Curator of Marsden Hartley: An American Nature Georgia Erger (left) and Katherine Bradford (right). Photo: Jueqian Fang

Katherine Bradford is vocal about the impact the work of Marsden Hartley (1877–1943) has had on her artistic development. In addition to a geographic bond, the two artists share a stylistic ethos—to evoke a maximum of sentiment with minimum detail, resulting in a deceptive simplicity that Bradford affirms as ‘unfussy.’ At the Frye, we often place contemporary artists in dialogue with historical predecessors, a practice that is animated by our commitment to revisit and refresh the scholarly record of our own collection. Two current exhibitions, Flying Woman: The Paintings of Katherine Bradford (on view at the Frye February 4–May 14, 2023) and Marsden Hartley: An American Nature (February 11–May 21, 2023) offer an example of one such rich cross-historical relationship.

It is not simple kismet that An American Nature is on view simultaneously with Bradford’s solo presentation. Keying off the importance of Hartley’s influence on Bradford, our curatorial staff looked to the museum’s own collection to consider how the conversation between the two artists could be brought to life in the galleries. An American Nature is built around two paintings in the Frye’s collection, acquired in the 1950s as the museum’s inaugural directors strove to contextualize the Founding Collection of European modernism with American modernism—a genre that for many is iconically represented by Hartley’s distinctive body of work.

Born in Lewiston, Maine, Hartley’s artistic ambitions drew him all around the globe. It wasn't until 1937—just six years before his death—that Harley returned permanently to New England, declaring himself “the painter from Maine,” a purposeful designation that decisively shaped his legacy. Katherine Bradford moved to Maine in the 1970s, and the close-knit community became an important incubator for her artistic career. Though she has long lived between New York City and Maine, the latter location remains central to her identity.

Upon the opening of the dual exhibitions, we invited Katherine Bradford to speak about her personal connection to Hartley in the gallery of An American Nature. The following is a transcript of her talk, edited for clarity.

When I was struggling to realize myself as a painter in the 1970s, I was living in Maine. Marsden Hartley was born in Maine and he decided, like many of us, he wanted to leave home and see the wider world. He went to Europe, he showed in New York...but then came back to Maine at the end of his life. And those of us in the art world in Maine—this hit us hard, that this marvelous painter wanted to be known as “the painter from Maine.”

Many of us revered him, and I was definitely one, because he was doing what I wanted to do. You notice that all his scenes are recognizable but they’re not “realistic.” I wouldn’t say he’s painting from memory; I think that’s a tricky word. I think he invented things, like the clouds. Yes, those are two clouds, but you’ve never really seen a cloud that looks like that. I call them Marsden Hartley clouds. And that really hit me—you can invent a way, your own way, of doing a foot, a cloud, or anything...

