s and 30s, he acquired and leased large swaths of land in eastern Montana for cattle grazing and other agricultural developments.

From left: Frye-Bruhn market, Seward, Alaska, late 1880s–1920s; Frye-Bruhn market, Juneau, Alaska, 1925. Photo: Elite Studio. Frye Art Museum Archives

Early twentieth-century photographs of the Frye-Bruhn meat markets emphasize the modern cleanliness and orderliness of the well-stocked interiors, where fresh and preserved meat products are displayed without reference to the living animals who have been converted into purchasable items. Strikingly, the photograph of the storefront in the “frontier” environment of Seward, Alaska, presents a distinct contrast between the sanitary, “civilized” products inside the store, evident in the neatly plucked and decapitated fowl hanging behind the clean front windows, and the once-living wild animals outside the store, as seen in the moose skulls and furs arranged on the porch.

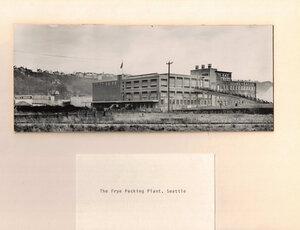

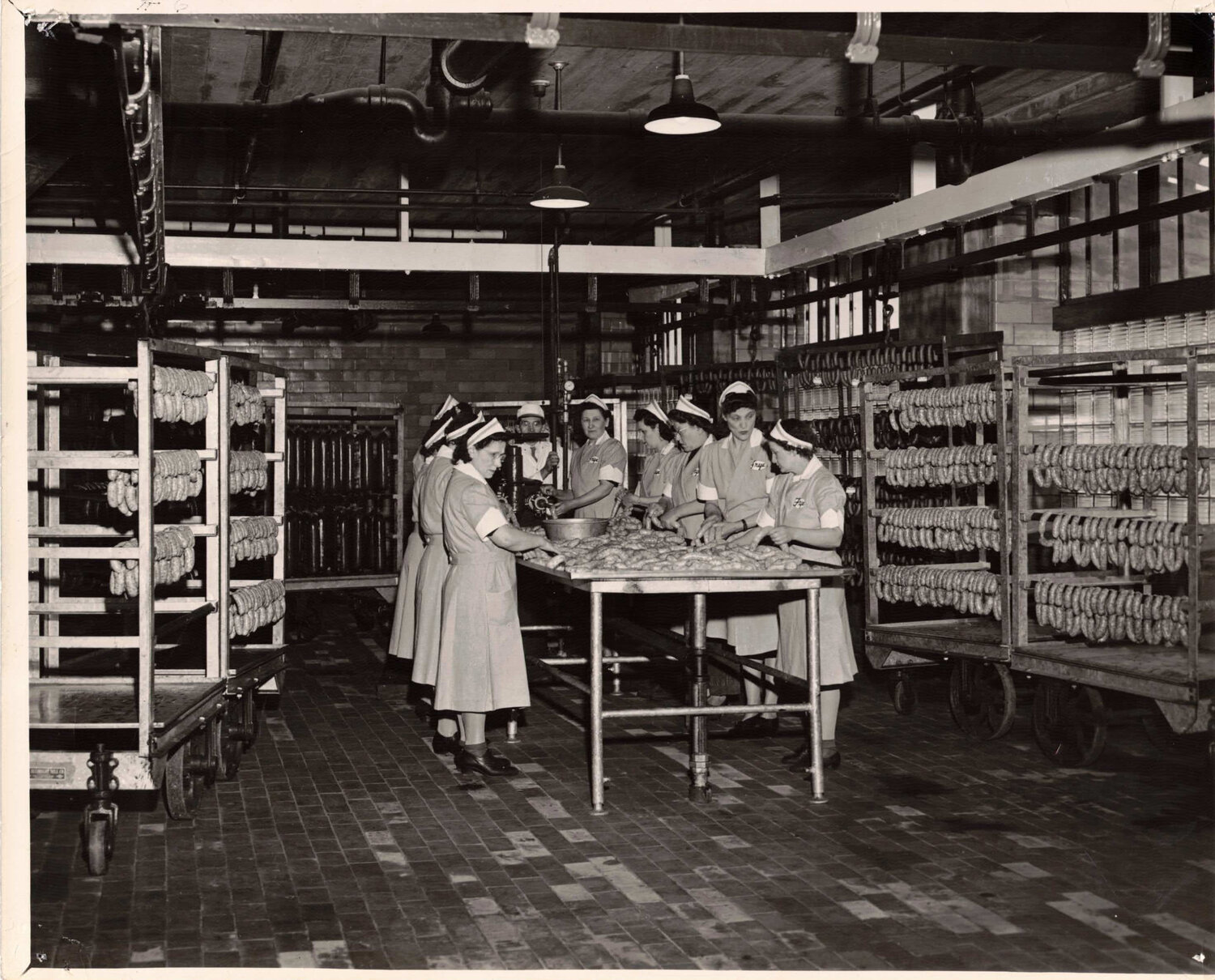

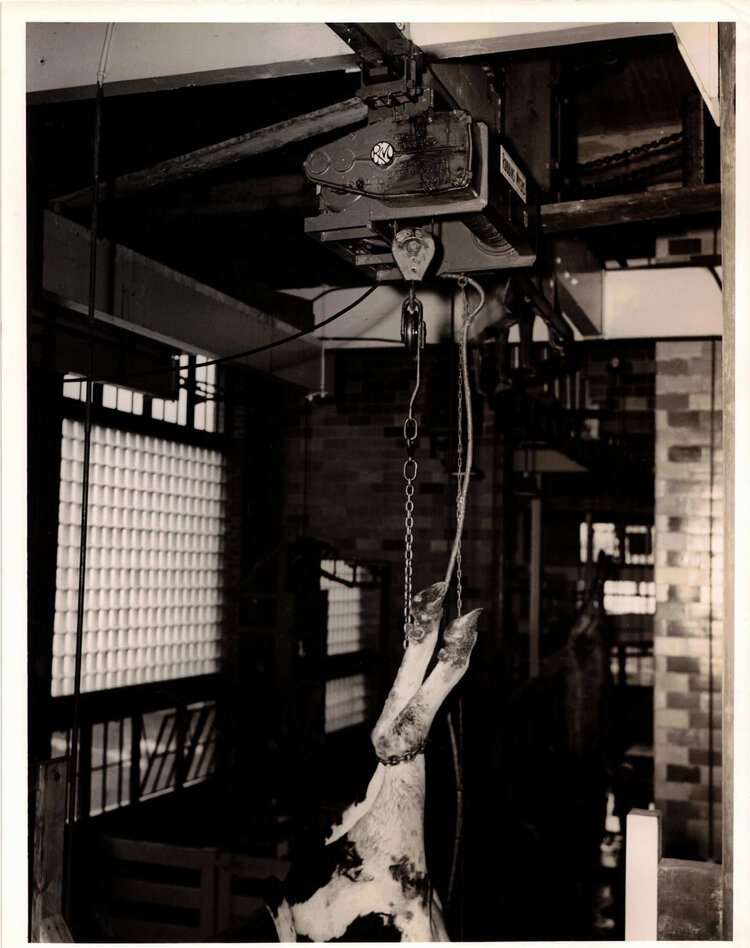

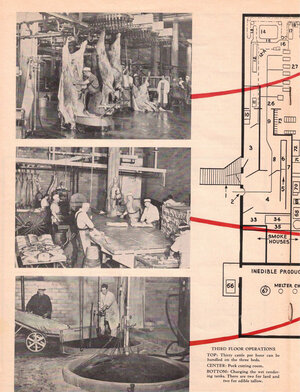

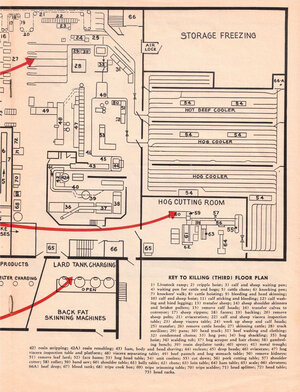

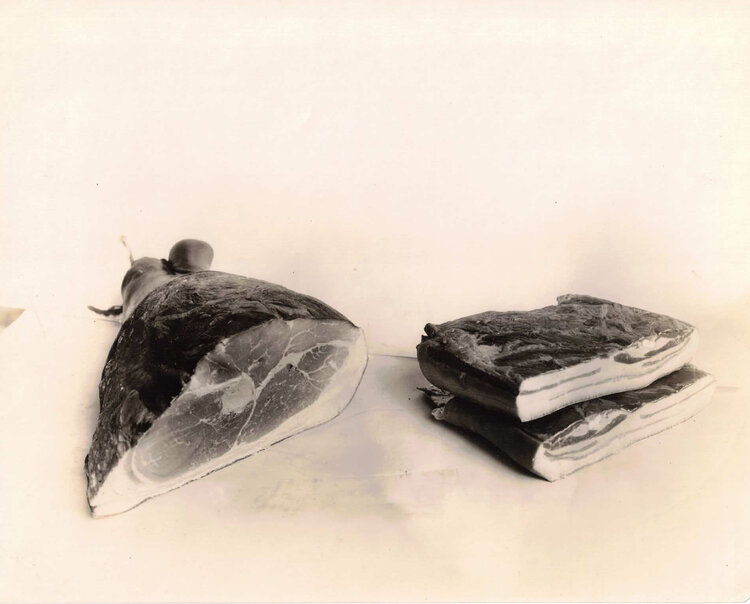

Meatpacking operations, Frye & Company, ca. 1945. Frye Art Museum Archives

Meatpacking operations, Frye & Company, ca. 1945. Frye Art Museum Archives

Meatpacking operations, Frye & Company, ca. 1945. Frye Art Museum Archives

Publicity brochure, Handling Cut to a Minimum in Frye’s Modern Plant, pages 2–7, 1945. Frye Art Museum Archives

In February 1943, a prototype of Boeing’s B-29 bomber—the plane that the US would use in 1945 to drop nuclear bombs on Japan, killing thousands of people instantly—crashed into the Frye meatpacking plant, killing a firefighter, twenty of the plant’s employees, approximately eighty hogs, and the entire flight crew. The fires that ensued destroyed the plant, requiring it to be rebuilt. The new meatpacking operations were designed to take advantage of the most recent technologies and practices.