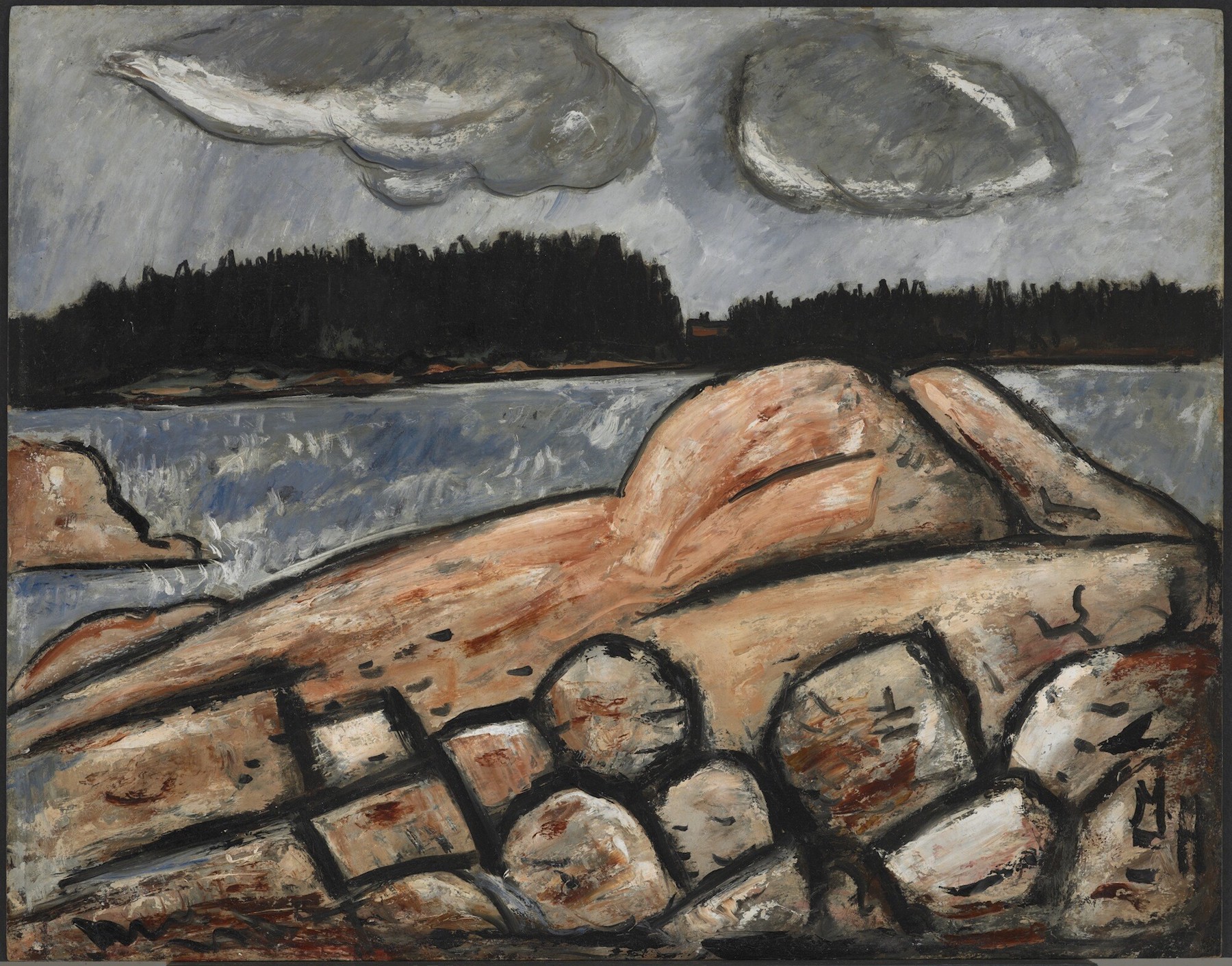

Marsden Hartley. After the Storm, Vinalhaven, 1938–39. Oil on Academy board. 22 x 28 in. Bowdoin College Museum of Art, Brunswick, Maine, Gift of Mrs. Charles Phillip Kuntz, 1950.8. Photography by Peter Siegal