A publicity brochure for the new plant, which opened in 1945, describes the steps a live animal passes through as it becomes meat and the mechanized equipment used to facilitate that process. It highlights the industrial efficiency with which, during each hour of operation, hundreds of animals were stunned, killed, bled, skinned, dismembered, and, in many cases, ground up, boiled, steamed, or smoked, before being packaged and shipped out for sale.

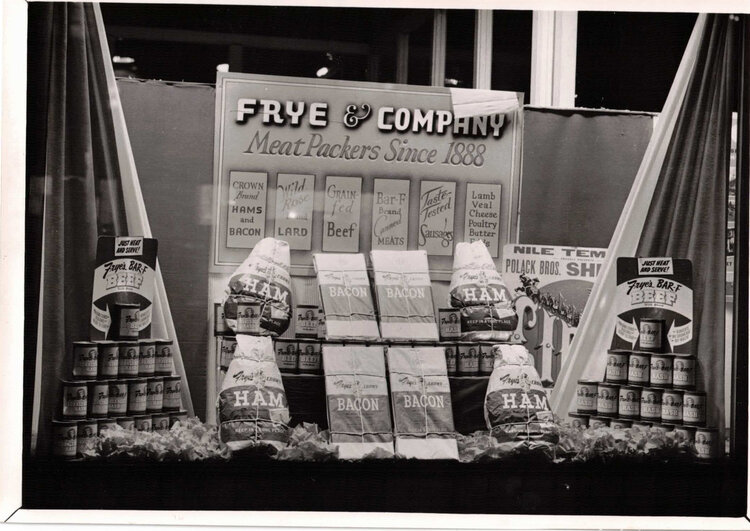

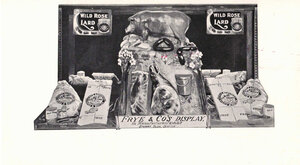

Frye & Company product display, Seattle, 1910–1950. Photo: Seattle Post Intelligencer. Frye Art Museum Archives

Frye & Company "Wild Rose” lard can, 1910–1950. Frye Art Museum Archives

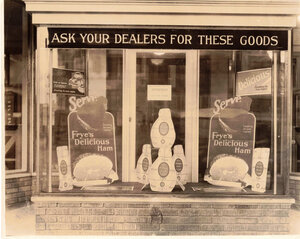

From left: Frye postcard advertisement, 1910–1950; Frye-owned market window display, Yakima, WA, 1910–1950. Frye Art Museum Archives

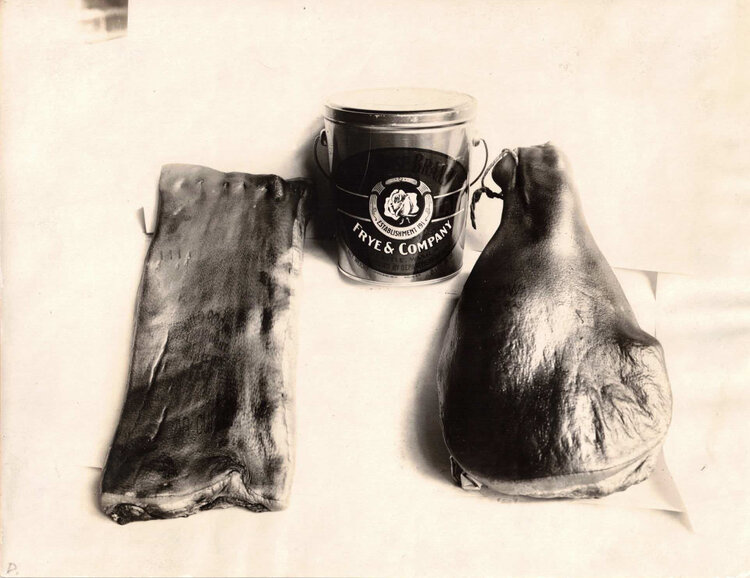

Photographs of the hams, lard, bacon, and other processed meat products manufactured at the Frye plant were useful for advertising. These pictures did not simply present the commodities that animals’ bodies had become; the photographic process itself also depended on animals.

The most common chemical process used for creating black-and-white photographic prints during the late nineteenth and twentieth centuries required gelatin—an animal product made from the collagen yielded by heating the skin, bones, tendons, and ligaments from slaughtered livestock. Gelatin, combined with light-sensitive silver salts, was used to coat the papers on which photographic negatives were printed, in what is known as the gelatin silver process.

These photographs also call to mind two meanings of the word “render”: to produce a copy and to extract by melting. As a product, the can of Frye’s Wild Rose lard encompasses both meanings. Lard is the result of rendering (extracting and melting down) fat from pigs’ bodies. And the profitable sales of lard and other processed meat products provided the Fryes with the means to acquire their art collection, which includes renderings, or likenesses, of the types of domesticated animals that had become meat.

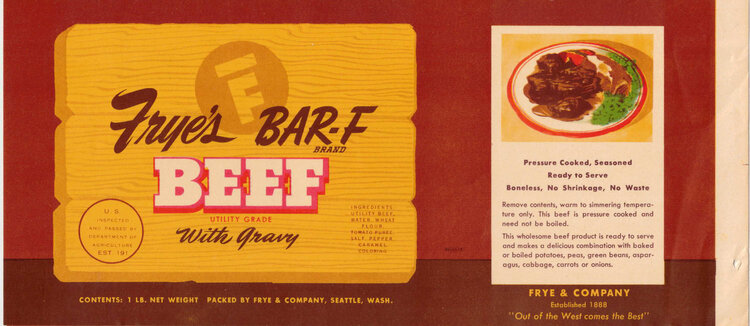

“Frye’s BAR-F Brand Beef” product label, 1910–1950. Frye Art Museum Archives

Frye & Company products, Seattle, ca.1911–1920. Photo: Curtis & Miller Frye Art Museum Archives

Frye & Company products, Seattle, ca. 1911–1920. Photo: Curtis & Miller. Frye Art Museum Archives

Installation view: Jueqian Fang

Animal Culture

Humans were able to develop complex societies by controlling nature, tilling the land to cultivate crops and domesticating animals to adapt them for human use. These efforts ensured reliable access to nutrition, thereby granting humans the strength and time to also develop their expressive capacities—to cultivate culture. As we humans have become more “civilized,” we have become increasingly distant from nature, including our own status as animals. We have convinced ourselves that culture is exclusively human, regardless of the fact that its development would not have been possible without nature’s plants, animals, and soil.