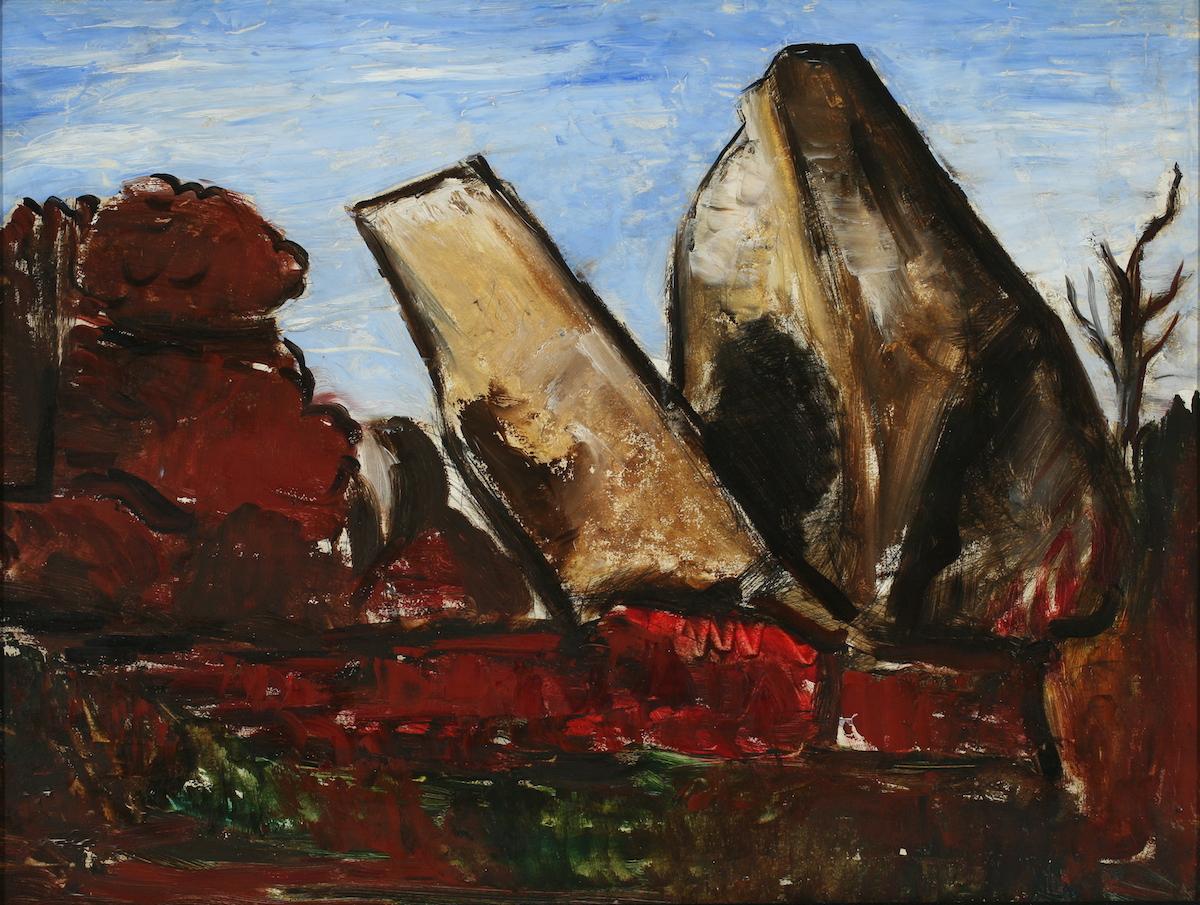

He wasn’t in his lifetime that successful, and that was very encouraging to me. He was a queer man who at the time could not be openly queer. I was on the way to coming out myself. That was tremendously moving to me, that he had to be very private about who he was. And most of all, it was the way he painted which was very direct. He wasn’t fussy about anything. Think about if you’re painting two big rocks [as in Whale's Jaw, Dogtown Common, Cape Ann, Massachusetts], how you could try to get all the details in—but he didn’t. He gave you the general idea, and I think it’s very convincing. And the black outlines, I certainly took advantage of, as I saw Philip Guston do the same thing, and many other artists.

Although I wasn’t at art school as a young painter, I did have the great joy of looking at really good paintings, because this painting right here [After the Storm, Vinalhaven] I could drive by every day on the way to the grocery store. This belongs to the Bowdoin College Museum of Art, which is down the road from where I was living. They made a poster of it, which I hung above my bed. And when I saw that hanging here [at the Frye], I was just home. It’s such a great painting. This is the coast of Maine; this is the way it feels. But again, he gave you the impression of its hard rock, the rocky coast. He wanted to give you a feeling.

The feeling of a wave crashing against the rocks...You go through many museums and you’ll encounter many painters who wanted to do waves—it was a favorite subject, the transparency especially. How did they paint a crashing wave with light shining through it? Not sitting there on the beach, looking at waves. But I like what Hartley came up with. He was going to give you the feeling of that wonderful white spray when it breaks.

Feeling. I thought he was full of feeling.

Bradford is also currently participating in an exhibition at the Bates College Museum of Art in Lewiston, Maine, And So Did Pleasure Take the Hand of Sorrow..., which features the work of eight contemporary artists whose work engages with Hartley. The exhibition is on view through March 18, 2023.