In art, however, we can find reminders that animals have contributed to culture and that, in fact, they actively participate in it. As the paintings in this section reveal, although humans have long believed that our capacity for language and abstract reasoning separates us from our fellow creatures, animals can also understand deep emotions and complex ideas, which they can communicate to others, including us. These works depict cows who decode human movements to recognize the daily routines they share with shepherds, sheep who stand out as independent individuals even as they remain part of the larger flock, and domesticated animals and humans who have forged close interspecies bonds that allow them to agree upon how they divide up space, or how and where they move. These paintings encourage us to consider animals’ capacity to make meaning, their ability to cooperate with us and other animals, and their capability to think through their own decisions. These artworks help us recognize that animals’ cultural competence makes them an integral part of what we tend to think of as the human world.

Léon Barillot. Three Cows and a Calf, ca. 1890. Oil on linen. 52 x 64 1/4 in. Founding Collection, Gift of Charles and Emma Frye, 1952.005. Photo: Jueqian Fang

Léon Barillot’s paintings present cows as individual thinking beings, highlighting their awareness of one another and other species, including humans, along with the modes of communication they use to establish and maintain those connections.

If this scene is read as depicting the end of the cows’ active working day, the cows, sheep, and shepherd can be seen as coworkers, all operating according to the same schedule and cooperating as they complete their “shift.” As a flock of sheep and shepherd move toward them, the cows watch attentively, seeming to have expected their appearance; upon their approach, the cows know it is time to return to the farmyard to be milked and to rest for the night. The calf in the foreground directs its gaze at the viewer, underscoring the animals’ awareness of humans and the meaningful exchanges that can arise between them.

Léon Barillot. Cattle, ca. 1880. Oil on linen. 21 7/16 x 28 13/16 in. Founding Collection, Gift of Charles and Emma Frye, 1952.007

Emile van Marcke de Lummen. In the Marshes, ca. 1880. Oil on canvas. 42 1/2 x 63 in. Founding Collection, Gift of Charles and Emma Frye, 1952.178. Photo: Jueqian Fang

Carl Ebert. By the Shores of Chiemsee, 1880. Oil on canvas. 24 3/8 x 40 1/2 in. Founding Collection, Gift of Charles and Emma Frye, 1952.041. Photo: Spike Mafford

Carl Ebert’s By the Shores of Chiemsee provides a glimpse of the type of interspecies communication and cooperation that can develop among domesticated animals. In this painting, cattle and sheep move together along a path, unguided by the human herder behind them, yet seemingly in agreement about their direction and pace. Ebert’s depiction of the herder not as the dominant figure but as an equal presents an idealizing vision of a multispecies community that can be nonhierarchical, mutually beneficial, and functional.

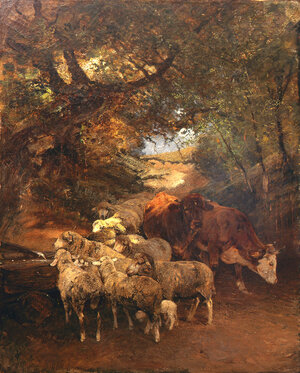

Heinrich von Zügel. Herd of Sheep and Cattle at a Well in a Wooded Narrow Pass, Brixlegg, ca. 1880. Oil on canvas. 29 1/2 x 23 1/2 in. Founding Collection, Gift of Charles and Emma Frye, 1952.204

Adolphe Charles Marais. Peasant Girl with Cattle, 1890. Oil on canvas. 41 3/4 x 53 1/4 in. Founding Collection, Gift of Charles and Emma Frye, 1952.110. Photo: Jueqian Fang

Paul Weber. Shepherd with his Flock, ca. 1880. Oil on canvas. 24 x 42 3/8 in. Founding Collection, Gift of Charles and Emma Frye, 1952.186

In this painting, Paul Weber subtly depicts the coordinated efforts of shepherds and herding dogs, which rely on nonverbal communication and a shared understanding of sheep, dog, and human behaviors. A shepherd and dog guide a flock of sheep and lambs through a field. The shepherd monitors the animals, and on the opposite side of the flock, the dog turns its head, seeming to check for stragglers and perhaps even preparing to exchange looks with the shepherd as it strategizes how best to continue guiding and protecting the sheep.